It’s a serious problem, but it may be on a smaller scale than some are claiming. An epidemiologist looks at the data.

Of the many ongoing issues in the pandemic, one of the most difficult is long covid.

Despite being a serious condition plaguing many people who recover from their initial covid infections, particularly for those who suffer debilitating, long-lasting symptoms, long covid is nevertheless often invisible, hard to diagnose, and even harder to treat. There are endless terrifying stories online about previously healthy people who were struck down, sometimes after quite mild initial covid infections, with persistent disabling symptoms.

In other words, long covid is a serious problem, and something that we as a society need to grapple with as a consequence of the pandemic.

Recently, there has been a very tumultuous debate about a key point — how many people do we expect to get long covid after their initial infections? Headlines abound with terrifying statistics implying that nearly everyone will eventually get this condition, that more than 1/3 of covid sufferers are still suffering, and that we are all essentially doomed to be sick.

However, the reality is far more complex. A lot of this depends on definitions, and when you look at the data the proportion of people who have long covid is a very complicated topic, and may well be quite a lot lower than you’ve heard. Of course, a small proportion of a very large number is still a lot of people suffering, but the actual percentage may be quite a lot lower than scariest headlines suggest.

Let’s look at the evidence.

Definitions

Definitions matter in epidemiology. An expansive definition of a disease will always include more people, but may also reduce the usefulness of the term. A narrow one may be more useful clinically, but will exclude people who may be suffering a milder version of the same illness.

In a new and poorly understood disease, choosing the right definition goes from important to critical. We could use the World Health Organization’s clinical case definition, which was generated after a lengthy consultative process with patients, caregivers, and healthcare experts, which states:

Post covid-19 condition occurs in individuals with a history of probable or confirmed SARS CoV-2 infection, usually 3 months from the onset of covid-19 with symptoms and that last for at least 2 months and cannot be explained by an alternative diagnosis. Common symptoms include fatigue, shortness of breath, cognitive dysfunction but also others and generally have an impact on everyday functioning. Symptoms may be new onset following initial recovery from an acute covid-19 episode or persist from the initial illness. Symptoms may also fluctuate or relapse over time.

This is pretty expansive, but if we look at the scariest, very high estimates, almost all of them use definitions even broader than this one. For example, a recent CDC study headlined with “Nearly One in Five American Adults Who Have Had Covid Still Have “Long Covid””. If you look at the technical notes, this includes people who said they’d had covid and any new symptoms lasting three months or more.

It’s easy to see why this might produce such a high figure. If you ask people whether, at any time since they had covid (which may have been well over a year ago) they’ve had any of a wide range of symptoms, it’s not entirely surprising that quite a few people will answer yes. Fatigue, as an example, is one of the most commonly reported symptoms of long covid, but is also quite common in people who were never exposed to covid.

Another concern is the population being studied. This systematic review and meta-analysis estimates that the global prevalence of any long covid is 44% after recovering from the initial infection, but it includes mostly studies of either hospitalised people or very specific populations like those over 65. If we look at estimates based on representative samples of the entire population, the prevalence falls dramatically, with one study finding just 3.4% of people had symptoms at 4+ months.

You can also delineate this issue by thinking about severity of disease. Using the WHO and CDC definitions, long covid is any symptom of any severity — this tends to include everything from a very mild on/off headache lasting a few months to serious disabling disease. However, if you were to narrow that down to symptoms that cause severe impacts on daily life — which is potentially more clinically useful — that proportion necessarily drops.

You can see this in the data — a recent Office for National Statistics report from the UK identified that 3% of the entire population was experiencing some form of long-lasting covid symptom. In this population, about 72% of people reported that these long-lasting symptoms adversely impacted their life, and 20% reported that the symptoms limited their daily activity by a lot. In other words, the headline figure was that 2 million people had long covid, but only one-fifth of those people had serious, debilitating disease.

Now, it’s important to note that one-fifth of 3% of the entire population is still a very large number in absolute terms — in the UK, that’s >400k people. Regardless of which measure you pick, long covid is still a big problem that is impacting the world.

But from here, it gets even more complex. How do we know that all of these symptoms are directly caused by covid?

Control groups

This brings us to a contentious point in the long covid debate: should we compare people to a control group who didn’t have covid to see if the symptoms that people are reporting are likely caused by the virus itself? The idea is that we can’t necessarily say that covid is causing all of the long covid symptoms that we see, because there is some baseline level that people would experience regardless.

Take this recent study — of those people who were not hospitalised with covid in their dataset, the authors found that 5.4% of people had long-term symptoms months after their initial covid diagnosis. However, in a group of control patients who were not diagnosed with covid, there was a rate of persistent symptoms of 4.4%. While there’s some discussion about the limitations of this paper — you can check my Twitter thread and the ongoing debate if you’re interested — the point is that some proportion of those people who reported symptoms might’ve reported them even if they’d never had covid.

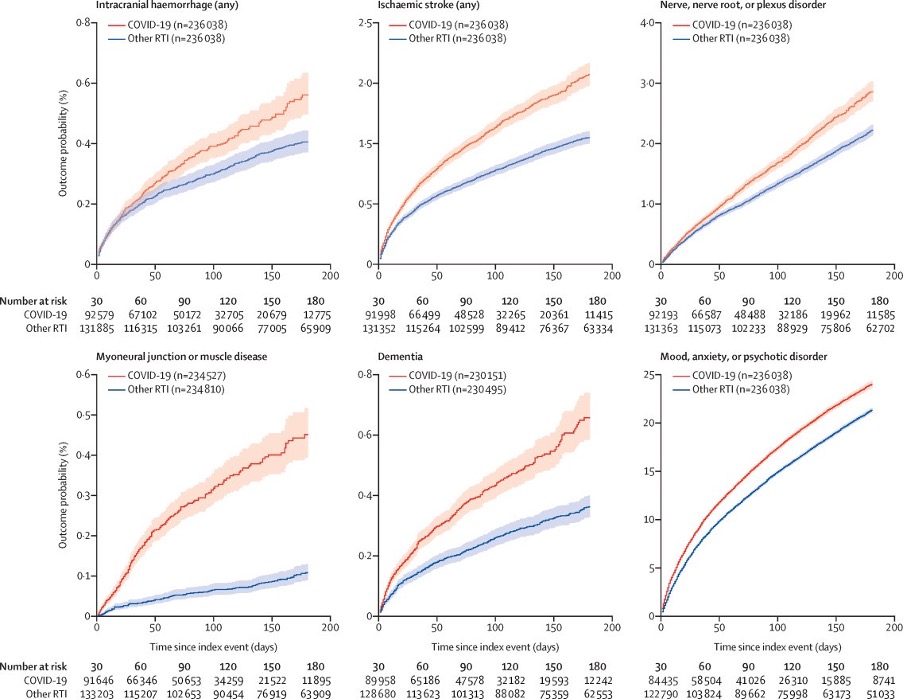

You can apply this sort of analysis to other estimates of long covid as well. One of the most commonly cited papers in the long covid literature estimated that 34% of people who got covid would have persistent neurological or psychological issues, which was the number picked up in news headlines and scientific reviews alike. However, if you compare this to the control group in the study, it’s more like 5-8% more than the expected baseline experiencing such symptoms, which could indicate that only 5% of the symptoms seen were caused by covid itself.

Of course, this gets even more complicated once we start considering what control groups represent. If we’re comparing to a control group of people who’ve recovered from other viral illnesses like influenza, does that simply mean that lots of viruses cause long-term symptoms? If there is a higher rate of chronic nerve disorders in people who’ve had a fracture than those who had covid it probably doesn’t mean that covid is protective against nerve disorders but might it mean that these are not related to long covid? It’s very hard to say.

These issues can, to an extent, be ameliorated by using a general population control — i.e. comparing to everyone in society — but that runs into its own issues. A lot of people who have never been diagnosed with covid have previously had an infection, after all, something we know from studies looking at people’s antibodies.

All of that aside, this does bring us back to the central point about definitions. Technically, if we adhere to the WHO definition cited above, and exclude people whose symptoms might be explained by causes other than covid using a control group, the rate of any long covid after an infection drops dramatically from 20-30% down to around 1-10% instead, depending on study and population.

And this is before we even start to discuss the difficulties in residual confounding, confounding by indication, and other epidemiological biases in studies that attempt to determine the causal relationship between covid infection and long covid symptoms. It’s very hard to know exactly what proportion of people who report persistent symptoms after a covid infection have symptoms that were caused by the infection itself. This does not mean that the symptoms aren’t “real” — people are obviously suffering — but it does mean that we may not be able to blame covid infections for all of the persistent illness that we see.

Falling proportion

There’s another very interesting thing to note about long covid, which is that in study after study it is very closely tied to the severity of disease. What I mean by this is that the rate of people experiencing long-lasting symptoms after recovering from covid is much lower in those who have mild initial infections, and goes up to extremely high levels in those who have very severe disease.

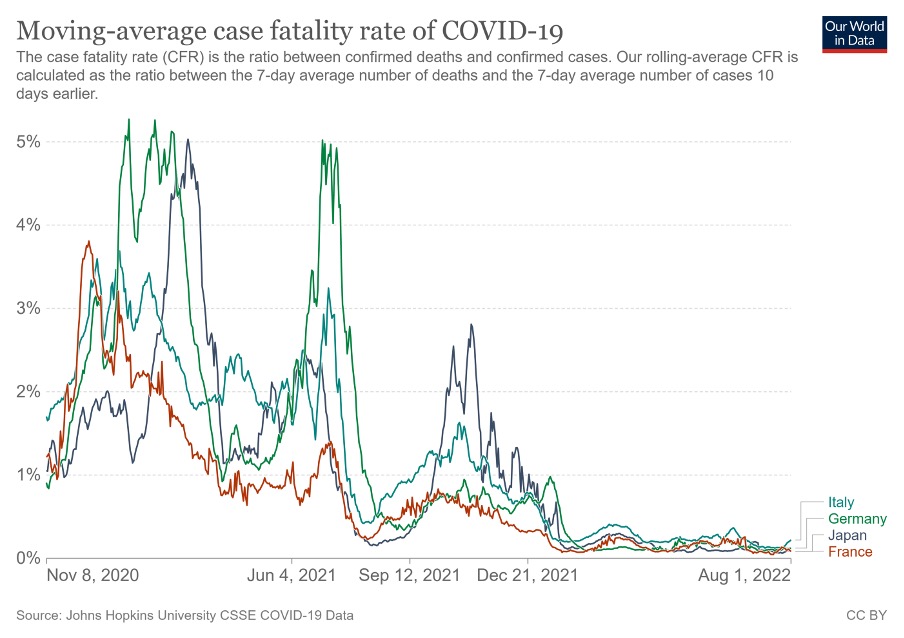

The reason that this is interesting is because we know, from a great deal of research, that the proportion of people who are experiencing severe covid infections has fallen dramatically. Estimates vary, but the combination of vaccination and immunity from past infections has massively reduced the rate of people getting really sick from covid.

Taken together — long covid is related to disease severity, and disease severity is falling over time — these facts strongly imply that fewer people will get long covid from infections now than in 2020, and in the future this will probably fall further.

Indeed, there’s even some evidence this is the case — we know that vaccination reduces the rate of long covid, potentially by a very large proportion, and we’d expect previous infection to offer a similar protection. We can even see an indication of this in population statistics — despite massive increases in the number of people infected in 2022, the proportion of those with long-lasting symptoms has barely shifted since January in the UK and may be falling as time goes on.

Altogether, this means that your risk of long covid today is probably much lower than your risk if you were infected in 2020, and the risk of an infection in 2024 is likely to be lower still.

Bottom line

It’s important to note that nothing in this piece — nor anywhere in the evidence itself — shows that people are not experiencing symptoms. No one is lying about being ill, and regardless of which definition we use the fact remains that people are suffering and that is a very big issue.

However, it is important to be clear about what using different definitions for long covid means in practical terms. If we decide that long covid should be described using the CDC definition, then a lot of people who’ve had covid would meet the criteria. That being said, many of those people would have very mild concerns, that resolved fairly quickly, which may not have been caused by covid.

If we instead use something like the WHO’s definition, and include a control group into our assessment, we end up with a much smaller proportion of people having long covid. That’s still a huge issue, but perhaps slightly more manageable than the estimate that everyone will eventually experience permanent harm due to covid.

On top of that, we’ve got the debate about long-lasting impacts to various organ systems, like the paper that found an increased risk for heart problems post-covid or another that found similar issues in the brain structures that relate to the sense of smell. These mostly show quite similar results to the symptom studies in terms of prevalence rates, but they do indicate some proportion of people who have underlying damage who may not report symptoms in a survey*.

Since we’re more than 2,000 words into the piece, it’s tempting to sum this all up with something short and sweet. Maybe “long covid is a huge problem, but not quite as big as headlines suggest”, which is entirely true although perhaps a bit glib.

But I’m not going to do that. The key message here is that this entire question is complicated, and anyone who says any different is probably wrong. In my opinion, the studies with control groups give us a good idea of the proportion of people who experience symptoms long-term that are directly related to their covid infection — in this case, it’s probably somewhere around 1–10% of people who get infected, potentially less. That proportion is also likely to be falling substantially over time, although the exact rate of decline is hard to estimate.

That being said, this still leaves us with a huge group of people who are experiencing symptoms even if they are not related to covid, and no good answer about what’s causing those issues — remember, more than 400,00 individuals in the UK. That’s not a small number! The issue may not be as disastrous as some headlines suggest, but it still has chilling consequences for our society.

It’s hard to know exactly how many people will get long covid after a coronavirus infection. What we do know is that it is a big problem regardless.

*Of course, this itself is complex because depending on how you ask your questions in a survey you can find wildly different numbers of people say “yes” to any specific question. None of this is easy, all of it is complicated.

Thanks to James Heathers and Kate Green Tripp.

Gideon Meyerowitz-Katz is an epidemiologist and PhD candidate who tweets as The Health Nerd @GidMK.

This piece was originally published at Medium.