Characterising the type of asthma an infant has will help to individualise treatment and assess the risk of severity or persistence

Asthma comes from the Greek word “aazein”, meaning to exhale sharply through an open mouth, which was coined by Homer after appearing in The Iliad.

It was further described by Plato and Hippocrates and has continued to be a feature in medical literature since.

The prevalence of asthma is increasing in developing countries, while it appears to have plateaued in older children in some developed nations.1,2

Australia continues to have one of the highest prevalence of disease, at 20% of the population affected.3

Despite our long-term relationship with asthma, its diagnosis continues to be problematic, particularly in the younger age groups.

The question of whether infant asthma is a real entity has been asked previously and is the focus of this review.

DEFINITION AND DIFFICULTIES IN DIAGNOISING INFANTS

A recent consensus statement was commissioned by The Lancet4 calling for a reworking of the definition of asthma.

The initial description of asthma by Hippocrates was not of a disease but rather of a symptom. Since then, there have been multiple attempts to define asthma in terms of its clinical features and pulmonary function characteristics, however, there remains a lack of consensus on how to diagnose it.

The National Asthma Council Australia5 defines asthma as the presence of characteristic respiratory symptoms, including recurrent wheeze, cough and dyspnoea, in the presence of reversible small airways obstruction in response to a bronchodilator.

There is a noticeable absence of age criteria in the council’s clinical definition.

The difficulties in diagnosing asthma in pre-schoolers, especially those aged under three years, is well known and several studies have tried to determine methods to identify those too young to undergo objective pulmonary function tests but who are given an asthma diagnosis when testing is possible.

This difficulty stems from the fact that many infants and toddlers wheeze, but do not go on to qualify for an asthma diagnosis. This is due to the increased compliance of large airways, the elasticity of their chest walls, and the small diameter of the peripheral airways which increases their resistance.6

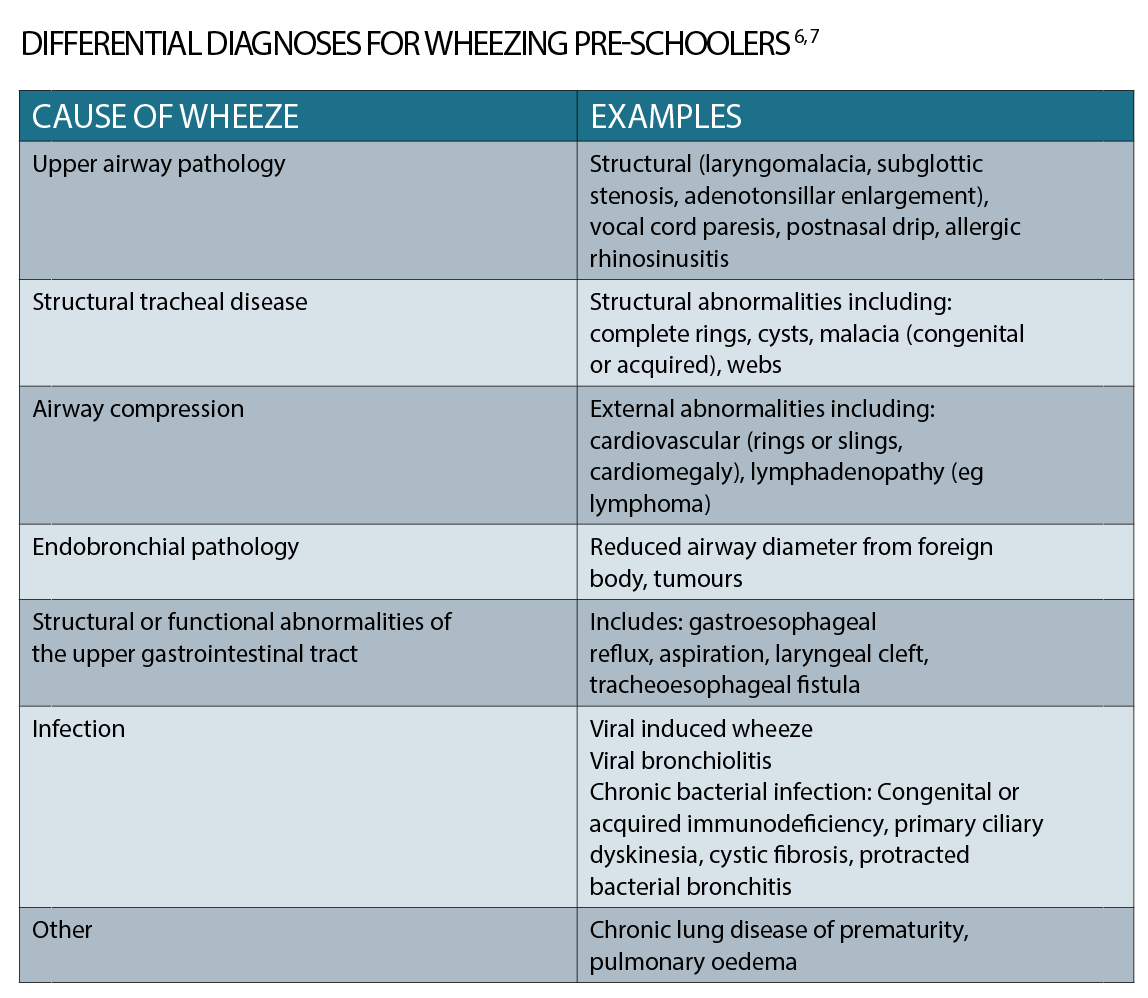

Additionally, there are a myriad of differential diagnoses for the wheezing pre-schooler which need to be considered (See table).

RISK FACTORS

Attempts have been made to identify factors that increase the likelihood that a wheezing pre-schooler will obtain an asthma diagnosis in the future.

A Melbourne based study8 examined early-life risk factors for the development of one of five wheeze phenotypes in children who had at least one immediate family member with an atopic disease.

Of these five, three phenotypes were associated with an increased prevalence of wheeze at 12 years of age.

Risk factors identified in children who wheezed by six months and up to three years were both parental, such as a family history of asthma, parental smoking, or personal, such as a doctor diagnosis of eczema at or before six months of age, a lower respiratory tract infection, attendance at childcare by 12 months, sensitisation to a food by 12 months or to an aeroallergen by two years, and obesity at two years.

These findings are in keeping with other international studies.

The Tucson’s Children Respiratory Study followed 1246 children born between May 1980 and October 1984 and has added valuable epidemiological insights into the outcomes of preschool wheeze.9

The study developed four categories based on the wheezing history of the children, namely:

1: never wheezed

2: transient early wheezers (at least one episode of wheeze with a lower respiratory tract infection in the first three years with resolution by six years)

3: late-onset wheezers (never wheezed in the first three years of life but wheezed at six years)

4: persistent wheezers (at least one episode of wheeze with a lower respiratory tract infection in the first three years with continuation of wheeze at six years).

These categories have been used to examine characteristics of wheezing pre-schoolers that predict a future asthma diagnosis.

Factors increasing the risk include:

• a personal history of eczema9,10,11

• sensitisation to foods and/or aeroallergens9,10

• a doctor diagnosis of allergic rhinitis9,10

• parental asthma9,11

• male gender9,11

• bottle feeding8,11

• obesity8

Persistent wheezers have altered immunity with a significantly higher level of immunoglobulin E (IgE) at nine months of age compared with those children who have never wheezed.9

Recurrent diagnoses of bronchiolitis, particularly when wheeze is a prominent feature, has long been thought of as an early harbinger of an asthma diagnosis.

A history of respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) infection or pneumonia increases the risk of recurrent preschool wheeze and a future diagnosis of asthma.12

EARLY LUNG CHANGES

Several studies have examined the correlation between preschool wheeze and lung function tests. The Tucson Children’s Respiratory Study9 found a significant reduction in the maximal flow in functional residual capacity in early transient and persistent wheezers compared with children who never wheezed, with this change persisting at six, 11 and 16 years of age.13 This suggests that abnormal lung function is established early in life.

A review of infant lung function in respect to a history of wheeze14 suggests that lower lung function predisposes to wheeze-associated lower respiratory tract infections later in life.

The above findings support the idea that vulnerable infants are set up to wheeze early in life. It highlights the heterogeneity of asthma in terms of its timeline and cause.

Several factors – including personal and family history of atopy, male gender, no or reduced duration of breastfeeding – facilitate identification of wheezing pre-schoolers at increased risk of persistent asthma.

TREATMENT OF PRESCHOOL WHEEZE

Once the recognition of preschool wheeze has been made, management needs to be formulated to fit the most likely diagnosis.

The Australian Asthma Foundation5 suggests a trial of an inhaled bronchodilator in children six months of age or older who present with wheeze and increased work of breathing, to assess if there is a reversible component. Inhaled bronchodilators have been shown to be effective in the preschool age, although this may be reduced in those under two years.5

Timely review should occur soon after giving the bronchodilator, to determine whether it was effective in reducing airway obstruction by assessing air entry, the presence of adventitious sounds on auscultation, and decrease in work of breathing.

When a child aged one to two years presents with persistent wheeze or wheeze that has multiple triggers sodium cromoglicate can be considered as a preventer with regular reviews for symptom control. Similarly, for a child aged two to five years of age with frequent intermittent asthma, the consideration of a montelukast inhibitor may be undertaken.

Inhaled corticosteroids have not been found to offer significant advantage in pre-schoolers with regards to reducing severity nor preventing hospitalisation.

An attempt to identify reversible or avoidable contributors of asthma is also important. This includes treatment of eczema and allergic rhinitis, as well as managing obesity and encouragement of breastfeeding duration.

CONCLUSIONS

Asthma started its history in medicine as a symptom description but has since become a catch-all for reversible recurrent/persistent wheeze and dyspnoea.

Asthma covers a heterogeneous group of respiratory diseases in terms of underlying pathology, contributors and duration.

The concept of infant asthma remains problematic and unresolved, reflecting the lack of standardised diagnostic criteria for asthma.

It appears that the lung inflammatory processes and adverse functional changes occur in early life. This means a window of opportunity exists to prevent progression to symptoms.

It is possible for an infant to meet a diagnosis of asthma if they wheeze, cough, have dyspnoea and respond to an inhaled bronchodilator.

However, it is more important to define the type of asthma they may have.

Characterising the type will help to individualise treatment and assess the risk of severe or persistent asthma, providing meaningful information for the child and the family.

Dr Michelle Barnes is a general paediatrician with a special interest in allergy. When she is not working in the Department of Allergy and Immunology at The Children’s Hospital at Westmead, Sydney, she has private rooms in Castle Hill.

References:

1. Asher MI, Montefort S, Bjorksten B, Lai CKW, Strachan DP, Weiland SK, et al. Worldwide time trends in the prevalence of symptoms of asthma, allergic rhinoconjunctivitis, and eczema in childhood: ISAAC phase one and three multicountry cross-sectional surveys. Lancet (2006); 368: 733-743.

2. GBD 2015 Chronic Respiratory Disease Collaborators. Global, regional, and national deaths, prevalence, disability-adjusted life years, and years lived with disability for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and asthma, 1990-2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. Lancet Respir Med (2017); 5: 691-706.

3. To T, Stanojevic S, Moores G, Gershon AS, Bateman ED, Cruz AA et al. Global asthma prevalence in adults: findings from the cross-sectional world health survey. BMC Public Health 2012, 12:204.

4. Pavord ID, Beasley R, Agusti A, Anderson GP, Bel E, Brusselle G, et al. After asthma – redefining airways diseases. A Lancet commission. Lancet (2017); 391(10118):350-400.

5. National Asthma Council Australia. Australian Asthma Handbook, Version 1.3. National Asthma Council Australia, Melbourne, 2017. Website. Available from: http://www.asthmahandbook.org.au

6. De Benedictis FM and Bush A. Infantile wheeze: rethinking dogma. Arch Dis Child (2017); 102: 371-375.

7. Khetan R, Hurley M, Neduvamkunnil A, Bhatt JM. Fifteen-minute consultation: an evidence-based approached to the child with preschool wheeze. Arch Dis Child Educ Pract Ed (2017); 0: 1-8.

8. Lodge CJ, Zaloumis S, Lowe AJ, Gurrin LC, Matheson MC, Axelrad C, et al. Early-life risk factors for childhood wheeze phenotypes in a high-risk birth cohort. J Pediatr (2014); 164: 289-294.

9. Martinez FD, Wright AL, Taussig LM, Holberg CJ, Halonen M, Morgan WJ et al. Asthma and wheeze in the first six years of life. NEJM (1995); 332 (3):133-138.

10. Guilbert TW, Morgan WJ, Zeiger RS, Bacharier LB, Boehmer SJ, Krawiec M, et al. Atopic characteristics of children with recurrent wheezing at high risk for the development of childhood asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol (2004); 114 (6): 1282- 1287.

11. Sherriff A, Peters TJ, Henderson J, Strachan D and the ALSPAC Study Team. Risk factor associations with wheezing patterns in children followed longitudinally from birth to 31/2 years. Int J Epidemiol (2001); 30: 1473-1484.

12. Schwarze J and Gelfand EW. The role of viruses in development or exacerbation of atopic asthma. Clin Chest Med (2000); 21(2): 279-287.

13. Morgan WJ, Stern DA, Sherill DL, Guerra S, Holberg CJ, Guilbert TW, et al. Outcome of asthma and wheezing in the first 6 years of life: follow-up through adolescence. Am J Respir Crit Care Med (2005); 172: 1253-1258.

14. Sanchez-Solis M and Garcia-Marcos L. Lung function in wheezing infants. Front Biosci (2014); 6: 185-197.