This is a problem for a quarter of mid-life women, but one with many solutions.

Heavy menstrual bleeding (HMB) is defined as excessive menstrual blood loss that adversely interferes with the physical, emotional, social and/ material quality of life.

It affects about 25% of women of reproductive age. The more research-based, traditional definition is menstrual loss of more than 80mL/cycle, though this is obviously less practical to quantify in a clinical context.

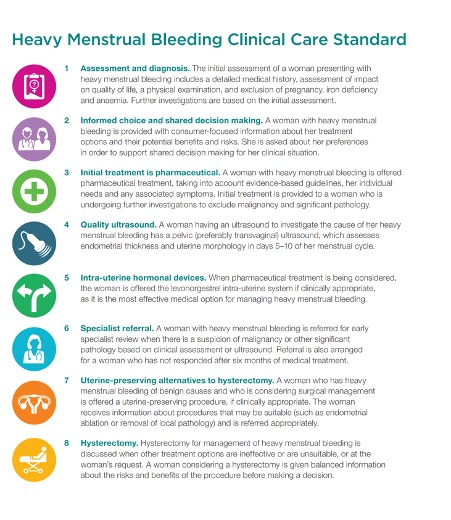

The Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care has published new national HMB standards, with an aim to streamline and improve women’s health across the country, for this common but under-recognised condition.

This document covers the spectrum of care provided to women, from primary care settings, family planning and sexual health services, public gynaecology clinics and private specialist practices, to hospitals and radiology sites.

There are many effective treatment options for HMB. I typically start the consult discussion by sharing that “this is a problem with many solutions, let’s work together to create a management plan most suitable for you”.

About half of women with HMB report significant co-existent pelvic pain. There can also be symptoms related to iron deficiency anaemia as well as anxiety around menstrual hygiene and managing the heavy vaginal loss.

The majority of patients with HMB can be looked after effectively by their general practitioner. This process starts with a solid history and thorough assessment, and is helped by proactively sharing relevant patient resources and by an appreciation of the woman’s treatment goals.

Assessment should include both a diagnostic and a therapeutic angle. The factors to consider include:

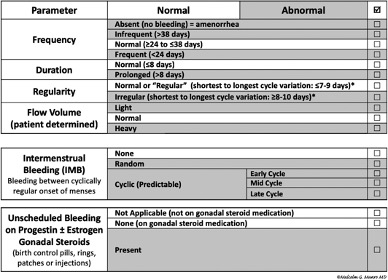

- How heavy is the bleeding? Are the cycles regular? Prolonged? Painful?

- Are there any symptoms suggesting a bleeding disorder or hypothyroidism?

- What is the desire for fertility?

- Is there a preference for medical options including hormone-based management?

- Or a preference for surgical options of care?

- Are there any associated perimenopausal symptoms?

- Are there symptoms of anaemia, such as tiredness, fatigue or shortness of breath?

Essentially, during perimenopause there is an increased percentage of anovulatory cycles and hormonal imbalance, making women more likely to experience abnormal uterine bleeding.

The possibility of underlying uterine malignancy must be considered. It is indeed the most common gynaecological malignancy in the Western world.

Women are at an increased risk of developing uterine cancer if they:

- Are over the age of 45 years

- Have a high BMI

- Have never had children

- Have a background of polycystic ovarian syndrome

- Have a family history of endometrial, ovarian or bowel cancer

- Have type 2 diabetes

- Use unopposed oestrogen or tamoxifen

- Have endometrial hyperplasia, which is defined as irregular proliferation of the endometrial glands and is three times as common as endometrial cancer.

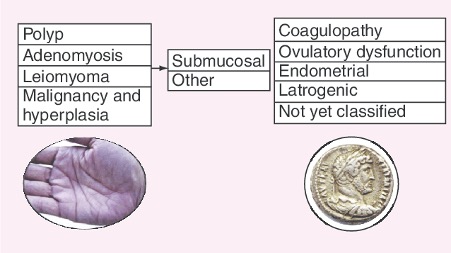

The FIGO ‘PALM-COEIN’ classification of possible causes of abnormal uterine bleeding, is an acronym that stands for polyp, adenomyosis, leiomyoma, malignancy, coagulopathy, ovulatory dysfunction, endometrial, iatrogenic, and not-yet-classified as causes of abnormal uterine bleeding in the non-gravid woman.

About 30% of women with HMB have fibroids, and about 10% have polyps.

I find the Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care’s Clinical Care Standard from 2017 helpful:

I have also found the RANZCOG Heavy Menstrual Bleeding pamphlet helpful, and we give women both this and the Heavy Menstrual Bleeding Clinical Care Standard – consumer fact sheet. Together, they provide empowering information that enables the woman with HMB to actively contribute to her management plan.

Investigations

- Ensure the cervical screening test is up to date. Remember that women with symptoms (especially intermenstrual bleeding, post-coital bleeding and post-menopausal bleeding) that suggest cervical cancer need diagnostic testing rather than just screening – that is, a co-test and gynaecological assessment.

A co-test is where the laboratory tests for both human papillomavirus (HPV) and liquid-based cytology (LBC) on the sample collected.

It is not necessary to request a co-test or refer for a colposcopy if a patient has2:

- breakthrough or irregular bleeding due to hormonal contraception

- contact bleeding that occurs when collecting a cervical sample

- heavy regular periods (menorrhagia)

- irregular bleeding due to a sexually transmitted infection (STI) such as chlamydia.

- Blood tests checking for anaemia, iron levels and thyroid disease may be useful in the HMB work-up.

- A high-quality pelvic ultrasound, including transvaginal ultrasound, can be used to detect structural abnormalities in the uterus including fibroids, polyps and adenomyosis. The best time to do a pelvic ultrasound is from day 5 to day 10 of the menstrual cycle. This allows the endometrial lining to be naturally thinner, allowing any endometrial polyp or submucosal fibroid to be easier to visualise.

- A hysteroscopy and endometrial biopsy

Treatment options

Initially, offer medical interventions

In order of evidence of effectiveness and adverse effects:5

• Levonorgestrel-releasing intra-uterine system (LNG-IUS)

• Tranexamic acid or non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) or combined oral contraceptives

• Cyclic norethisterone or injected long-acting progestogens.

LNG-IUS is a popular first-line therapy, effective for about 80% of women with HMB (without significant identified uterine pathology) and may avoid surgical intervention, over the next 5 years.

It can be used for women with fibroids less than 3cm in diameter that are not causing distortion of the uterine cavity or suspected or diagnosed adenomyosis.5

It is important to appreciate that the LNG-IUS ideally should be inserted from day 1 to day 7 of the menstrual cycle, as the cervical os is ever so slightly open during this time, making it technically easier, and of course minimising the risk of an unintended pregnancy.

It is critical to counsel the patient to expect some changes in bleeding pattern, including intermenstrual bleeding and spotting, especially during the first three to six months. Studies suggest 80% of women report a reduction in bleeding by three months, and 20% are amenorrheic by one year.6

Tranexamic acid serves as a really good initial treatment option. Even if it isn’t totally satisfactory in terms of effectiveness or tolerability, it can at least be a Band-Aid while awaiting specialist review, to preserve the woman’s ferritin stores and minimise her risk of anaemia. Tranexamic acid has unfortunately not been consistently available during the COVID-19 pandemic in Australia.

Surgical management

Minimally invasive procedural interventions include endometrial ablation and the removal or destruction of polyps and/or fibroids using hysteroscopic or radiological techniques.4

Surgical management offers vision inside the uterine cavity (hysteroscopy) and endometrial biopsy can be obtained to get histopathological diagnosis of the endometrial lining. If the woman is significantly low in ferritin and a trial of oral iron replacement has been attempted, consider adding an iron infusion during that episode of care. Surgery may also include a myomectomy, if suitable, or a polypectomy.

Research has revealed that many women in Australia are not aware or not offered the option of these minimally invasive gynaecological procedures.

A hysterectomy should generally be considered the last-resort option for women who remain symptomatic despite all other treatments. As this is a procedure with risks, hysterectomy should be done only when well justified.

The Commission’s Australian Atlas of Healthcare Variation showed hysterectomy rates are up to seven times higher in some parts of Australia, especially in regional parts of the country, even though less-invasive treatments are available. There is also considerable variation in rates for endometrial ablation, with the rate of the procedure being up to 20 times higher in some areas compared with others.4

When to refer4 to a gynaecologist

- On detection of suspicious findings following clinical assessment or ultrasound (risk of malignancy increases with age, increased caution with >45-year-old group)

- If significant pelvic pathology, fibroids or polyps, suggested on pelvic ultrasound

- After a lack of effective response to medical treatment (if six months of optimal treatment has failed to reduce the PV bleeding)

- Some women may warrant earlier referral because of anxiety or preference

A word on international nomenclature

The International Federation of Gynaecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) published the PALM-COEIN classification system in 2011, to try to triage abnormal uterine bleeding (AUB) based on the likely underlying cause or pathology.

Previously used terms such as menorrhagia, menometrorrhagia, metrorrhagia, dysfunctional uterine bleeding, polymenorrhea and oligomenorrhea are no longer encouraged.

The FIGO based, PALM-COEIN system aims to standardise nomenclature to describe the severity and the aetiology of AUB.

I would like to invite you all to the upcoming and now virtual FIGO 2021 conference in Sydney, on 21-28 October. I am a track advisor and invited speaker at this and would be delighted to see you there – general practitioners are such an important part of women’s healthcare delivery in Australia.

Dr Talat Uppal is the director of Women’s Health Road and a clinical senior lecturer at the University of Sydney.

References

- https://www.rcog.org.uk/globalassets/documents/guidelines/green-top-guidelines/gtg_67_endometrial_hyperplasia.pdf

- https://www.health.gov.au/initiatives-and-programs/national-cervical-screening-program/providing-cervical-screening/managing-patients-with-symptoms-of-cervical-cancer#diagnostic-testing

- https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng88/chapter/Recommendations#investigations-for-the-cause-of-hmb

- https://www.safetyandquality.gov.au/sites/default/files/migrated/Heavy-Menstrual-Bleeding-Clinical-Care-Standard.pdf

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Heavy menstrual bleeding: assessment and management. Clinical guideline (update). London: NICE; 2016. Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg44/resources/heavymenstrual-bleeding-assessmentand-management-975447024325

- Mirena Consumer Medicine Information, dated October 2018