Medicine really has come a long way in the century since the Spanish flu.

We’re researching covid-19 in a fast-paced world with new data becoming available all the time.

We track which interventions work well and which ones don’t.

But in 1918, during the Spanish flu pandemic, the world was a different place. No one was entirely sure what caused influenza. By the time health authorities began to find out, it was too late.

Our knowledge about viruses was limited in 1918, but we knew about bacteria. People who died of flu had bacterial infection in their lungs. However, this threw researchers off track because these were secondary infections, not caused directly by the flu.

With this lack of knowledge, it was still an anything-goes medical research world. There were unregulated vaccine trials and lots of hype for the latest “cure”, even in respectable medical journals.

More than 100 years on, controversial “cures” for covid-19, such as ivermectin, are making the headlines, being reported in medical journals and are being promoted by doctors and politicians.

Here’s what we know about the Spanish flu “cures” of the day, whisky included.

Read more: I asked historians what find made them go ‘wait, wut?’ Here’s a taste of the hundreds of replies

Doctors, pharmacists and nurses had cures

Doctors developed and used some of these cures for the flu. Sydney’s chief quarantine officer, Dr Reid, treated patients in March 1919 with 15-grain (1 gram) doses of calcium lactate every four hours, and a “vaccine” containing influenza and pneumococcus bacteria. In 203 cases, he had no deaths.

Calcium lactate is used today to treat low levels of calcium in the blood. But Dr Reid’s doses are well above the current recommended daily level.

Chemists were also busy making and selling their own influenza cures. J. Reginald Albert McAlister of Guyra in regional New South Wales advertised his 1919 patented mixture as curing influenza at once.

People even listened to nurses — who at the time were usually the least important people in the health-care system — about cures for the Spanish flu.

Nan Taylor, a New Zealand nurse, advocated whisky — lots of it, including gargling and drops up the nose. She also recommended quinine and castor oil.

Nurse Kate Guazzini cared for Spanish flu patients in South Africa in late 1918, and caught the flu there before moving to Sydney. She said:

I was kept alive on brandy and milk for six weeks […] That, with quinine and hot lemon drinks, were found to be the only effective remedies.

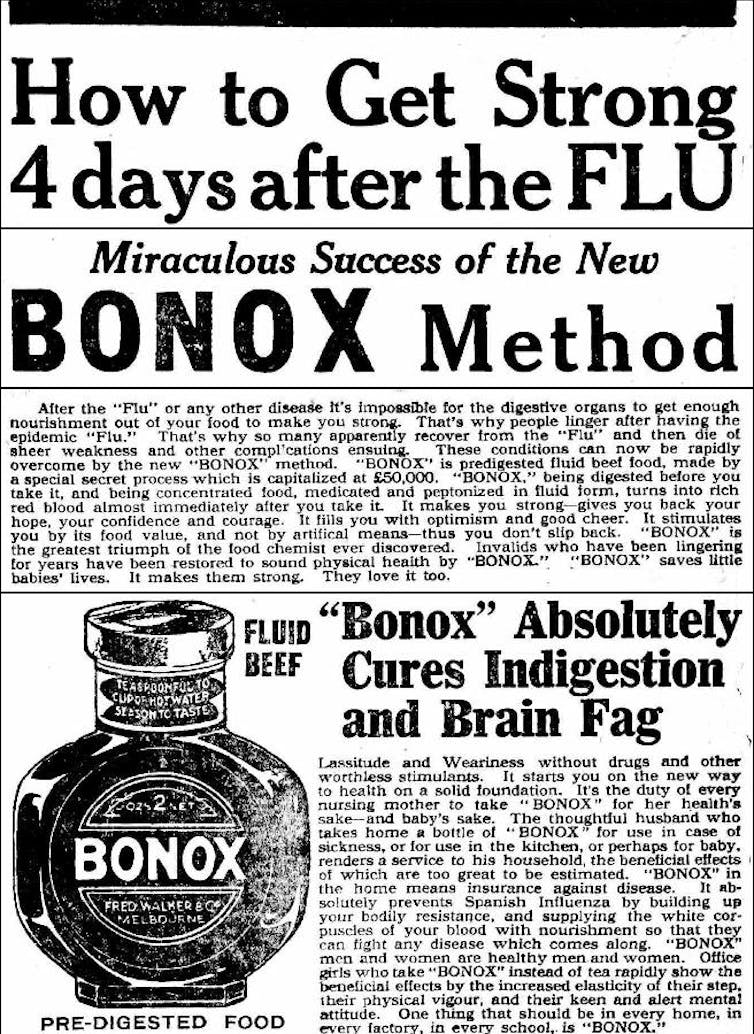

Food manufacturers linked themselves to flu cures. In 1919 a brand new beef extract, Bonox, had just hit the Australian market, and the flu epidemic was a great marketing opportunity. Bonox was advertised as a sure way to recover your health and strength after the flu.

News of ‘cures’ spread far and wide

In much of Australia just after WWI there were often no doctors close by. So many people were used to dosing themselves with homemade potions and remedies. They shared their prescriptions in the pages of local newspapers.

Between 1918 and 1920, Australian newspapers were flooded with Spanish flu cures of all kinds.

In October 1918, a journalist at Victoria’s Bendigo Independent lamented:

Cures? My goodness me, the vast amount of cures on the market are positively frightening, and everyone has a favorite cure. I pin my faith to one, you to another. There’s a certain influenza mixture that, taken in the early stages, is regarded as a certain cure by one large section […] Asperin [sic] is the cry of another batch of victims, and they tell you that that drug does the trick. ‘Try whiskey and milk taken hot and taken often,’ is the advice of others who have had it. But one and all end in the same way: ‘Go to bed and stay there till the thing leaves you.’

Aspirin was very popular as a Spanish flu treatment worldwide. But people sometimes took it at dangerously high doses, which may have boosted the number of deaths attributed to the flu.

In the absence of many other treatments, government authorities promoted aspirin, along with quinine and phenacetin.

The pain killer phenacetin is now banned because it’s linked to kidney and urinary tract cancers.

Like aspirin, its overuse might have boosted the Spanish flu death rate.

Read more: 100 years later, why don’t we commemorate the victims and heroes of ‘Spanish flu’?

They’re using it in America

Like today, Australians were also eagerly reading about overseas experiments, and wanting to try these cures locally.

In June 1919, the Richmond River Herald reported:

On Friday we published the following New York cable: — ‘Dr. Charles Duncan, at the Convention of the American Medical Association, said the cure for influenza was one drachm of infected mucus pasteurised and with filtered water injected subcutaneously … Yesterday (says Tuesday’s Tweed ‘Daily’) a youth was seen inquiring for a chemist, having in his hand the above clipping and sixpence, his object being to secure that amount’s worth of the ‘cure.’ Several others, it is understood, have also been inquiring into the same matter, with a view to ‘having it made up’ locally.

Some of these cures lingered

Once the Spanish flu pandemic was over, many of the cures remained. Most of them, like aspirin, incorporated the threat of influenza into regular advertising.

Some, like quinine, have made a reappearance during the covid-19 pandemic.

And one of the most commonly recommended cures — whisky taken at frequent intervals — hasn’t lost its popularity.

Philippa Martyr, lecturer, pharmacology, women’s health, School of Biomedical Sciences, The University of Western Australia

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.