It depends on who you are, and who you ask.

GPs will be able to handle the increased demand for reproductive carrier screening but extra resources and support services are needed, experts believe.

November 2023 saw the introduction of a new MBS item number – 73451 – which funds genetic screening to determine whether an individual (and their partner) who are pregnant (or planning pregnancy) are carriers of pathogenic or likely pathogenic variants of genes causing cystic fibrosis, spinal muscular atrophy and fragile X syndrome.

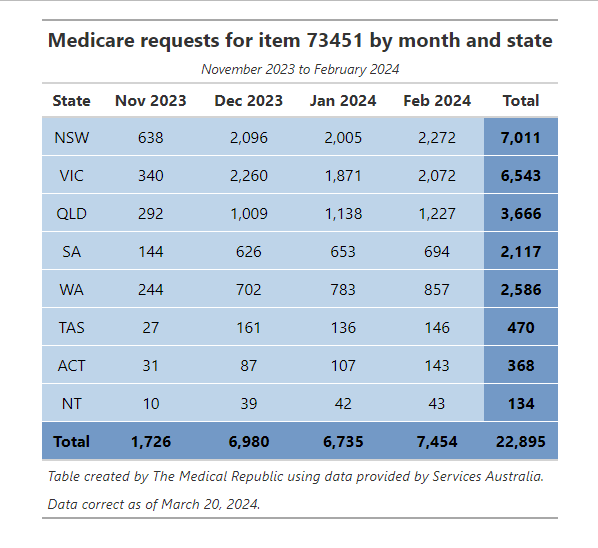

There have been over 22,000 requests for the three-gene screen between November 2023 and February 2024, according to data from Services Australia. All jurisdictions have seen an increase in the number of requests during this period, with NSW and Victoria accounting for over half of all requests.

Dr Tristan Hardy, an obstetrician and gynaecologist and medical director of genetics at Monash IVF Group, described the most recent data as a “slow and steady uptake” while acknowledging “there’s still a long way to go”.

“There are over 300,000 deliveries per year in Australia, and then there are also people planning pregnancy. There could be up to half a million people who are considering taking the test in any given year,” he told The Medical Republic.

The response to the introduction of the new MBS item has experts in the area questioning whether Australia is ready for the expected increases in requests for reproductive carrier screening.

A recent perspective piece, published in the Medical Journal of Australia, suggests we are not.

“Australian clinical genetics services (including both clinical geneticists and genetic counsellors) are in high demand, having long waitlists and are under-resourced to manage the surge of increased chance couples who will inevitably be unveiled by the new MBS item,” the authors wrote.

“The workforce implication of the implementation of three-gene reproductive carrier screening are considerable. Management of the one in 240 increased chance couples will likely be undertaken by already stretched hospital-based clinical genetics services, with flow-on effects to other specialties.

“Ongoing education of primary care health practitioners is essential at minimum to manage these demands, as most pre- and post-test genetic counselling will be delivered by general practitioners.

“[This] highlights the need for government bodies and policy makers to prioritise the upskilling and education of non-genetics professionals, while allocating resources to the already over-stretched clinical and laboratory genetics services.”

Dr Ka-Kiu Cheung, chair of the RACGP specific interests in antenatal and postnatal care group, said GPs would be able to handle conversations with families interested in genetic screening.

“GPs are very good at incorporating a lot of new information that pops up across a person’s lifespan,” Dr Cheung told TMR.

“For example, 20 years ago there were only three classes of medications for diabetes, and now there’s a such broad range of treatments we have at our disposal that we need to know about to discuss with patients.

“Over time, GPs will incorporate this into their prenatal and antenatal consults and develop processes on how to introduce this topic in a simple, culturally appropriate way to families seeking care and then following that up with more information [as needed].”

Dr Hardy agreed with calls for additional resources – financial or otherwise – to support the increased uptake and delivery of reproductive carrier screening following the introduction of the MBS item in November last year.

“The amount of money received by the laboratory for doing the three gene test [$400 per test] is barely enough to continue operating. It’s not as though there’s room within [the amount] that a laboratory could easily fund a genetic counsellor, which is otherwise not paid for by the MBS and is not easily accessible by the public.

“There’s a big workforce education issue as to how do you integrate [ongoing genetic education] into very bust clinical care in general practice and in obstetrics and gynaecology. Integrating genetic counselling into practice, and upscaling this over a short period of time, is not going to be easy.

“Genetics has changed so much and so rapidly that even if you taught it in medical schools – which it typically isn’t – it would be outdated by the time you were practising as an independent clinician. It’s hard to get all this education in.”

Despite these challenges, Dr Hardy said it was possible to provide the training required to ensure a healthcare professional can give general, yet quality, counselling, outlining some key points for GPs.

“You have to understand the basis of the conditions and the tests we perform for those conditions. Even though it’s only three genes, there can be health implications if you’re found to be a carrier,” Dr Hardy told TMR.

One such example are the female carriers of fragile X syndrome. Women who are carriers have an increased likelihood of developing fragile X tremor ataxia syndrome, of developing fragile X-associated premature ovarian insufficiency, in addition to having an increased chance of having a child with fragile X.

“Adequate counselling needs to address all possibilities,” the MJA perspective authors wrote.

Dr Cheung recommended interested GPs explore available guidelines from the RACGP and RANZCOG around genomics and genetic carrier screening.

Dr Hardy and Dr Cheung both highlighted the importance of knowing what services and options were available to couples whose results indicated they were a high chance of having an affected child.

“I always direct people to HealthPathways,” Dr Cheung explained. “If your local HealthPathway doesn’t have genetic carrier screening, I would suggest advocating the GP liaison unit at your local PHN or hospital and asking them so that information is ready and at hand when you need it.”

“[The next steps are] very context dependent, both for the individual patient and in terms of where you are geographically practicing medicine, whether you’re public or private, and so on. [But] the purpose of carrier screening is informed decision making. It is not the avoidance of the birth of a child with a genetic condition,” said Dr Hardy, pointing towards the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics guidelines in this space.

The options available to individuals and couples depend on whether testing is done before or after falling pregnant.

“Early testing enables individuals to explore various options, such as in vitro fertilisation with pre-implantation genetic testing, to reduce the risk of passing these conditions to their children,” Dr Hardy told TMR in March.

Related

Other options to reduce the risk of an affected pregnancy include adoption, fostering, or using a donor egg, sperm or embryo in combination with assisted reproduction technologies. Choosing not to have children is another potential option.

Delaying screening until after falling pregnant limits the options available to couples who are identified as carriers.

“In this setting, families can progress and gather information about a condition and may choose to test their pregnancy for the condition,” the authors of the MJA perspective wrote.

“If the fetus is shown to be affected by the condition, this allows discussion about targeted perinatal care, with anticipation of medical needs and outcomes after birth, or the potential termination of pregnancy.”

Dr Cheung said GPs would play a key role in discussions around carrier screening due to their experience in having potentially difficult conversations with patients.

“We can be quite sensitive to knowing the needs of the couple and seeing what kind of conversation needs to be had,” he said.

“But hopefully we have broached the possibility of a high-risk result and had a preliminary conversation about options as part of our pre-test counselling.”