Why are we spending more than $1.2 billion a year on PHNs when some clearly don’t have effective governance, transparency, audit and review mechanisms in place?

If you’ve not followed the unravelling of Northern Queensland Primary Health Network over the past few months, then you can get up to speed quickly before you read this story by reading the full open letter of one of the two GP board members who resigned recently (it’s also at the end of this article).

Dr Nicole Higgins resigned from the NQPHN board, citing what she perceived as serious possible conflicts of interest among the board and the PHN membership, in part, in dealing with the secretive Queensland pharmacy prescribing trial through the region.

Dr Higgins suggested that the 11 members (local health organisations that act more or less as shareholders of PHNs) of the PHN were acting like “shadow directors” and running the PHN behind the scenes by controlling the board members.

Section 15 of the NQPHN constitution states that:

Management of the Company: (a) Subject to this Constitution and the Corporations Act, the activities of the Company are to be managed by, or under the direction of, the Board.

Where does that management stop and member control start, is what Higgins was starting to question in her letter.

Members, as effective shareholders, obviously will have some say in the running of the organisation. But if they are really controlling a lot of the direction and running of the group, then the NQPHN does have a very serious governance problem, even according to its own constitution.

NQPHN resigned its involvement in the controversial pharmacy prescribing trial by taking itself off the expert steering committee in February, but not before some worrying revelations about key directors not declaring any potential conflict beforehand.

Although the constitution of the PHN clearly outlines terms for directors declaring any potential conflict, the chair of the NQPHN board and the organisation’s representative on an expert steering group set up by Queensland Health to advise on the pharmacy prescribing trial, did not declare to the committee he owned a large local pharmacy chain (Alive Pharmacy Warehouse Group) in the area.

Not initially anyway.

Nor did the Pharmacy Guild see that as a problem, even though the co-owner of the pharmacy chain was the national president of the Pharmacy Guild of Australia, Trent Twomey.

Twomey was also the previous chairman of the QPHN and the Pharmacy Guild is one of the 11 members that effectively make up the shareholders of NQPHN.

There is nothing illegal about any of this. But none of it is a good look for NQPHN, nor PHNs in general. You can’t see any fire yet, but there’s a fair bit of smoke up there in Northern Queensland.

As a result of the furore, Nick Loukas stepped down as chair of the PHN, and quit the pharmacy trial expert committee.

However, he is still a director of the PHN.

The NQPHN constitution states:

Any Director who has a material personal interest in a contract or proposed contract of the Company, holds any office or owns any property such that the Director might have duties or interests which conflict or may conflict either directly or indirectly with the Director’s duties or interests as a Director, must give the Board notice of the interest at a Board meeting.

Loukas may of course have one excuse.

Until early this year, the real and controversial plans for the trial were a tightly held secret within Queensland Health.

But the trial has been the brainchild of the Pharmacy Guild. Would the national president of the guild, who is the business partner of Loukas in a large pharmacy operation in the North of the state, have known the secret details of this trial beforehand?

If you’re wondering if the Queensland pharmacy trial might be pointing to some slightly wayward governance as far as the NQPHN is concerned, then so too apparently is the Department of Health, which has launched an independent review of the organisation.

Last month, when a group of more than 70 GPs wrote to the DoH complaining about serious issues with NQPHN, the department told The Medical Republic that “the Commonwealth takes any concerns raised about PHNs very seriously”.

“Given the nature of the concerns raised about NQPHN governance and tensions with the general practice community, the department is preparing to conduct an independent review,”. it said

It added that the North Queensland Pharmacy Scope of Practice pilot was “not consistent with Commonwealth medicines policy“.

Such an intervention might be more about the annoyance the federal government feels about the Queensland government in proposing a trial (and with it, possible state-based legislation) that contravenes Commonwealth medicines policy than about PHN governance.

But maybe not. Last year, the DoH apparently ran three separate reviews of PHNs on the grounds of checking governance, which have never been made available, and commissioned a PWC review, which it says it has not yet received.

The Medical Republic asked for some terms of reference for the NQPHN review to try to understand better what the DoH is worried about outside of the Queensland pharmacy trial. The Department responded:

The review of the NQPHN is being conducted under the PHN program assurance framework. It will consider issues raised in the letter [from GPs], as well as broader governance matters.

The audit will be conducted over coming months and is expected to report in 2022. The reports from audits of this kind are generally treated as confidential. Any public release would be a matter for government.

All PHNs continue to be considered against the Performance and Quality Framework as a part of their 12 month reporting obligations.

Which means we can probably look forward to not hearing about this ever again.

If you look at NQPHN’s constitution and financial reports to see if there are any other possible issues that might point to the sort of systemic issues that Dr Higgins is hinting at you quickly see some possible problem areas.

The first issue we encountered was that while the constitution refers to a Members Charter, which outlines the roles and responsibilities of members, we could not find that charter anywhere (we think it should be included in the reporting on the ACNP website) and when we asked NQPHN to send us one, we didn’t get any reply.

NQPHN is a not-for-profit company, so it must report key financials and governance performance to the Australian Charity and Not for Profit commission. Its financial reporting is sparse, to say the least; just a few pages of the very basics. There is no sign of the Members Charter in there, or on their website, which is unusual because in most companies, a shareholder agreement goes hand in hand with a constitution. You can’t really work out how a company is working without having both on hand.

Given members are effectively the shareholders of NQPHN and the constitution points to a Members Charter, the charter, which outlines responsibilities of members and the framework within which members operate, is the equivalent of a shareholders agreement.

We aren’t saying the Members Charter doesn’t exist. But given the important nature of that document, it should be easily, freely and publicly accessible, and it doesn’t appear to be.

Member control and possible financial conflict

The constitution of NQPHN clearly states that members should not profit from the venture:

4.3 No profit to Members

No part of the income or property of the Company will be transferred directly or indirectly to or amongst the Members.

Of course, if you have shareholders (members) that comprise large healthcare provider organisations within your region as a PHN, especially hospital-based members, you are very likely to run into the problem that some of them may end up as the best organisations to award contracts too, or indeed, the only ones who can do a contract.

In the case of NQPHN, almost $6.5 million worth of transactions were conducted last year with seven of the 11 members of the organisation.

While this might appear to be in conflict with section 4.3 of the constitution, in accounting land, you are often able to get around any such conflict if you couldn’t reasonably get the service anywhere else (which is entirely feasible as far as Hospital and Health Services are concerned), and the contract is either on an arm’s length basis (for example, no one in the NQPHN board or members had anything to do with the contract) or that the “terms and conditions of the transactions were no more favourable than those available, or which might reasonably be expected to be available, in similar transactions with non-key management personnel related entities on an arm’s length basis”.

The last quote is directly from the NQPHN financial report.

So, nothing to see here?

The problem for the NQPHN, and possibly many other PHNs across the country as a result of this scandal is, if we do have the organisation being “shadow run” somehow, and we have the chair of the organisation ending up so conflicted after the fact he needs to resign as chair, how are we to trust what is boiler-plate wording in a very sparse annual financial report, including a similarly boiler-plated one-page letter from the group’s auditor?

There is no evidence of an audit to check that the wording of the report – arm’s length and on normal commercial terms – is in fact what happened.

Section 4.3 of the NQPNH constitution was not put there for nothing. It is a typical company safeguard.

It is there to make certain that members aren’t influencing commercial contracts in any way, shape or form, and neither are board members, if they are connected to members.

The 2021 financial report says plainly that this didn’t happen – that the $6.5 million of contracts were either arm’s length or competitive on normal terms.

But the wording in the financial report is just a boiler-plate sentence, with nothing to back it up, other than a one-page letter from an auditor, saying they think the financial report is viable.

If the members are running the show at the NQPHN, the words in the 2021 annual report will need to be tested properly by someone. Given that it looks like the PHN has experienced conflict high at the board level, someone is now going to have to prove that there is none at the member level.

Perhaps this is what the DoH is going to set about doing now with its review.

Accounting terminology and standard practices notwithstanding, regularly sending 10% of your funding income from the federal government to members of your company, who now are suspected of “shadow” controlling your organisation, is a worry.

For one thing, if the members are controlling the PHN, and not the board, Section 4.3 becomes a lot more meaningful for audit of this organisation.

Member control of membership

Dr Higgins expressed a worry that an application by the RACGP to become a member of the NQPHN kept being buried and or delayed by the board and the members. She said that multiple inquiries as to what had happened to the application were met with stonewalling by various parties in the organisation.

Dr Higgins’ concern has been reiterated recently by the Queensland chair of the RACGP, Dr Bruce Willett. Apparently the RACGP has been trying to become a member of the NQPHN for more than 18 months now.

Section 7.4 (f) of the NQPHN constitution states:

As soon as reasonably practicable after an application for Membership has been received, the Members will meet to vote to accept, subject to conditions, or reject the application, after having first consulted with the Board in accordance with clause.

There are a few issues of governance here that are now definitely apparent.

Why is it that the members get to decide who is good to join as another member? Shouldn’t that be a matter for the board and the management of the company, who are charged with the effective running of the company?

If this is really a community organisation, how does the community have a say here, if the organisation is controlled by what could be seen as a cabal of founding interested parties that hasn’t turned out to be fully representative of the local primary care community.

The way this constitution is set up, the founding members are in control of who joins and leaves as members. Not even the DoH can intervene.

If the members are in the end running the PHN in a manner that is more in the interests of the members than the community, who stops that?

If the membership of your PHN somehow drifts one way or another, or has been established one way or another for historical reasons – for example, you are dominated by hospital people and not primary care people, as the NQPHN is – then you can block and control who gets to be represented at the PHN.

This, by the way, is not just an issue in the constitution of the NQPHN.

How is the RACGP not an acceptable PHN member?

Why would NQPHN be stalling on accepting the RACGP as a member?

It is as at least as important in rural and remote primary care as ACRRM, and because of its numbers it may even be more important. Surely having the RACGP as a member is going to help this PHN with duties in managing primary care in the region.

So why hasn’t it happened after 18 months of trying?

Any stalling at the NQPHN looks like it could be politically driven by the directors (and quite probably, the members).

Hopefully the Department of Health review will look at why the NQPHN has seen fit to block the largest GP representative body in the country from being a part of the organisation, when it is supposed to have primary care as its core focus.

The constitution of NQPHN allows for power imbalance in management

If you look at the current and past members of NQPHN, you could easily ask a few questions on the potential for member bias, if this organisation is really meant to be all about primary care.

Of the current 11 members of the organisation, four are regional Queensland government hospital groups, commonly referred to as an HHS (Hospital and Health Service). In fact, every HHS in the region is a member.

You might explain this away by pointing out that, of course all HHSs should be there as the task of a PHN is to help vertically integrate patient care by making primary care more seamless and relevant to the tertiary care sector through initiatives such as population health data analysis.

That’s fine.

But if your constitution then gives equal voting rights to members, as the NQPHN does, without any recourse to the problem of member imbalance, you’re likely to end up in trouble at some point.

In terms of the constitution and shareholder (member) voting rights of NQPHN, the organisation is effectively controlled by the local hospital sector, not the primary care sector.

Until a few years ago, NQPHN only had eight members, and four of them were HHSs.

Today that figure is 11 total members, but the power of that initial hospital block of members stands, even with 11 members, because the remaining seven members, aren’t naturally aligned in any block that could oppose the HHSs in a vote – ACRRM, the Pharmacy Guild, Aboriginal Health Services, et al.

Which means the NQPHN constitution, the foundation upon which the whole organisation is run, is possibly, fundamentally flawed.

Which raises a very big question for all of Australian healthcare: How many other PHNs have histories and constitutions that may not actually be fit for purpose?

PHNs are eclectic in foundation, governance and management

Historically, PHNs were once organisations that were almost entirely devoted to helping GPs – divisions of general practice. But over time the DoH significantly migrated their focus and purpose through their evolution to Medicare Locals and finally as PHNs, to a point where the main client might be said to be disadvantaged patients, not GPs.

In theory, the remit provided to PHNs by the DoH is a great one: work with all parts of the primary care community to build better integrated care for all patients, in particular ones that might lie beyond even the GP networks.

But what about in practice?

Who is measuring the performance of PHNs against the key performance indicators they have been set by the DoH?

In 2018, the DoH established a “Performance and Quality Framework” program for PHNs in some attempt to bring cohesion across the sector in terms of purpose and performance.

At the highest level, the DoH set broad program objectives for PHNs and some priority areas, and then said that there would be obvious variance in emphasis depending on what region a PHN was serving.

But none of this has been implemented, probably in part due to the interruption of covid.

The Mallacoota incident

If you’ve been watching People’s Republic of Mallacoota on the ABC, you might get some sense of how the dynamics of community can unfold in a remote Australian country town.

Nothing is easy.

In Mallacoota, there is only one GP practice, serving just over 1,000 permanent residents (although in the tourist season the number of people the practice serves can swell to several times this number).

With such a small, remote and itinerant population problem, the local GP practice has struggled over the years to maintain a consistent service for the locals.

In 2016, down to just one doctor, and desperate to retain at least the daytime service for the local community, the practice had to cease providing after-hours services.

Notwithstanding that, the local practice owner pleaded with various authorities for help.

She pointed out that without any after-hours help, a resident might have to travel four hours to the nearest health provider if they needed antibiotics or wound care.

At that time, the Victorian Health department responded by saying that emergencies in the town could be handled by ambulances, so an after-hours service was not needed.

In January 2019 the town suffered catastrophic fires, and subsequently mental health became a much bigger local issue for the town.

Then the pandemic hit.

According to the local GP, there is a paramedic roster in town now since the fires that they need to hold on to, and with that now in place, a co-ordinated after-hours model could easily fill the gaps and bring Mallacoota in line with the rest of Victoria in terms of that sort of service.

In 2021, Gippsland PHN, the headquarters of which are 350km away and more than a four-hour drive, put out a tender for after-hours services for Mallacoota and the surrounding area.

The local GP practice, seeing the opportunity to employ a couple more local healthcare workers to deliver a local service which had continuity with the local practice, was the only group to tender for the $100,000 contract.

But when the tender closed, Gippsland PHN did not award the tender to the local practice in Mallacoota.

Instead, they reissued the tender, and within a short time-frame they somehow had a tender from a corporate telehealth-based doctor service out of Sydney.

They awarded the tender to the Sydney telehealth operation, which employs ED physicians, not GPs, and which has until now had most of its business focus on filling in the holes in emergency departments in hospitals big and small across the country, not in running rural and remote GP after-hours services.

Mallacoota is an unusual local set-up. It is very remote, without access to health centres or a local hospital. It’s feasible that the GPHN considered this in its deliberations, so felt an ED-based after-hours telehealth operator was appropriate.

But according to Mallacoota residents, very little regard was given to what the locals wanted, and how the locals would utilise the resources to optimise their own healthcare needs.

Certain concerned residents of Mallacoota have since written letters to the DoH asking for documents that might explain on how legally GPHN extended the tender, and why the tender from the local GP practice was rejected, given the obvious advantages that an on-the-ground GP practice presence with more staff and continuity of care for local residents might provide.

So far, those residents have had most of their requests denied, and most recently most of a Freedom of Information request was rejected by the DoH on the grounds that it contained too much personal and business information, and that it wasn’t in the public interest.

Whose public interest, you wonder?

Certainly not the residents of Mallacoota, as they remain in the dark over how a PHN could warp a tender process in a manner that looks from the outside as one against observed public service tender protocol, fail to engage meaningfully with the local community and GP practice on such an important funding allocation, and then get stonewalled by that PHN and the DoH.

You don’t like to play the bushfire, mental health and pandemic card, but in the case of Mallacoota, you almost certainly should. It’s yesterday’s Lismore.

This is a town still in a lot of distress that deserves some special attention, no matter how small and remote it is.

The question for most of the local residents, and the hard-working long-time owner of the local Mallacoota GP practice, is a pretty good one: on what grounds did a PHN award a $100,000 contract to a remote telehealth-based corporate group out of Sydney over a long-term, locally owned and run community GP practice, for providing after-hours services in the town?

Why and how does a PHN get to decide how to spend $100,000 in Mallacoota when that PHN is geographically vastly distant from where the service in question needs to be implemented, has not involved itself much in running any services that meet the profile of the town and has refused to engaged in a meaningful manner with any of the concerned local residents or the local GP practice?

The local GP has said about the situation that “Mallacoota has access to three highly trained rural general practitioners and a further six or so nurses who are locally available. However, none are employed, as there is no healthcare institution no local urgent care facility no regional health service and no bush nursing”.

“Without the [funding and] ability to employ a single in-situ clinician on the ground, it is obvious that [a remote telehealth] model is not fit for purpose, safe or appropriate?within the Mallacoota context,” the GP said.

PHNs are privately run companies that the DoH claims are free to develop strategy and make decisions on local health funding, within the overall framework set for them by the DoH.

But like NQPHN, it looks like the privately constituted nature of GPHN may have led to issues with governance and performance against such a framework that the DoH has been unable to monitor closely enough.

Partly why the DoH can’t monitor things is that every PHN has been built up privately in its own way, often with quirks in its own constitution and member duties. Each has unique local issues, especially rural and remote PHNs. We aren’t talking about a uniform set of organisations with a uniform set of rules or even performance criteria.

NQPHN is a not a one-off of the sort of problems that are occurring in certain PHNs as a result of their eclectic histories and upbringing.

GPHN has been accused by some residents of Mallacoota of having similar issues of conflict that the chairman of NQPHN has had, and possibly worse.

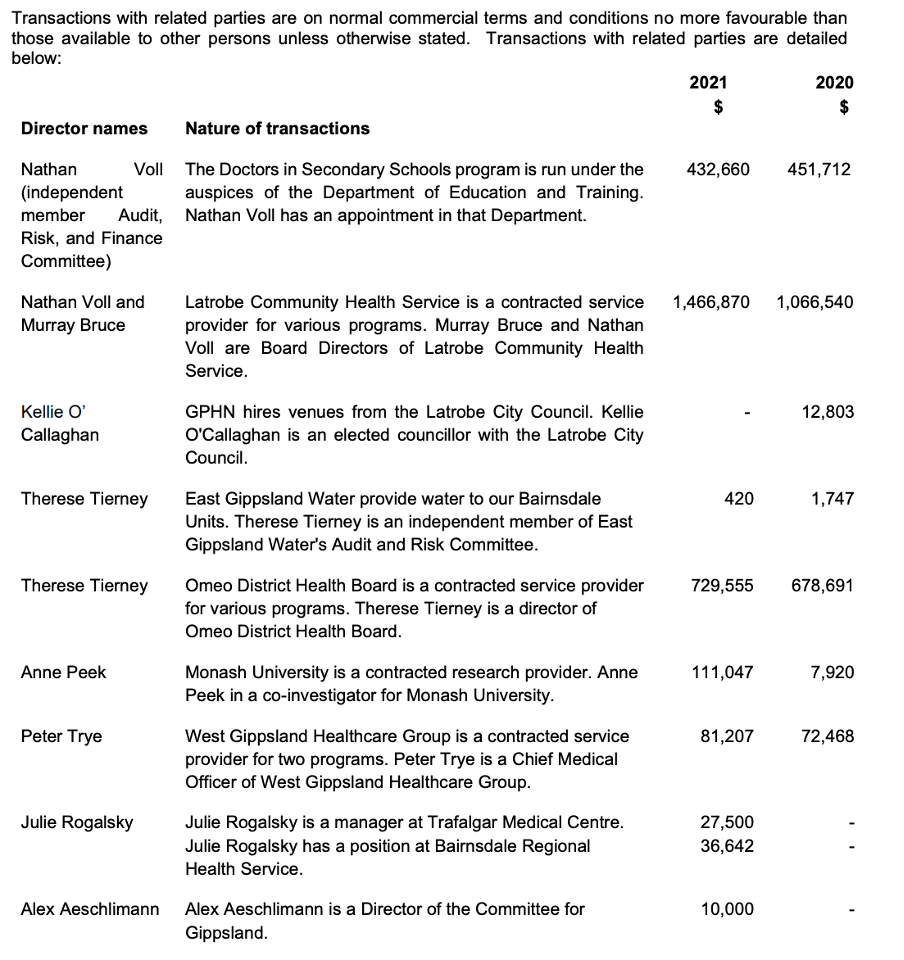

If you look at GPHN’s latest annual report, what immediately strikes you is the note on transactions with related parties. Per NQPHN, the report claims the transactions “are on normal commercial terms and conditions no more favourable than those available to other persons unless otherwise stated”.

All in all, nine directors of GPHN are involved in related party transactions that total $2.784 million, almost 10% of the entire funding of that PHN. The entire list, including which director is in potential conflict, is reproduced below. Notably, the residents of Mallacoota are upset that the chairman of the PHN is also a director of the health service based in Omeo, which is a similar-sized town, which won a contract for almost $730,000.

None of this necessarily indicates, and we are not implying, impropriety on the part of any of the directors of GPHN.

But without a decent detailed audit showing how each of these transactions are either arm’s length or on terms no more favourable than a normal commercial contract, who could blame the residents of Mallacoota for being suspicious that something is amiss?

After all, the chairman of the PHN, who awarded Omeo District Health Board a contract for almost $730,000, is also a director of that health board, and the residents of Mallacoota and their GP practice owner did not get a look-in on a $100,000 contract that had the potential to significantly bolster their local health services, and provide local employment to a community in severe distress.

Without some investigation and proper explanation into what happened on the tender, for which the Mallacoota GP practice was originally the soul tenderer, how could the residents of Mallacoota feel comfortable that everything was above board?

By reading a sparse annual financial report that has boiler-plate financial officer and auditor promises that everything is hunky dory?

There is no publicly available audit of either the GPHN accounts or the NQPHN accounts that is able to definitively prove to outsiders that the boiler-plate statements in their financial reports that all these contracts were arm’s length, or at normal rates, is true.

That is not to say that such reports don’t exist anywhere or the auditors didn’t do detailed checking. But if they do, given the issues at hand, why are they not easily publicly accessible?

Given the issues at hand in terms of conflict revealed at NQPHN, surely someone has to check this now.

If they don’t exist, clearly now the DoH has a very big issue of trust emerging in the governance of some PHNs that is likely to taint the whole network.

The PHN network around Australia is a vital linchpin in the government’s strategy to manage care into the community, with an important part of that strategy being effective integration with general practice.

The problems at NQPHN and GPHN, the failure of the DoH to stand up its performance framework for PHNs, the lack of transparency around all PHN reporting, and the eclectic history of the foundation of these privately constituted entities, are starting to erode community trust in the whole set-up.

Open letter from Dr Nicole Higgins on her resignation from NQPHN

I recently resigned from the board of NQPHN. This left NQPHN in breach of its constitution with no GPs on the board. I was the second GP to resign within the space of a couple of weeks. It triggered a departmental review into the governance of NQPHN and has shone the spotlight on the relevance of PHNs to general practice who are the largest providers of primary care.

The governance review is part of the fallout from the Nth Qld Pharmacy Scope of Practice Pilot where a lens was shone on issues around governance, the structure and purpose of PHNs and the influence of members on decisions. I am disappointed that the findings will not be made public as the lack of transparency and management of conflicts is what triggered the department to step in.

I resigned because of the poor governance decisions and values that were no longer aligned. At the same time, local GP’s formed the NQ Doctors Guild, a group of 250 doctors who were also concerned about the direction and performance of their PHN.

The problems:

- Governance. There is currently a federal government review of NQPHN governance, and I call for openness and transparency and the details to be published. The current issues are around management of Conflict of Interest (COI). North Queensland is a big small place and people wear multiple hats in different organisations so managing conflicts of interests seems to be difficult.

- Influence of Members. Members appoint the board to govern. In NQ, the lines have been blurred. The members influence decisions and expect that substantive decisions such as withdrawal from the pilot be run past them first for their approval. In other circles this could be considered shadow directorship. The members of influence of the NQPHN are the 4 local HHS (Hospital and Health Services) and the Pharmacy Guild.

The PHN is viewed as a funnel for federal money into North Queensland. That is not a problem if one is trying to maximise the funding impact but when it is supporting their own aims it becomes an issue. It is a tangled web of influential organisations, institutions and relationships.

The RACGP had been trying to become a member of the NQPHN for 18 months, however its membership application continues to be delayed.

- Purpose of PHNs. 90% of our community have a family doctor and GPs represent the biggest group of providers delivering primary care. There is a perception from external stakeholders that PHNs represent general practice. They don’t. This week we heard that Gippsland PHN has given funding to an external corporate afterhours telehealth provider instead of the local general practice who would provide face to face care. In North Queensland, GP’s do not feel valued and disengaged with the PHN after a similar afterhours issue a couple of years ago. For local GP’s who were already disenfranchised, the North Queensland Pharmacy Scope of Practice pilot and the perceived influence of the Pharmacy Guild on the PHN was the last straw.

Knowing where you can best add value – inside or outside the tent is the key to having influence. Most of the time it is inside the tent. If I could have solved this quietly inside the tent – I would have. Taking a stand and putting yourself out there knowing that the consequences of your decision affect others such as employees etc. was challenging. There are some excellent and ethical board members on NQPHN and the people on the ground are doing a wonderful job.

I urge the federal government to make the review of NQPHN open and transparent to ensure that our communities can have faith that taxpayers money is being invested in their healthcare appropriately.

What I witnessed was the power of grassroots GPs and the power of conversations. North Queensland GPs have come together over this issue in a way that shows me how strong we can be when we all walk in the same direction. This issue has transcended our representative organisations and siloism and has started a bigger conversation.

PHNs don’t represent GPs.

We do. Us.

Dr Nicole Higgins