Timely referral and treatment is key to avoiding debilitatingly painful presentations and serious complications.

Herpes zoster (shingles) is becoming increasingly common in Australia. Herpes zoster ophthlamicus (HZO) occurs when latent varicella zoster virus reactivates in the trigeminal ganglion.

HZO occurs in about 10-25% of cases of shingles and is associated with significant longer-term morbidity(1). The elderly and immunocompromised have a significantly higher risk of developing serious sequelae from HZO than the general population.

Varicella zoster virus reactivates when host T-cell-mediated immunity diminishes and is increasingly common in those over 60 years of age.

There is evidence that the incidence of HZO is increasing in all age groups, especially in the 60-plus, with an estimate ranging from 14 to 19.9 per 1000 per year(2, 3). Post-herpetic neuralgia occurs in about 30%, with up to 50% developing ophthalmic complications of HZO(4).

Early recognition of the symptoms, prompt introduction of antivirals and appropriate analgesia can improve patient outcomes. Viral transmission from patients with zoster can occur but is less frequent than from patients with chickenpox(5).

Diagnosis

Symptoms and signs

The prodromal phase of a non-specific influenza-like illness can precede the rash by up to a week and makes an early diagnosis a challenge.

Patients may present with a non-specific red eye, foreign body sensation and initially be thought to have conjunctivitis before the onset of the typical vesicular rash. In rare cases, patients can have atypical presentations without the rash (zoster sine herpete), where a high index of suspicion is required(6).

HZO can affect all aspects of the orbit, the eye and its cranial nerves with a varying time course.

Hutchinson’s sign, defined as a lesion at the tip, side or root of the nose, due to involvement of the nasociliary nerve and ethmoid nerves, is a strong indicator of ocular inflammation (3.3-fold increase), as is corneal denervation (four-fold increase)(5). However, ocular involvement can develop in the absence of Hutchinson’s sign.

Table 1 highlights the common and sight-threatening complications of HZO. HZO can result in a multitude of different complications. Corneal complications such as loss of corneal sensation can result in a corneal melt or perforation and is an ophthalmic emergency. It is estimated that 5-10% of patients with HZO can develop reduced sensation and be at risk of this complication.

| Symptoms/signs and red flags | Time course | |

| Eyelids and conjunctiva Blepharoconjunctivitis Secondary Staphylococcus aureus infection | Cutaneous rash respecting midline Conjunctival oedema/follicular conjunctivitis P Worsening swelling, yellow discharge from vesicles | Day 0 (can precede the rash) |

| Episclera/sclera | Localised or diffuse swelling, pain P Severe pain (scleritis) | 0-14 days |

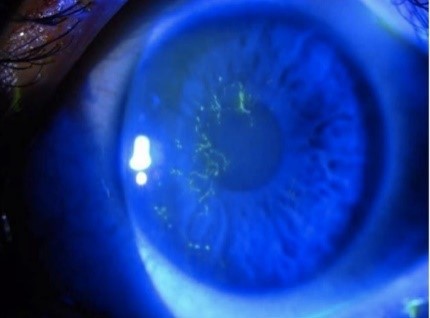

| Cornea Punctate epithelial keratitis Dendritic keratitis Stromal keratitis Neurotrophic keratopathy | Foreign body sensation, sharp pain Small erosions on fluorescein staining with high magnification (very common) P “medusa-like’ epithelial defect with tapered ends (common) P Inflammation with neovascularisation +/- corneal thinning P painless red eye, infiltrate/white deposit on cornea (under-recognised) | 0-10 days < 7 days Onset within first few weeks – ongoing issues |

| Uvea – iris, ciliary body and choroid Uveitis with high intraocular pressure Iris atrophy | P Photosensitivity, dull ache, headache Leukocytes in the anterior chamber, iris transillumination defects | Variable 0-14 days Months after initial episode |

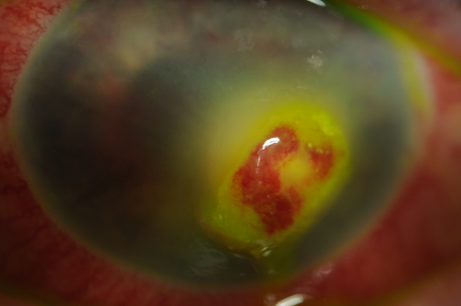

| Retina Acute retinal necrosis Occlusive vasculitis | P floaters, reduced vision, painless Retinal whitening, vasculitis and disc swelling (fundoscopy) | Variable |

| Optic nerve Optic neuritis | Reduced vision P Relative afferent pupillary defect (RAPD) Field changes on automated perimetry | Variable |

| Cranial nerves Oculomotor palsies | Binocular diplopia, Head tilt, eso deviation (eye turned in), exo deviation (eye turned out) | Variable Weeks to most post HZO |

| Meningoencephalitis | P Confusion, neck stiffness, photosensitivity, generalised neurological symptoms |

Laboratory investigations

Detection of varicella zoster virus DNA using polymerase chain reaction from skin vesicles has excellent sensitivity and specificity (> 98%). Varicella zoster virus specific serology tests, especially IgM and IgG, is a useful adjunct to PCR for assessing immune status; however, 50% of reactivations may have a delayed IgM response by days to weeks after symptom onset, limiting the utility.

Management

Acute

Once the diagnosis is suspected or made clinically, antiviral therapy should be initiated (see table 2).

The authors’ preference for outpatient management is valaciclovir 1gm TDS for a course of 7-10 days depending on the patient’s renal function.

In disseminated HZO, features of meningoencephalitis or immunosuppressed patients, hospital admission with intravenous acyclovir 10-15mg/kg every eight hours is recommended(4).

| Valaciclovir | 1g (child older than two years: 20mg/kg up to 1g (orally) 8-hourly for seven days |

| Famciclovir | 500mg orally, eight-hourly for seven days (duration 10 days if immunocompromised) |

| Aciclovir | 800mg (child 20mg/kg up to 800mg) orally, five times a day for seven days |

| Intravenous Aciclovir | 10mg/kg (child 12 years or young: **500mg mg/m2) intravenously, 8-hourly |

Patients with HZO or suspected HZO should be promptly referred to an ophthalmologist for assessment using the slit lamp.

Specialised assessment of the cornea, including sensation, anterior chamber reaction, intraocular pressure and fundoscopy, is important early and as a guide for subsequent monitoring. If there is evidence of varicella retinitis, an intravitreal tap and injection of Foscavir (2.4mg in 0.1mL) is administered(8). This may need to be repeated depending on the response.

A short course of corticosteroids (0.5mg/kg/day) over two weeks may be considered as an adjunct to reduce zoster pain but the risks need to be weighed against the benefits. The acute use of corticosteroids, however, does not decrease the likelihood of post-herpetic neuralgia(9).

In addition to prompt systemic antiviral therapy, early implementation of analgesia for the acute pain associated with HZO is vital and must also target the neuropathic component. In addition to paracetamol and NSAIDs, the addition of amitriptyline 10mg at night or pregabalin 50mg then up-titrated to an effective dose is useful(4).

Opioids are not a preferred option because of a lack of efficacy against neuropathic pain and the risk of adverse effects and dependence(10). Table 3 has other commonly prescribed and trialled agents.

Post-herpetic neuralgia

Post-herpetic neuralgia is challenging to manage and requires a multimodal approach.

Risk factors include intensity of acute pain, ophthalmic involvement as well as older age(11).

Early introduction of anticonvulsant medications such as gabapentin or pregabalin is routinely recommended early during HZO.

Antidepressants such as tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) are also commonly used to manage post-herpetic neuralgia. Both classes of medications can be up-titrated to minimise the risk of adverse effects.

There is evidence that a combination therapy of anticonvulsants and antidepressants with topical agents can be effective(10).

However, topical capsaicin and lidocaine should be avoided near the eyelids and conjunctiva.

| Adverse effects/ considerations | |||

| First line | Anticonvulsants | Gabapentin (300-2400mg/day), pregabalin (50-600mg/day) | Sedation, peripheral oedema, weight gain |

| Antidepressants | Amitriptyline (10-150mg/day) nortriptyline (25-50mg day) | Somnolence, anticholinergic effects and weight gain | |

| Second line | Topicals | Lidocaine 5% (xylocaine) 3-4 times daily (<20g/24 hours) | Avoid periocular use, avoid prolonged frequent use |

| Capsaicin 0.025% 3-4 times daily | Avoid in active shingles, periocular use |

Prevention

There is good evidence from both randomised controlled trials and population-based studies that herpes zoster vaccination reduces the incidence of herpes zoster and post-herpetic neuralgia(1, 12).

The greatest evidence is for the live attenuated Oka/Merck varicella zoster virus vaccine (Zostavax) in immunocompetent individuals over 60 years(12).

Recurrence of herpes zoster is low in the first year after reactivation; however, the chances can increase to 5.3% over 20 years. The current Australian guidelines recommend waiting at least one year post-HZO or herpes zoster before receiving the zoster vaccine(2, 8).

Currently in Australia, Zostavax is available free on the National Immunisation Program for immunocompetent people aged 70-79 years.

However, the live attenuated vaccine is contraindicated in immunocompromised individuals. Shingrix is a recombinant antigen glycoprotein E vaccine that has been recently approved for patients over 50 years and can be safely used in those who are immunocompromised(13).

It is a double-dose vaccine six months apart and has demonstrated efficacy in patients with autologous stem cell transplant, renal transplant and those undergoing chemotherapy(14). Unfortunately, it is not listed on the PBS at this stage, so patients will be expected to pay between $450 and $550 for the two-dose course. It is hoped that this more efficacious vaccine will be listed in the future.

However, given its new addition by the TGA, it is worthwhile considering vaccination in patients over 50 to reduce the risk of HZO and the possible sequalae of post-herpetic neuralgia.

Conclusion

HZO and subsequent post-herpetic neuralgia is increasing in incidence in Australia.

This is probably due to the combination of an ageing population and the increasing use of immunosuppressive medications. As a result, primary care physicians should be aware of the potential complications and current advice regarding management of HZO and post-herpetic neuralgia, as well as the currently available vaccinations.

William Yates is a senior ophthalmology registrar at Sydney Eye Hospital.

Peter McCluskey is a professor and chair of ophthalmology and director of Save Sight Institute at the University of Sydney.

References

1. Litt J, Booy R, Bourke D, Dwyer DE, Leeb A, McCloud P, et al. Early impact of the Australian national shingles vaccination program with the herpes zoster live attenuated vaccine. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2020;16(12):3081-9.

2. Lee E, Chun JY, Song KH, Choe PG, Bang JH, Kim ES, et al. Optimal Timing of Zoster Vaccination After Shingles: A Prospective Study of the Immunogenicity and Safety of Live Zoster Vaccine. Infect Chemother. 2018;50(4):311-8.

3. MacIntyre R, Stein A, Harrison C, Britt H, Mahimbo A, Cunningham A. Increasing trends of herpes zoster in Australia. PLoS One. 2015;10(4):e0125025.

4. Kedar S, Jayagopal LN, Berger JR. Neurological and Ophthalmological Manifestations of Varicella Zoster Virus. J Neuroophthalmol. 2019;39(2):220-31.

5. Liesegang TJ. Herpes zoster ophthalmicus natural history, risk factors, clinical presentation, and morbidity. Ophthalmology. 2008;115(2 Suppl):S3-12.

6. Kennedy PG. Zoster sine herpete: it would be rash to ignore it. Neurology. 2011;76(5):416-7.

7. Shaikh S, Ta CN. Evaluation and management of herpes zoster ophthalmicus. Am Fam Physician. 2002;66(9):1723-30.

8. ATAGI. Zoster (herpes zoster) Canberra Australian Government 2020 [Available from: https://immunisationhandbook.health.gov.au/vaccine-preventable-diseases/zoster-herpes-zoster.

9. Han Y, Zhang J, Chen N, He L, Zhou M, Zhu C. Corticosteroids for preventing postherpetic neuralgia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013(3):CD005582.

10. Shrestha M, Chen A. Modalities in managing postherpetic neuralgia. Korean J Pain. 2018;31(4):235-43.

11. Werner RN, Nikkels AF, Marinovic B, Schafer M, Czarnecka-Operacz M, Agius AM, et al. European consensus-based (S2k) Guideline on the Management of Herpes Zoster – guided by the European Dermatology Forum (EDF) in cooperation with the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology (EADV), Part 1: Diagnosis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2017;31(1):9-19.

12. Oxman MN, Levin MJ, Johnson GR, Schmader KE, Straus SE, Gelb LD, et al. A vaccine to prevent herpes zoster and postherpetic neuralgia in older adults. N Engl J Med. 2005;352(22):2271-84.

13. (ARTG) ARoTG. Zostavax Listing 130229. 2021.

14. Boutry C, Hastie A, Diez-Domingo J, Tinoco JC, Yu CJ, Andrews C, et al. The Adjuvanted Recombinant Zoster Vaccine Confers Long-term Protection Against Herpes Zoster: Interim Results of an Extension Study of the Pivotal Phase III Clinical Trials (ZOE-50 and ZOE-70). Clin Infect Dis. 2021.