Writing and drawing helped this GP cope with an unbearable loss when talking couldn’t.

Here is an unpleasant fact of life: if you haven’t already lost a loved one, at some point you will.

And grief – well, let’s be honest – it’s a bit of an asshole. It pops up randomly and reduces you to a dysfunctional, leaky mess. Sometimes it makes you want to smash things. Sometimes you laugh, and then feel guilty for it. But the other side of it is this: it’s a reminder of what we felt for that person. If we didn’t love, it wouldn’t hurt.

My eldest brother, Dave, was probably one of the reasons I ended up becoming a doctor. As a young adult, he underwent surgery to replace his aortic valve. I wasn’t old enough yet to really understand the significance, except to say that I knew he had to be on blood-thinners and I worried about him perpetually walking around barefooted. Also, when it was really quiet, you could hear him tick.

But eventually that wasn’t enough, and things got worse. Again I didn’t really understand it; all I knew was that he couldn’t seem to keep up or get enough breath in; his ankles were getting more and more puffy. I remember abandoning a year-12 trial exam to go up to Sydney with him to wait, in one of those timeless, fluorescent-lit hospital-corridor side-rooms, with coarse carpet and hard plastic chairs. You know the ones, if you’ve waited too. He’d finally gotten the call-up. And now we were waiting, waiting; to see if he’d survive surgery or not.

He did. He recovered. He lived. It was a wonderful second chance that would not have been afforded to him, without modern medicine.

Dave died on 5 December 2020. He’d made it to 43, following a heart transplant aged 27. How scared he must have been, I sometimes think. In the year after his death, the emotions I survived were an ocean, at times entirely too vast, too much, with lows that sometimes made me afraid I might drown. So I sought help, and was linked in with some good mental health assistance, for which I’ll always be grateful.

Yet, I struggled to return to work. My concentration was next to non-existent, almost everything I did or heard or saw reminded me of him, or what he’d never be able to do again.

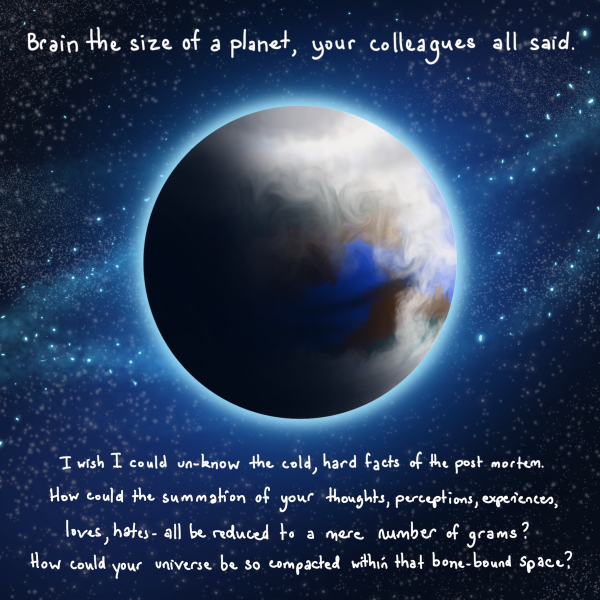

Due to the nature of his passing, questions had to be asked of the coroner and an autopsy report was provided to us. There is something brutal about seeing the gram weight of your dead sibling’s organs, in black and white, on a clinically sterile document, which described nothing of his talents, his humour, what he meant to us. He was a prodigiously intelligent fellow; a computer programmer, musician, son, brother, husband, father, pianist, and so much more.

There is something kind of magical about the human imagination, though, and its capacity to generate art. We are complex, flawed creatures. Once, when puzzling out a difficult circumstance, Dave wrote, “Maybe a song will help me know”.

Personally, I struggle to express myself verbally when I am trying to work through complex emotions. Sometimes when I felt livid, or devastated, or indeed anything that just seemed like too much for my finite brain to handle, instead of tears spilling out of me, it was a song, or a drawing. So I wrote. I drew. I sang. I cried. I cried some more.

By the end of a year I’d strung together 32 pages of musings, drawings, feelings, and put it all together, and had it printed – giving it the title Grief: what an a**hole. Because, frankly, that’s what it felt like sometimes.

But more and more, lately, I’m getting used to sitting with it. I’ll always be sad about it, don’t get me wrong. But it was cathartic to hold a printed book in my hands, knowing that I’d made something (and something relatively beautiful, at that), out of pain.

So. Why am I telling you this? A lot of healthcare workers seem to be struggling, right now. Understandably so. If you’re a person who struggles to express yourself in speech, I implore you: pick up a paintbrush, a pencil, a pen. An instrument. Sing. It doesn’t matter if it’s good or bad, if it holds meaning for you and the people you love, and you get something out of it.

Make something. Anything. And when you do, I’d love to see it. I honestly think it helped me to survive that hellish first year. Maybe it will help you to survive something, too.

Dr Jess Webster is an FRACGP practising in Sydney.

If creativity helps you cope, or you have some work you’d like to see published in TMR, tell penny@medicalrepublic.com.au.