Recent clinical advances and guidelines provide a standardised approach for this pre-malignant condition

More than 1300 people are diagnosed with oesophageal cancer in Australia each year, making up 1.4% of cancer cases in men and 0.8% of cancer cases in women.

But while the cancer is still relatively uncommon, the incidence of adenocarcinoma of the oesophagus in Australia is increasing.

Patients are often asymptomatic until the tumour has grown to be inoperable, and long-term survival for this cancer remains poor, with a five-year survival rate of 25% for those who present with local or nodal disease and rates lower than 4% for those with metastatic disease.

Less than 40% of patients can be offered potential curative therapy at the time of diagnosis, so early diagnosis is crucial to improve survival.

Barrett’s oesophagus is a pre-malignant condition, which, if identified and treated, can prevent the development of oesophageal cancer. However there has been controversy internationally as to the most appropriate way to identify and treat this condition.

Recent clinical advances and guidelines should help to standardise management and improve outcomes.

Barrett’s oesophagus was named after Dr Norman Barrett, who described the potential significance of columnar epithelium in the distal oesophagus. He was born in Adelaide, South Australia in 1903 into a family of doctors (his uncle, Sir James Barrett was a founder of the Royal Australasian College of Surgeons). He moved to the UK at the age of 10 and was educated at Eton and then at Cambridge University before ultimately becoming a thoracic surgeon at St Thomas’s Hospital in London, where he became an authority on disorders of the oesophagus.

Barrett’s oesophagus describes the metaplastic change of the squamous epithelium that normally lines the lower oesophagus into columnar epithelial cells.

The condition is thought to arise secondary to chronic inflammation in the distal oesophagus related to gastro-oesophageal reflux disease (GORD), and can also be associated with hiatus hernia, smoking, and central obesity. Alcohol does not seem to be an independent risk factor for Barrett’s oesophagus. It is seven times more common in males, especially over the age of 50 years, and is thought to have an inherited predisposition. Being overweight and male are also associated with an increased risk of progression of Barrett’s oesophagus to cancer.

In Australia, a diagnosis of Barrett’s oesophagus is made only if intestinal metaplasia of oesophageal epithelium is present with other forms of columnar epithelium not thought to confer an increased risk of progression to cancer.

It is thought that the potential development of cancer arises from the progression of normal oesophageal epithelium to intestinal metaplasia, before further change to dysplasia and ultimately adenocarcinoma.

The majority of patients with Barrett’s oesophagus are identified when undergoing a gastroscopy for symptoms of difficult to treat reflux disease, or for red-flag symptoms, including unexplained weight loss, dysphagia, persistent vomiting or iron deficiency anaemia.

Diagnosis is made on the basis of visualisation of changes in the distal oesophagus extending beyond a length of 1cm, along with histological confirmation.

The Prague classification system is used to standardise diagnosis and reporting of Barrett’s oesophagus by defining the length of columnar mucosa above the gastro-oesophageal junction. The circumferential (C), and maximum extent (M) of endoscopically visible columnar-lined together with any islands are also documented. This classification is key to determining the appropriate management and surveillance intervals of patients.

SCREENING

Endoscopic screening in the general population is not currently recommended as no benefit has been found. Globally, the prevalence of Barrett’s oesophagus is less than 5%, but may be as high as 15% in high risk groups – focused screening can therefore be considered in patients with chronic gastro-oesophageal reflux (GORD) symptoms and multiple risk factors (at least three of age 50 years or older, white race, male sex, obesity).

However, the evidence for benefit even in this group remains limited. If there is a family history with at least one first-degree relative with Barrett’s oesophagus or oesophageal adenocarcinoma, screening may also be considered at a lower threshold.

Transoral endoscopy is the gold-standard technique for the identification and surveillance of Barrett’s, however, transnasal endoscopy using ultra-thin scopes has also been investigated and recently been proven to be an accurate and well-tolerated alternative for screening. This may have advantages in trials of future screening programs in terms of cost and comfort levels.

Another potential non-invasive diagnostic test is a non-endoscopic capsule sponge device, which is a small mesh sponge attached to piece of string which is swallowed and used to retrieve oesophageal cells for analysis of biomarkers associated with Barrett’s e.g. Trefoil factor 3 immunohistochemistry (TFF3).

Again, though this may confer some advantages as a simple screening test in community settings and has initial promising results, the evidence is yet insufficient to recommend its use.

Endoscopic screening in the general population is not currently recommended as no benefit has been found.

SURVEILLANCE

The aim of endoscopic surveillance is to detect cancer or pre-malignant changes in patients with Barrett’s oesophagus at a stage when intervention may be curative. The approaches to surveillance have varied around the world and over time, as there have been no high-quality, randomised controlled studies to definitively guide the process. However, data from cohort studies have suggested an improved outcome with surveillance, and recent guidance has aimed to standardise endoscopic practice.

Endoscopy is performed using high resolution equipment, with routine biopsies taken at every 2cms throughout the Barrett’s segment (Seattle protocol). Targeted biopsy of any focal lesion is also performed. The aim is to confirm intestinal metaplasia (i.e. a diagnosis of Barrett’s) and to identify early histological changes of dysplasia within the affected area. This dysplasia is also categorised as low or high grade, which again affects further management.

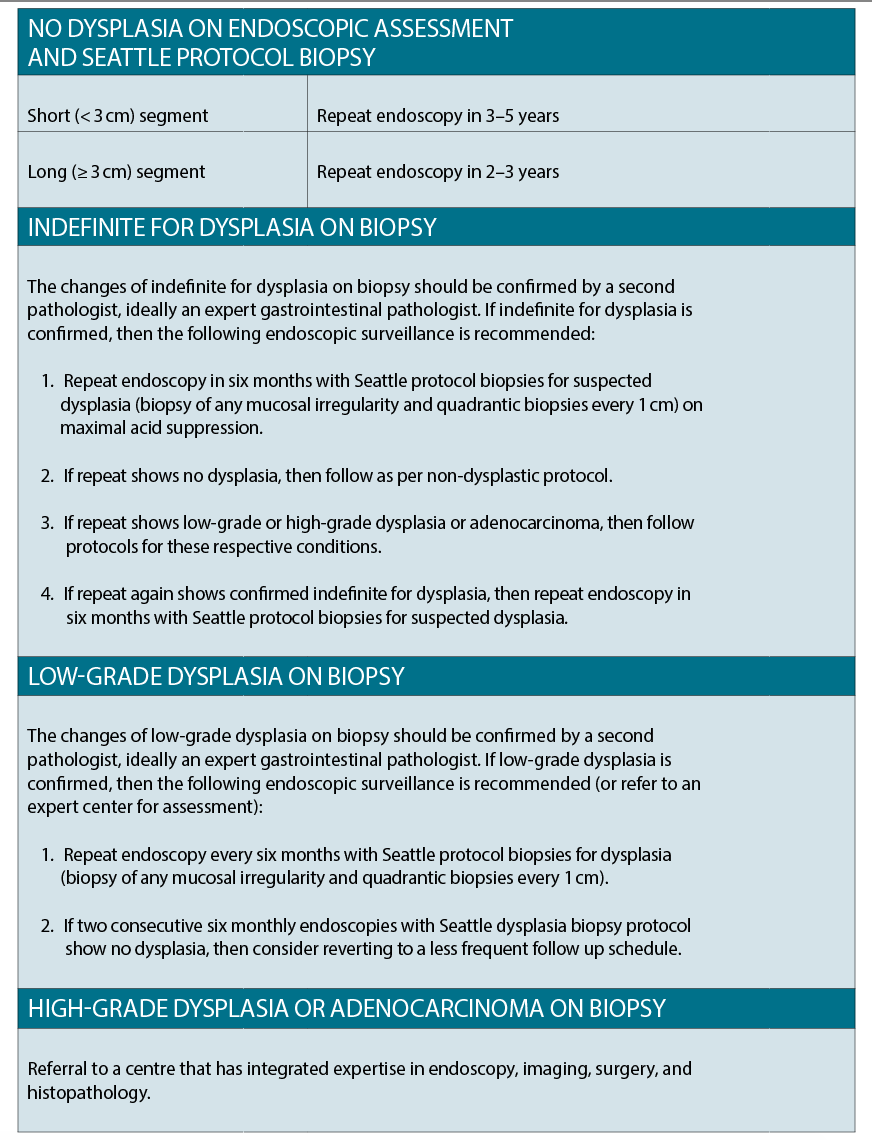

The frequency of surveillance gastroscopies is predominantly determined by the length of the affected segment and the nature of the histological findings (See table right).

Patients should have an initial discussion about the pros and cons of surveillance, including the risks of the procedure and potential failure to prevent cancer. As there are now more non-surgical options for early oesophageal cancer, it isn’t necessary to restrict surveillance to patients fit enough to undergo oesophagectomy. However, the patients’ life expectancy should be long enough that they would benefit from the detection of an asymptomatic oesophageal tumour.

While surveillance in appropriate patients is thought to improve outcomes, and reduce oesophageal carcinoma development, there is a huge variation in the literature about the cost benefit, with results varying from cost-effective to highly cost-ineffective. More work is needed to determine whether changing the criteria for who undergoes surveillance will improve cost effectiveness.

DYSPLASIA MANAGEMENT

Dysplasia is the neoplastic transformation of the epithelial cells that line the oesophagus, confined and localised within the basement membrane. The degree of dysplasia identified on histological examination of the tissue is graded into four categories – negative, indeterminate, low-grade and high-grade.

A degree of variability can occur in the pathological reporting of the cell changes, and therefore it is widely recommended that any diagnosis of indeterminate, low or high-grade dysplasia should be reviewed by at least one expert gastrointestinal pathologist.

Recent guidance endorses endoscopic therapy over oesophagectomy or endoscopic surveillance for high-grade dysplasia and mucosal adenocarcinoma. Therefore, repeat endoscopy should be carried out by an expert endoscopist to detect any focal lesions within the Barrett’s and assess suitability for endoscopic resection. Endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR) has the dual role of staging a potential tumour, both in terms of the depth of the lesion and also in confirming the diagnosis, as there is a reasonable risk of sampling error from biopsy alone.

Up to 50% of patients identified as having high grade dysplasia or cancer using endoscopic mucosal resection will have had an inaccurate biopsy result. Endoscopic mucosal resection is also used as a therapeutic procedure and for determining whether further therapy will be required. Positron Emission Tomography – CT (PET-CT) and Endoscopic Ultrasound may have an additional, but limited, role in the assessment of high grade dysplasia and mucosal cancers.

Endoscopic resection of dysplastic lesions and carcinomas confined to the mucosa is a generally safe procedure, particularly when compared with oesophagectomy, though it can be associated with stricture formation if large amounts of circumferential tissues are removed, as well as bleeding and perforation.

Various techniques are available, including endoscopic mucosal resection and submucosal dissection, and technological advances continue, allowing a wider range of lesions to be treated more easily. Resection and retrieval of a focal lesion endoscopically allows histological assessment of the depth of neoplastic invasion and completeness of excision.

If the patient has dysplasia or an early mucosal cancer only, there is a very low risk of lymph node involvement, and endoscopic treatment should be planned as definitive therapy. The presence of submucosal involvement on the resection specimen even if completely resected is associated with potential local nodal involvement and surgical assessment should be undertaken.

If all visible lesions are resected endoscopically, there will be residual flat Barretts that many harbour dysplasia or be at risk of developing further neoplasia, which should be ablated.

Although there are a variety of techniques including photodynamic therapy, cryotherapy and argon plasma coagulation, the most commonly used is radiofrequency ablation. This uses either a circumferential or focal electrode to deliver high frequency energy to the lining of the oesophagus causing superficial tissue damage but leaving deeper layers intact, thus minimising side effects.

Treatment is performed as a day case, but involves a number of sessions over a period of months to achieve resolution, followed by ongoing surveillance even if resolution has occurred.

Side effects include short-lived dysphagia and discomfort, and uncommonly oesophageal strictures, which can usually be treated using endoscopic dilatation.

Response rates exceed 90% for dysplasia and are durable on follow up for five years but patients should be followed up with surveillance as localised recurrences can still occur and can be still successfully treated endoscopically.

Cryotherapy is a novel technique using liquid CO2 delivered endoscopically onto dysplastic epithelium causing local tissue ablation.

This technique is still being evaluated and is used mostly in small areas of residual disease after other ablative techniques have been attempted. Argon Plasma Coagulation is an older, widely available technique that is useful for small areas of residual Barrett’s.

Previously, low-grade dysplasia has been monitored with intensified surveillance protocols for evidence of progression to more advanced neoplasia.

Recent data suggests that this may carry a significant risk of malignancy developing and hence if low-grade dysplasia is confirmed at repeat gastroscopies, endoscopic ablation may be considered. This is an individualised decision, based on the discussion of risks and benefits with the patient.

Another potential non-invasive diagnostic test is a non-endoscopic capsule sponge device.

MEDICAL TREATMENT

Most guidelines recommend once-daily treatment with a proton pump inhibitor (PPI) for all patients with Barrett’s oesophagus. Most will already be on treatment for symptoms of reflux but rather than attempting a “step-down approach” based on symptoms as with reflux, ongoing treatment is needed.

This is based on several cohort studies that suggest the risk of progression of Barrett’s oesophagus to cancer is reduced among patients taking maintenance PPI therapy.

Other drugs that may decrease the risk of progression to oesophageal adenocarcinoma include non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, aspirin, metformin, and statins.

Currently the risk versus benefit of treatment is not defined, and routine use of these drugs is not recommended. Results from a large trial looking at concurrent use of aspirin and PPIs in Barrett’s oesophagus are awaited.

As with all patients with reflux, lifestyle modifications, including weight loss and bedhead elevation can be helpful.

Young patients who are likely to require life-long treatment or those with difficult to control symptoms may also benefit from referral to a specialist for consideration of antireflux surgery. However, antireflux surgery may make Barrett’s oesophagus surveillance more difficult because of the postoperative anatomy.

Dr Neil Kapoor is consultant gastroenterologist at Aintree University Hospitals, NHS Foundation Trust in the United Kingdom

References available on request