There’s a tiny technical glitch underpinning the legal integrity of Medicare auditing that could one day blow up the whole system.

This is a tale of two problems with Medicare. One is plainly visible, and looms like a dark tower over working GPs, while the other is like a well-hidden parcel of dynamite.

Medicare audit anxiety is a real thing that affects most doctors who provide (bulk-billed) “free care” to their patients.

Medicare rules keep changing with little notice or clarity.

Should the Medicare cops come knocking on their door, we know now that there is virtually nothing a GP can do about it but humbly pay it all back and wear any humiliation that accompanies the government default notice on their use of MBS items.

The way the current system works has been described as like getting a speeding ticket from a hidden camera when nobody will tell you the speed limit until you get caught. (Yes, strap in for a multi-metaphor ride.)

Once you do get “caught” you have to pay back two years’ worth of speeding fines based on your gross income. It does not matter if you were actually in the car speeding.

According to two surveys, it looks like a large proportion of doctors are withholding services either regularly or from time to time for fear of a Medicare audit.

In Healthed/The Medical Republic’s recent landmark national GP survey of more than 1,400 doctors conducted just a few weeks ago, it was found that over 84% of GPs, regularly, or from time to time, don’t perform certain services because of anxiety over the PSR.

But “Medicare audit anxiety” is not a recent phenomenon. The fear effects of Medicare audits on doctors’ practising behaviour can be traced back as far as the mid-1990s.

Back then I helped establish a women’s health clinic for a client (at a time where male doctors dominated the workforce). Within 12 months of the clinic’s commencement, the only dedicated female doctor clinic received a Medicare audit letter for “performing too many Pap smears”.

Driving without road rules

What’s the main reason for the anxiety? It’s not knowing when you’re doing the “wrong” thing.

Assume you are a good, ethical doctor. After many years of study and work, you have just set yourself up in a hard-earnt, brand-new, state-of-the-art practice.

You deserve it! Your patients and friends are impressed with your commitment. Everybody is cheering you on, including your suppliers and the government!

To help pay for your high-quality practice, you decide you want to make your services (bulk-billed) free to the patient.

The government loves your choice. The punters (voters) and politicians love it.

For the long hours you put in, while fighting a tsunami of problems while your income goes backwards, you should be in line for a citizen’s award for your free services to humanity.

Unfortunately for you (the good doctor), you have taken up driving and no one has provided you with any road rules.

When you work this out, all you want to know is one simple thing: is going over 130km/h going to get you into trouble with the police?

The problem is that, for three decades, nobody has been prepared to write a book of rules, so nothing is really clear. You have to do some guessing and assuming of what you think people want.

The federal government admitted in Parliament 10 years ago that there is no commonly peer-reviewed, agreed-upon detailed driver education or published (clinically relevant) standards by which you can guide your practice of billing.

No standards on how to drive safely or what the speed limit is!

Worse, there is no appetite or urgency to give answers when people’s lives are at risk. The government, their professional drivers’ association and the law firmly state it is not their job to interpret or even set the speed limit. They collectively state it is up to you to interpret with your peers.

For decades, fellow drivers have been given the same government run-around on the phone.

They get a different answer every time they ring. In the end, you get an answer in writing. After the pleasant exchanges on an official government letterhead, they say we cannot tell you the speed limit, ask your friends.

In the meantime, you naively ask your trusted makeshift peer review group on social media. After all, they appear to be your more knowledgeable and experienced driving buddies. You even attend an ‘expert’ seminar on the road rules put on by someone who has spent quite a bit of time interpreting what they think the rules are and how you can apply them.

With good intentions but questionable authority, they tell you of their war stories.

Nobody in the room informs you that, ultimately, the road rules can be changed without anyone’s knowledge.

And that the most common reason a road rule might be changed is cost, not the practice of medicine.

The “secret” road rules are about managing a budget, not about managing the quality of practice. And because they are secret, anyone who thinks they have it worked out can eventually come unstuck, along with their friends to whom they’ve told their formula.

As the secret rule set changes, eventually one of your fellow drivers gets booked in a high-profile court case. You and all your colleagues take some notes and start driving a lot slower on particular roads. You change how you might normally practise.

For those that get prosecuted, only the headlines and not the details are reported in the news. Your fellow drivers might presume you are reckless and that isn’t good for your reputation. Saying you are a good and ethical driver is no defence. You can’t present a fair defence, including the one that you were not even in the driver’s seat, before the final penalty is imposed.

There is notable conspicuous silence from the driver’s associations.

This serves to undermine the legitimacy of any credible defence. Is it because some of their well-intentioned civic-minded members are tapped on the shoulder by the government to be peers in the process of prosecution? After all, the government needs some peers to help them determine that you have done the wrong thing (just three peers per case will do it, apparently).

It is only when you are booked that you find out that, for the past two years, you have been living 200 metres from a hidden speed camera. And you got booked only when you had sped enough times in one month to get noticed. However, you are going down for all the fines in those past two years, not the ones you finally got notice for.

The government then retrospectively and legally (statistically) prosecutes you for the past two years based on your driving habits in the past two weeks.

From this one month of speeding, a small sample size (fewer than 25 medical records), they may extrapolate your violations by 10 times, whether you were driving (bulk-billing or not) over two years. These significant hypothetical fines are based on a small snapshot in time.

Once you get picked up, expect your car to be tested for defects (i.e., clinical relevance, contemporary notes, what do your PSR peers think). This is where the heat is on. Saying it was an emergency and you had no time is not an excuse.

Facing such a daunting process, this will naturally slow down the way you drive and your destination.

It’s understandable that doctors may be withholding care.

Won’t see you in court

Recent court cases show how hard it has been for individual GPs to try to fight the system, and how little has changed in 25 years in terms of the power of the system over an individual doctor.

There’s little doubt now that the PSR and Medicare can’t be fought in court and that instead someone has to work on changing the law.

In some ways the government bought itself cover on this whole problem via the 2011 Federal Senate PSR Inquiry . Nothing came of it as far as GPs are concerned despite quite a bit of protest from the sector.

A High Court finding and a finding of this inquiry – that this legislation exists to protect the taxpayer – appears profoundly misguided in the context of the Healthed/TMR survey results, which suggest the law may well be systemically harming patient care.

In the absence of a provable counterargument, the High Court has deemed that a focus on how well taxpayers funds are spent must take priority over how optimally doctors treat their patients – and the High Court is hard to argue with.

A faulty O-ring in a complex system?

But there may be a small legal loophole that has still not been explored in the legal domain.

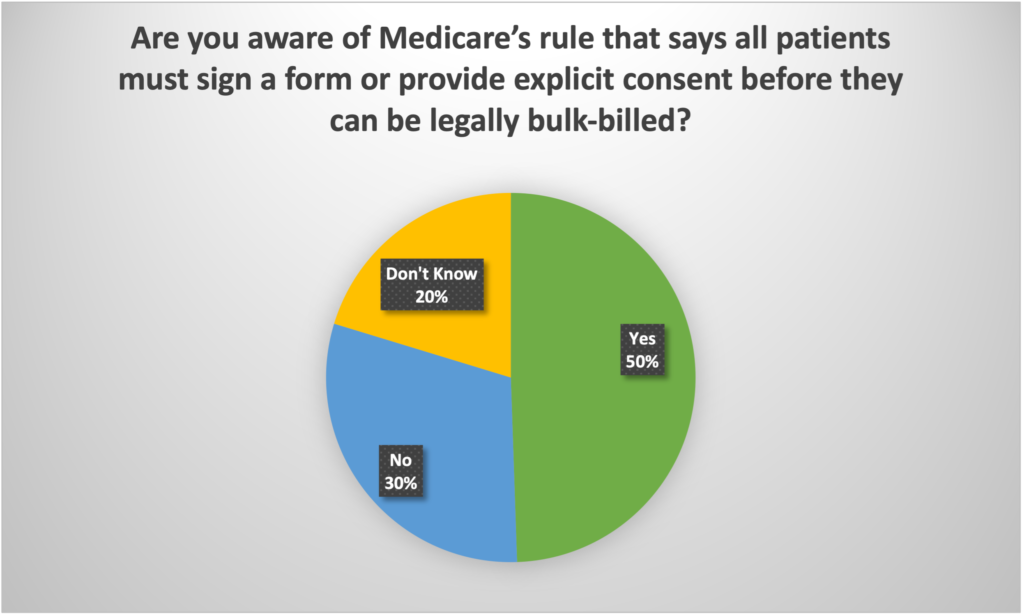

One question in the survey departs a little from the core anxiety topic to explore how much a typical GP understands about their requirement to get consent from a patient for each billing item in Medicare in order to transfer their rights to the bulk-billing rebate over to the GP.

The answer to the question is quite revealing:

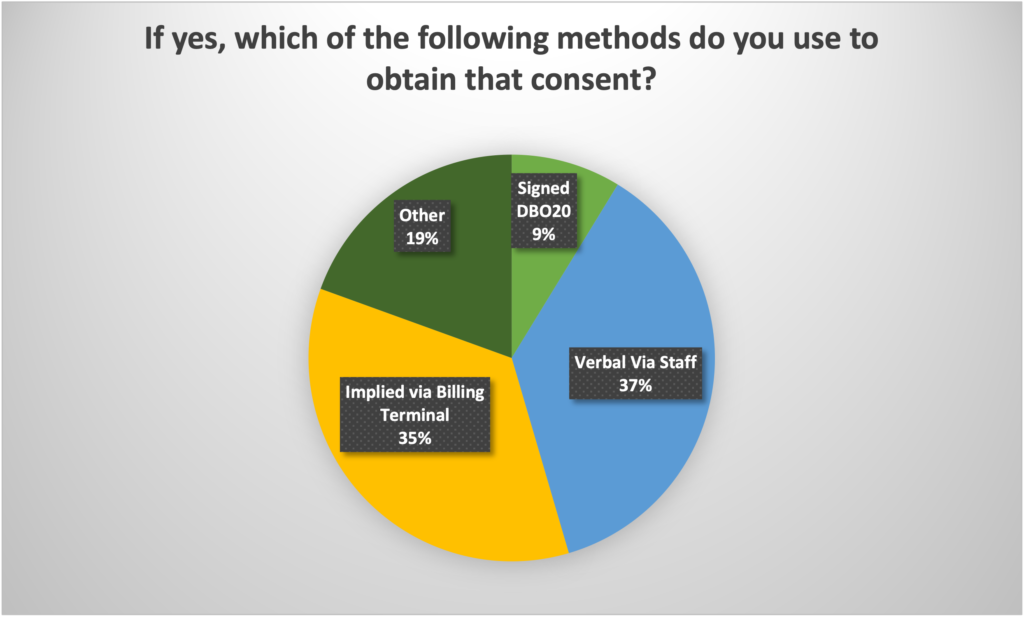

Essentially, most GPs either don’t even know the requirement exists, or they make an assumption (one that has been pushed at them by the government), that their practice receptionist pushes yes’ on the billing terminal, constitutes implied consent.

It’s a convenience for everyone. But it’s a potentially big issue for the government one day – this is the dynamite.

The government understands that it must have the consent transferred formally, from the patient for Medicare bulk-billing to the doctor, for bulk-billing to be a legal transaction. But they also understand that asking every patient to sign a DB020 form, which is the only real legal manner in which this consent could be given, is highly impractical. So, the government has suggested that a GP can obtain ‘implied consent’ for this transaction via getting a verbal OK from a patient or by the act of pressing ‘yes’ on a billing terminal.

No one wants this widely used form of consent tested legally. It wouldn’t stand up in court. And working out what to do after that could become very messy – for the government and GPs.

But the fact that 50% of GPs aren’t aware of the rule at all (and therefore we probably can assume don’t do anything regarding consent) and, of the 50% that do understand the rule, only 9% say they obtain proper consent via the signing of a DB020 form, suggests very strongly that the vast majority of all MBS claims made for bulk-billing over the years have been done, technically, without proper legal consent.

Wouldn’t it be interesting to see this technicality tested by a GP one day in the Federal Court?

The problem is that it could end up backfiring on GPs, as it could force a change that would introduce a horrific new piece of red tape that the profession doesn’t need. But the concept that the government is winning all its cases based on an assumption that all the bulk-billing transactions that a doctor has done have legally been transferred to the doctor from the patient, when they clearly haven’t, is an interesting one.

What’s in a small technicality (if it’s not really that small)?

Sometimes, in the eyes of the law, a little technicality can throw out an entire case.

Every time a question about having a patient-signed consent form is raised in the media, Medicare loses its marbles over the issue.

You need to prove you have received informed consent for bulk-billing to work.

Lawyers would have a field day arguing what constitutes consent in terms of bulk-billing. Pressing a button on a billing terminal or suggesting your receptionist obtained verbal consent very likely does not legally constitute consent. Even getting a patient to sign a D020 may not constitute consent if they don’t know what they are signing.

What would your patients say if they were in the witness box about consent being obtained from them? They would not have a clue what you are talking about.

I have yet to see a lawyer prepare a written answer to this question.

We sought the advice of Hamilton Bailey lawyers and it seems there may be a legitimate argument out there to be heard.

Hamilton Bailey said it would be interesting to note a judge’s views on the following questions:

- Is there a requirement to pre-confirm that the doctor was bulk-billing each patient with appropriate consent?

- If consent is deemed not to be appropriate, does this invalidate or curtail the PSR laws?

- Would evidence that bulk-billing consent has been given (rather than it be assumed) first need to be established before any Medicare investigations or subsequent prosecutions and/or liability could proceed?

- Would a private-billing (non-bulk-billing) doctor have more or fewer rights if they did not bulk-bill?

- Could it be as simple as: if you stopped bulk-billing, most of your Medicare audit issues would be solved, as you would be outside the legal jurisdiction of Medicare for most things?

- What about if it were found that in nearly all conditions, patient consent has never been formally assigned? Would that have the same effect?

Time might tell whether these questions might constitute a sort of “O-ring” problem for Medicare. Or an opportunity for some downtrodden defence lawyer of a GP.

For those that are into technical arguments, the starting point is to look at the S.20A Health Insurance Act 1973, which outlines proof of consent.

Doctors must receive a signed bulk-billed patient consent form. Essentially what this means is that the doctor has agreed with the patient to assign the responsibility for the payment of their bill to the government.

The doctor agrees the government is legally allowed to pay you what they feel like.

Technically, you have agreed that it is a “Good Samaritan” gesture (you have agreed to provide your services for free) and no longer have a legally enforceable contractual agreement or debt with the patient or the government.

In other words, where a doctor agrees to bulk-bill, they have legally waived their rights to collect any income from anyone – the patient and/or the government. There is no legal obligation to pay. It is now at the Commonwealth’s discretion. You have just given up your fundamental Constitutional right to claim property.

Remember the movie The Castle?: “ acquisitions by the Commonwealth other than ‘on just terms. S. 51(xxxi) of the Constitution is not allowed.’”

If the Commonwealth did not observe this rule, it may be considered theft.

I am not sure whether, if doctors were across this technical point, they would agree to bulk-bill in the first place. Most informed people would at the very least be very wary of what was going on.

This principle was established in the 1994 High Court Health Insurance Commission v Peverill case.

The importance of this case could legally mean that if the PSR has found you guilty of inappropriate practice (for example, on only 25 medical records) the Department could claw back two years of your income without securing evidence that you did secure appropriate consent.

But is it sufficient to presume that informed bulk-billing consent has been provided to each patient they seek to make money from?

Many lawyers would argue this should involve more than a simple tap and/or signature at the front desk.

Legally this means that if the patient needs to be informed for it to be valid, then doctors have agreed to bulk-bill.

Where to from here?

You could consider reducing or stopping bulk-billing, as one option. It’s not as crazy as it may seem. It will depend on where you are now, how attached your patients are to your service and how you communicated the change.

Most patients, after paying your medical fee via EFTPOS or their credit card, won’t remain out of pocket for long. Ironically, the technology now exist for them to be out of pocket literally for seconds, but the government won’t introduce these systems because it would probably induce a lot of GPs to try kicking the bulk-billing habit.

An understanding patient cohort and straight-through billing via new web-based payment protocols would also allow you to charge over and above the Medicare rebate in much smaller increments over time, which could change your whole financial paradigm.

To achieve the above, on the day of the consult, you could charge medical benefits only but make sure the patient does not assign the debt to the government. This means the debt remains the ultimate responsibility of the patient and not the government.

Medicare will usually pay the patient back into their nominated bank account or other practical means, within 24 hours, for any Medicare rebate owing. It could do it instantly these days using cloud-based billing systems, but it won’t because this would make it much easier for all GPs to do the above.

A more sensible way forward

There is a more certain win-win solution out there if GPs want it: establish an independent not-for-profit, peer-reviewed international healthcare standards and ethics board.

A similar one exists in the accounting profession and the concept has been adapted. The next thing doctors and healthcare workers should be pushing from the ground up is their professional memberships to provide real protection for their patients and providers – and a fair go.

The International Healthcare Standards and Ethics Board project is something that has been endorsed by leading international expert Professor Bill Runciman and has the support of Professor Ian Olver. It’s worth a look.

This article had its origins in an article first published at healthandlife.com.au HERE

David Dahm is a registered tax agent, CEO and founder of the national medical and healthcare chartered accounting firm Health and Life, and global founder and CEO of not-for-profit project the International Healthcare Standards and Ethics Board – https://www.ihseb.org/

Disclaimer: Please seek appropriate legal and accounting advice. This information is for general information and discussion only