Recognising complicated-grief reactions is critical for deciding on appropriate therapeutic intervention

That we will experience loss at some stage in our lives is almost a certainty. Grief is often described as a process of departure from our usual state of health and wellbeing, which requires time to heal.

Grief evolves over time, with the bereaved experiencing a variety of psychological and physiological symptoms. It is strongly influenced by socio-cultural norms regarding the appropriate intensity of, and place for, emotional expression following a loss.

Most individuals will come to accept the finality of a death, including its consequences, and will redefine their life goals while adjusting to the world without their loved ones. Grief does not only occur in the case of death; it is a common experience in situations such as job loss and divorce, as well as in patients who develop severe illness.

Each person’s loss is unique, and due to circumstantial and relational factors, grief presents differently in each person, or may be the result of comorbidities. A complicated grief reaction occurs when an individual continues to remain in a state of grief. This has been associated with a wide range of adverse effects on physical health, including heart disease and hypertension.

Loss and identity

Death of a loved one can lead to an altered lifestyle as well as lead to concurrent changes in personal identity of the bereaved. The ability of an individual to make and adjust to changes to life goals following a loss can affect the speed of recovery following the loss of a loved one.

Literature surrounding loss and identity has also highlighted the association between grief resolution and an individual’s ability to adapt their self-identity following a loss.

A positive correlation exists between complicated grief and inclusion of the other in self-identity, particularly the degree to which character traits of the partner are treated as one’s own. This inclusion of the other in self-identity is known as self-expansion.

In addition to this, individuals whose self-identifying memories involved the deceased may show higher rates of complicated grief.

Therefore it is useful for clinicians to focus on shifting perceptions of the patient’s self-identity away from the deceased, perhaps by implementing strategies to develop an alternative goal focus for themselves.

This is particularly difficult in couples when self-identity becomes blurred by what is known as “relationship diffusion” , which becomes important when understanding complicated grief related to spousal death.

Contributing factors

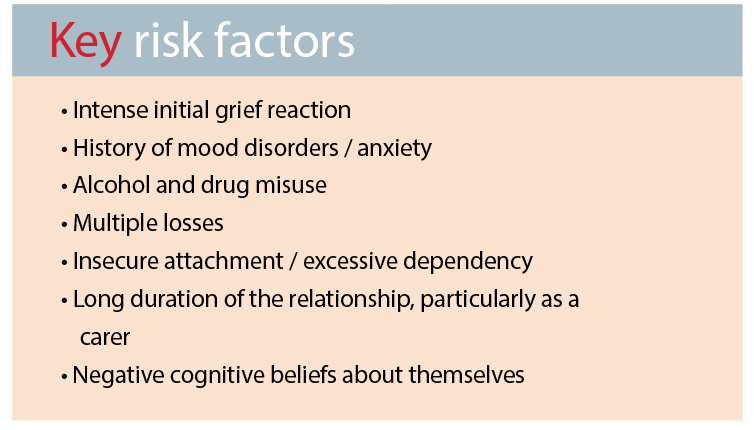

Directly following a loss there is a state of heightened arousal, which may delay the start of the grieving process. Therefore, intense or pronounced initial grief reactions could be a marker for complicated grief as this state delays the onset of normal grieving more than would normally be the case. The amount of time that this intense state continues after the loss is also a distinguishing factor in leading to abnormal grief reactions.

A history of mood and anxiety disorders, alcohol and drug abuse and multiple losses are all additional risk factors for complicated grief.

Circumstances surrounding the loss, along with the nature of the relationship with the deceased, can be linked to higher levels of attachment-related anxiety and over time contribute to complicated grief reactions.

It has been found that people with anxiety disorders are more susceptible to becoming fixated on the loss, and this has been linked to the later development of clinically significant mood and anxiety disorders. We know that attachment anxiety is a predictor in grief severity, with individuals who score highly in attachment anxiety using objective measures such as the Adult Attachment Scale tending to experience more severe grief.

Affective bonds with the deceased are weaker for those individuals who display avoidant-type behaviours, which may lead them to grieve less. On the other hand, insecure attachment style and excessive dependency on the deceased in particular, is predictive of prolonged abnormal grief reactions. The amount of time spent with the deceased in the period before their death significantly increases the risk of complicated grief. This indicates two possibilities; that more time spent with the deceased facilitates a stronger bond or level of attachment, or that the amount of time spent caregiving for the deceased prior to death may be a contributing factor towards complicated grief. Therefore, patients or others who share a close bond with an individual who is terminally ill are also at risk of grief reactions.

Health professionals who have bereaved clients with higher levels of grief severity could discuss the possible presence of a high level of attachment anxiety and the importance of addressing this in order to seek resolution.

This discussion may influence the nature of treatment that is most acceptable, both to encourage engagement and also for the best outcome.

Treatment

Currently, there is insufficient evidence to adequately guide appropriate treatment for those with complicated grief. As a result, people with complicated-grief reactions have often been treated with options more suited for depression and mood disorders.

However, research suggests that if medication is used, it should be in addition to psychological interventions such as CBT.

It is also likely that matching therapeutic interventions to the attachment orientation of the bereaved individual is more likely to be effective. For example, benefit may be gained by using bond-enhancing procedures such as review of photographs or writing letters to the deceased or through bond-de-emphasising interventions such as saying goodbye or revising life goals.

Cognitive factors in the bereaved, such as holding a negative belief about themselves, their life and the future, is strongly linked to grief severity, perhaps because of the coping abilities of the individual.

On the other hand, dispositional factors such as active coping, optimism, support-seeking, positive reframing, and perceived social support may lower the risk of complicated grief after the loss of a loved one.

Thus, interventions that encourage a positive outlook as well as strengthening active coping skills are likely to be useful.

The therapeutic area of bereavement counselling is located within a climate of ongoing questioning and debate due to the progressive development of important grief-related constructs and new models of mourning.

The growing conceptual understanding of complicated grief holds promise in terms of facilitating accurate and objective diagnoses, and the development of specific and effective therapies.

Identifying individuals who are anxiously attached, or have a history of other risk factors surrounding self-identity, can help detect those with complicated grief, and guide appropriate therapeutic intervention.

Ruby Myers is a counsellor on the northern beaches of Sydney. Her master’s thesis focused on complicated grief and factors affecting the grieving process

References available on request