Diagnoses are often delayed in this common condition, leading to potentially life-threatening outcomes.

Neck masses are a common presenting complaint in general practice and the differential diagnosis is broad, including both benign and malignant aetiologies (Picture 1).

The diagnosis will typically fall into three broad categories: congenital, inflammatory and neoplastic.1

The importance of an accurate diagnosis lies in excluding an underlying malignancy. In an adult, a persistent, asymptomatic neck mass should be considered malignant until proven otherwise.2

While cancers of all sub-sites in the head and neck account for only around 4% of cancer diagnoses each year in Australia,3 the prevalence of oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma (OPSCC) – that is, cancers of the palatine and lingual tonsils – have increased exponentially in recent years driven by human papillomavirus (HPV) as the underlying causative factor.4

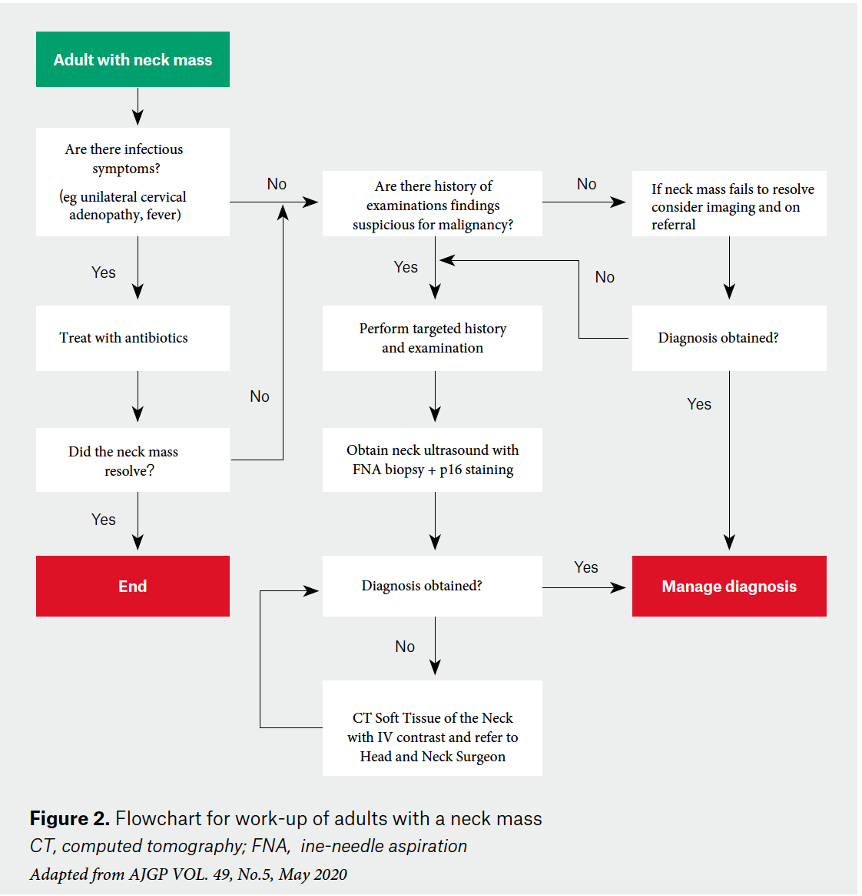

Unfortunately, delays in diagnosis remain common and this can be associated with a significant increase in the morbidity of treatment and, ultimately, the patient’s chance of disease-free survival.5 Early referral to an ear, nose and throat surgeon/head and neck cancer surgeon specialising in treatment of head and neck cancers is vital. The aim of this article is to provide a framework for further investigation and management (Figure 2).

Human papillomavirus (HPV)

The incidence of HPV-related oropharyngeal carcinoma has more than tripled from 19% to 66% between 1987 and 2006.6

The importance of this lies in the fact that the patients affected by this disease are not the typical patients that come to mind when we think about head and neck carcinoma, that picture being of an older patient with a history of significant smoking and alcohol use.

These patients are much younger, sometimes as young as in their 30s, and most of them will be non-smokers. These cancers will most often present with an otherwise asymptomatic neck mass and the nodes will commonly be cystic in nature. Due to the fact that it can affect younger patients, a common misdiagnosis is that of a branchial cleft cyst. This tendency towards misdiagnosis can unfortunately lead to treatment delays.

History and examination

The history and examination can be helpful in guiding a practitioner towards a diagnosis; however, it must be remembered that some patients with an underlying malignancy may present simply with a neck node in isolation, with no other localising symptoms.7

Regardless, the history will often be able to differentiate between an acute or subacute event by identifying infectious or systemic symptoms.

From a malignancy perspective, it is important to ask certain key questions regarding red flag symptoms that can help elucidate if a malignancy diagnosis is likely. These include, but are not limited to:

- Pain or difficulty swallowing (odynophagia or dysphagia)

- Unilateral otalgia with a normal appearing tympanic membrane

- Change in voice

- Epistaxis, unilateral nasal obstruction or recurrent middle ear infections

- Episodes of haemoptysis

- Unexplained weight loss

- Difficulty completely opening the mouth (trismus)

In the broader context of non-HPV-related head and neck malignancies, it is also important to consider if the patient has a previous history of head and neck childhood irradiation, if there is a cutaneous lesions affecting the head and neck region or if there is any family predisposition to head and neck malignancy; that is, nasopharyngeal carcinoma in patients of south-east Asian descent.

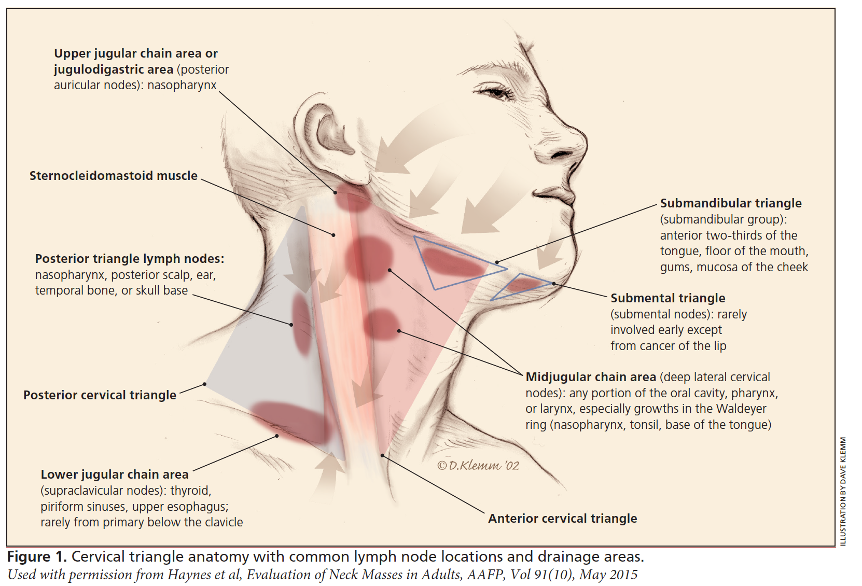

Assessing the location of the neck mass is essential as it will help point the examiner towards the underlying affected anatomical subsite.

The neck is typically divided into six levels of nodal distribution.

- Level I: the submental and submandibular triangles

- Level II, III IV: the upper, middle and lower internal jugular chain

- Level IV: the posterior triangle

- Level IV: the anterior compartment.

Figure 3 helps to delineate which structures will typically affect which particular nodal basin. For oropharyngeal carcinomas, level II and II are the most commonly affected nodal levels.

Radiological investigation

Ultrasonography

Ultrasound is the least invasive of the imaging techniques and provides a real-time assessment of a neck mass and its relation to adjoining structures.

Ultrasound is an excellent initial imaging modality in the first instance, particularly as it can be paired with histopathological investigation in the form of fine needle aspiration (FNA) or core biopsies.

There are several disadvantages to ultrasound, however, including dependence on operator expertise and limited permanent images for use in consultant evaluation or the operative setting.

Computed tomography (CT) soft tissue of the neck

Contrast enhanced CT of the neck yields excellent anatomic detail and should be used to add to the clinical picture that has been provided by an ultrasound. It can assist in the localisation of the primary neoplasm, assess for further lymphadenopathy and aid in the staging process. Contrast should also be administered for enhanced soft-tissue differentiation unless there is an absolute contraindication such as iodine allergy.

MRI of the neck with contrast

Although MRI does provide better soft-tissue delineation, it is not required as part of the initial work-up for a neck mass. An MRI would typically be performed to answer a specific question that would help guide cancer management after the initial diagnosis had already been established.

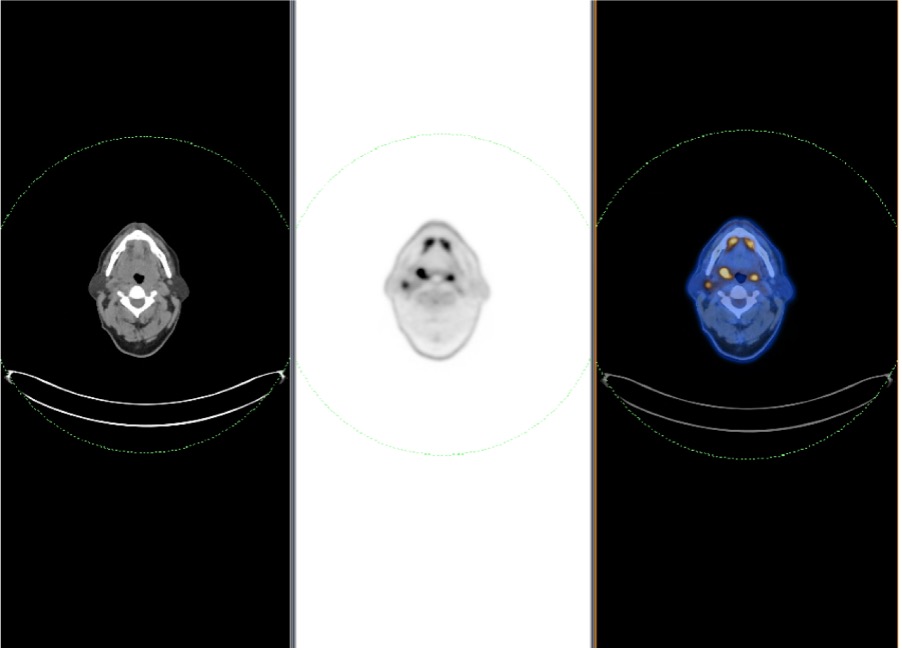

Positron emission tomography

PET/CT fusion scans (Figure 4) are very useful in the setting of malignancy, aiding in the identification of primary disease or detection of distant metastatic disease. PET/CT is primarily helpful in the later evaluation of malignancies and plays little role in the initial evaluation of the neck mass.

The oncological surgeon or physician would typically order a PET scan once a cancer diagnosis has been established in order to aid with overall staging of the disease.

Histopathological investigation

An ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration biopsy is the first-line diagnostic test for patients presenting with a neck mass.

It is important to also order p16 staining, which is a surrogate maker for HPV, as part of the biopsy request. This will guide diagnosis because, if a SCC shows p16 staining positivity, it probably means that the primary site is the oropharynx.

p16 immunohistochemistry has become the recommended standalone prognostic test for patients with OPSCC as it is more cost-effective and less technically cumbersome than HPV-specific testing (i.e., in situ hybridisation and reverse-transcriptase PCR), is widely available, has high interobserver agreement in its assessment and has been consistently shown to have independent prognostic significance.8

Treatment

All patients who have been diagnosed with a head and neck cancer should be reviewed at a dedicated head and neck malignancy multidisciplinary team meeting (MDT).

Apart from influencing treatment decisions, MDTs have also been shown to improve cancer staging and subsequently patient outcomes. Consequences of non-MDT management include the possibility of less-accurate staging, lack of allied health input and loss to follow-up, due to the lack of coordinated care that is available in MDT settings.9

Patients with HPV-related OPSCC have a 75% five-year survival rate as opposed to those with HPV-negative disease where the five-year survival is in the realms of 50%.10

There are two excellent treatment options available for these patients: radiation +/- chemotherapy or surgery with adjuvant therapy guided by the surgical pathology. The choice of treatment will depend on patient factors, tumour factors and institution factors.

The primary aim of any cancer treatment is to provide long-term oncological control. With head and neck cancers, the secondary, but almost equally important, aim is long-term swallowing and speech outcomes. Additionally, given the fact that this affects patients in a younger demographic, the risks of radiation-induced second primary cancers is a real concern.11

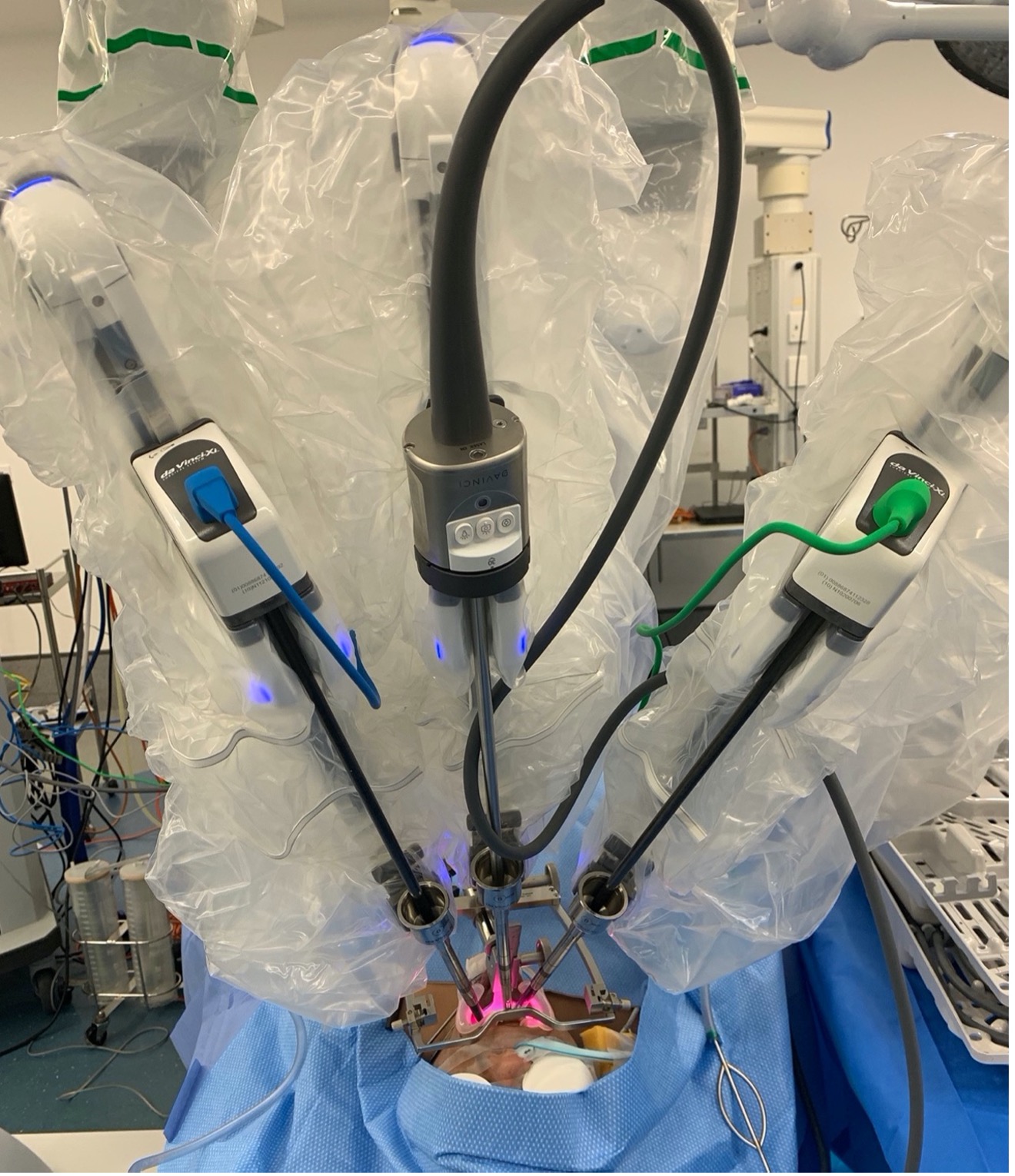

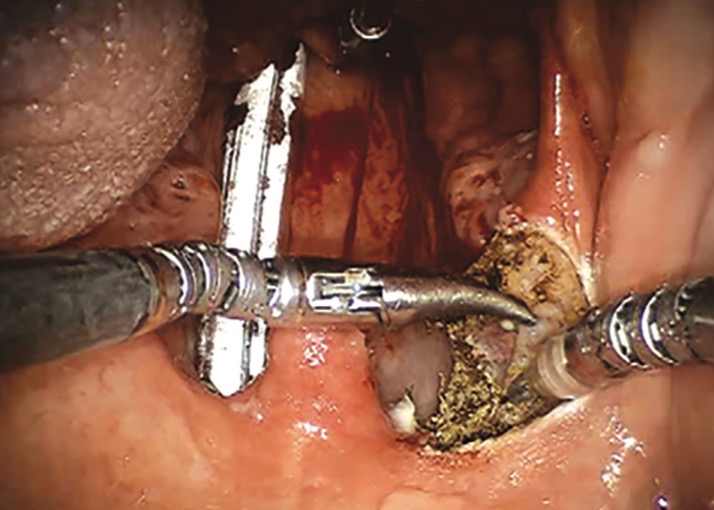

Trans-oral robotic surgery (TORS)

TORS (Figure 5a/b) has revolutionised the way surgery can be used to treat head and neck carcinoma, particularly oropharyngeal carcinomas. It allows areas of the upper aero-digestive tract to be reached in a minimally invasive way and can decrease the long-term morbidity of treatment while maintaining the oncological outcome.

Conclusion

In the adult setting, if a neck mass has been present for more than six weeks, further investigation should be undertaken. This will probably include an ultrasound-guided FNA biopsy, contrast-enhanced CT scan and subsequent referral to an ENT specialist to facilitate ongoing treatment.

- Deschler DG, Zenga J et al. Evaluation of a neck mass in adults. Up to Date [Internet] 2021. Available from https://www.uptodate.com.acs.hcn.com.au/contents/evaluation-of-a-neck-mass-in-adults?search=Investigation%20of%20a%20neck%20mass&source=search_result&selectedTitle=1~150&usage_type=default&display_rank=1

- Haynes J et al. Evaluation of neck masses in adults. AAFP 2015; 9(10):698-706

- Head and Neck cancer in Australia statistics [Internet] https://www.canceraustralia.gov.au/cancer-types/head-and-neck-cancer/statistics

- Tan E, Jaya J. An approach to neck masses in adults. AJGP 2020;49(5):

- Seoane J, Takkouche B, Varela-Centelles P, Tomás I, Seoane-Romero JM. Impact of delay in diagnosis on survival to head and neck carcinomas: A systematic review with meta-analysis. Clin Otolaryngol 2012;37(2):99–106

- Hong A, Lee CS, Jones D, et al. Rising prevalence of human papillomavirus-related oropharyngeal cancer in Australia over the last 2 decades. Head Neck 2016;38(5):743–50

- Floros P et al. Altered presentation or oropharyngeal carcinoma, a 6-year review. Aust NZ J Surgery. 2021; 91(6):1240-1245

- Shelton J et al. p16 immunohistochemistry in oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma: a comparison of antibody clones using patient outcomes and high-risk human papillomavirus RNA status. Modern Pathology 2017;30: 1194-1203

- Friedland PL et al. Impact of multidisciplinary team management in head and neck cancer patients. BJC 2011; 104(8):1246-1248

- Perri et al. Management of HPV-related squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck; pitfalls and caveat. Cancers 2020;12(4): 975

- Bradley PJ. Radiation-induced tumors of the head and neck. Current opinions in Otolaryngology & head and neck surgery. April 2002;10(2):97-103