Home visits are on the rebound, but not everyone is welcoming the trend

Home visits are on the rebound as the growth of medical deputising services surges. But not everyone is welcoming the trend

Dr Nick Demediuk was once a radio doctor riding around in a pint-sized Datsun with a beeper, taking job details over a public phone. Later, he made late-night and morning visits to his regular patients, because that’s what most GPs did back then.

He doesn’t miss the Radio Locum era, particularly the threats to his person. “We didn’t have computer records about drug-seekers; you’d go at night to some scary places with people putting it on you for drugs,” Dr Demediuk says. “It was a much more dangerous occupation.”

Over the years, he and many other GPs increasingly shunned after-hours work because it was simply onerous: exhausting, badly paid and alien to any hope of work-life balance.

“Old buggers like me, the silver tsunami of doctors, got sick of doing home visits. Driving around doing home visits all morning as we used to do just isn’t efficient. One thing locum services do is they make it work as a business.”

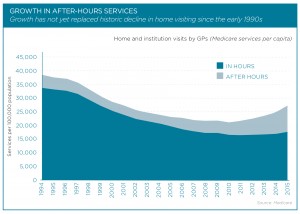

Now home visits are on the rebound after a long decline largely due to a surge in corporate-style medical deputising services. Dr Demediuk is part of the revival as Victorian clinical director for National Home Doctor Service (NHDS), providing mentoring and back-up for doctors in the field.

The Melbourne GP says he has peace of mind knowing his own patients will be looked after at night and a note will appear on his computer desktop with details of any care provided. “That’s great, I can see what’s happened to the patient, I’ve got continuity of care.”

Yet many doctors are alarmed by what they see as aggressive profit-driven tactics and suspected shifty billing practices that have apparently washed up on the same tide of change.

There is no argument that as GPs vacated the after-hours turf, deputising companies moved in and prospered. This was in fact considered a policy success, one of the few linked with the commonwealth-funded Medicare Locals created in 2011.

Given control of after-hours financial incentives, Medicare Locals had more than $120 million a year to spend on encouraging after-hours providers and promoting public awareness of after-hours care. It was their job, part of the effort to reduce the load on hospital emergency departments.

As a result, businesses operating under the government’s Approved Medical Deputising Service (AMDS) program proliferated from 16 in 2006 to 83 in 2014. Today the number stands at 120.

Some 90% of general practices now use deputising services to some extent. The majority simply pocket a dollar per patient in practice incentive payments for turning over their phones to an AMDS provider at the end of the day.

NHDS, the private equity-backed outfit that has grown, largely through acquisitions, to become king of the hill in three short years, is nominated by 2000 practices as their preferred after-hours service. It holds half the market and has locums in all population centres of 100,000 or more except Cairns, where it is launching soon.

But it’s mighty hard to establish who commands oversight of this booming industry and what happens on the fringes.

Only 20 of the 120 AMDS companies belong to the National Association of Medical Deputising Services (NAMDS), the peak industry body. The 20 members include six companies belonging to NHDS and four affiliated with the 45-year-old Australian Medical Locum Service.

That leaves 100 accredited providers outside the club, which demands members sign a statutory declaration pledging they will not break the law. GP accreditation for deputisers is obtained through Australian General Practice Accreditation Ltd (AGPAL) or Quality Practice Accreditation Ltd (QPA).

RACGP President Dr Frank Jones says many new providers outside the NAMDS umbrella are “not recognised as general practice in the general practice definition”.

Currently, the college does not have a definition of what a deputising service does or should do, but it is pushing for better governance and more transparency. It wants a requirement that vocationally registered GPs are at the centre of after-hours care, and is seeking consultations with government to work on improved standards and accreditation for primary care in the 24/7 economy.

“The days of GPs working all night and working the next day are gone – and they were never very healthy days, anyway, for doctor or patients,” Dr Jones says.

“Because of patients’ expectations and Gen-Y attitudes, after-hours has become a very difficult area. I think there is unmet need. But can we afford for consumerism to drive this?” he asks.

“For example, if you have forgotten your pill script, is it appropriate to call a doctor at 11pm, to get a new prescription, subsidised by Medicare? We can debate that. Patients need to think about that.”

Canberra GP Dr Thinus van Rensburg says he is more than happy to have his patients seen by an after-hours deputiser. He has heard no complaints about clinical care, and it’s less work for him. But, after reviewing patients’ records, he suspects urgent MBS item numbers are being used for non-urgent conditions.

“Of the 59 cases I looked at, I could confirm the billing of 20% of them, and every one was a 597, the item number for urgent, rather than non-urgent, home-visit calls between 6 and 11pm. Of those, one was for a patient who is known to have epilepsy. Another was a lady who thought she had high blood pressure. All the rest were kids with colds and flu.”

For non-urgent cases, the service should bill the less expensive non-urgent item number, he says.

“At the end of the line, Medicare is the government-funded insurer, and if you don’t follow the insurer’s rules, it’s illegal. They argue about the semantics, they say the patient said it was urgent. But it’s not up to the patient, it’s up to the doctor to decide.

“What they need to do is show a correlation between the item numbers used and the actual clinical diagnosis.”

Responding to a doctor’s query, the Department of Human Services has issued a clarification saying the application of “urgent” Medicare items is a matter of judgment.

“The requirement of the item descriptor is met if patients’ concerns about their condition are of such alarm to them that most medical practitioners would respond to them urgently,” it said.

Dr van Rensburg fears Canberra’s GP-owned and operated after-hours service, CALMS, where he works on the back-up roster and which charges most patients a substantial co-payment for mostly clinic-based, or non-visiting, care, might suffer from rivalry with bulk-billing market leader NHDS.

So far, CALMS’ medical director, Dr Ian Brown, says there has been little change in patient numbers. “The drop is in in-hours GP care,” Dr Brown says.

This is an unfortunate outcome, he says, since it reduces the opportunity for patients to build rapport with their GP and have simpler things explained.

“A deputiser really should have a relationship with the daytime practice.”

The same story seems to be playing out at the long-established GP Access After Hours (GPAAH) service that operates a roster of 250 GPs working out of five hospital-located clinics around Newcastle, NSW.

GPAAH has not seen a fall in patients coinciding with direct marketing by a home-visit service, but neither have emergency departments in the Lower Hunter region witnessed a drop in low-acuity patients, GPAAH clinical director Dr Lee Fong says.

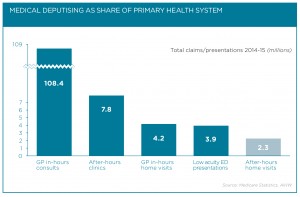

“This suggests the additional $3 million in annual urgent after-hours home visit MBS revenue being billed in our region is coming from patients who are being diverted from daytime general practice,” Dr Fong says.

If so, he says, rather than saving the taxpayer money by converting an ED visit into an after-hours MBS item, a $37.05 day-time GP MBS item is being converted to an urgent after-hours $129.80 MBS item.

Medicare figures show annual billings MBS item 597 – urgent after-hours visits – rose to $21.6 million in 2015, a 3.2-fold jump from $6.1 million in 2011. Across all item numbers, after-hours visits come to $230 million a year.

Dr Fong likens direct marketing of home visits to offering consumers a free pizza delivery. Even the pizza is free! Who would say no? But if people realised every time they ordered the service $130 was disappearing from the health budget, they might think twice about it, he says.

The Department of Health, which runs the Approved Medical Deputising Service program, says all deputisers must abide by the NAMDS definition of a deputising service whether they are members of that organisation or not.

The definition is: “An AMDS is an organisation which directly arranges for medical practitioners to provide after-hours medical services to patients of Practice Principals during the absence of, and at the request of, the Practice Principals.”

You and I might struggle to reconcile these words with the glaring fact that marketing campaigns are underway, in letterboxes, on TV, pitched directly at consumers with no recourse to practice principals whatsoever.

Some providers argue that the NAMDS definition is unclear about whether both conditions – the absence of principals and acting at their request – need to be met concurrently, or if one is enough.

Privately, however, industry sources deplore advertising inviting hotel guests, for example, to take advantage of “free”, convenient medical services.

That’s a no-no under the NAMDS charter, paragraph 11: “As Medical Deputising Services do not offer comprehensive GP care, direct advertising to encourage patients to use Medical Deputising Services for ‘routine’ or convenience purposes, thereby compromising their access to the full range of GP services, is prohibited.”

The concerns about maverick behaviour bring to mind the 2014 review of the after-hours sector by Professor Claire Jackson, who urged government to conduct an urgent examination of the drivers behind a rapid escalation in deputising services’ utilisation of MBS item numbers, particularly for aged-care patients.

Back then, Professor Jackson said the increase raised “questions around the appropriateness of a purely fee-for-service funding model”, and reported anecdotal evidence that some services were “overzealous in turning calls into home visits”. No such inquiry has ensued, however.

There are also claims that some less-scrupulous businesses take advantage of AMDS status by hiring overseas-trained doctors to staff late-night clinics in urban areas but fail to meet their obligations to provide 24-hour coverage and home visits.

Since the AMDS program’s inception in 1999, deputisers have been allowed to hire such doctors, who would normally be restricted mostly to rural regions under the 10-year moratorium, as the after-hours space is regarded as an “area of need”.

Among other complaints, some GPs say that patients who’ve used a home visit service have been urged to call the same service again if their condition persisted, rather than suggest a trip to their regular doctor, as is required.

Dr Cameron Loy, a GP for 10 years but a general practice owner, in Geelong, Victoria, for only one, says this scenario is confronting. He looks after palliative care patients and sick children out of hours but says a business model for comprehensive after-hours care doesn’t exist. “It just ends up as doing good deeds,” he says. “I am certainly looking at ways we could do it better.”

Dr Loy is one of many GPs who is suspicious about the jump in after-hours urgent items claimed by corporate players.

“There’s a perception that there are two different sets of rules running. Were a community general practice to start doing this, there’s a very strong perception that they’d come down on us pretty quick,” he says.

“I can guarantee, if I suddenly had a couple of hundred urgent attendances appear out of this practice, we’d be audited pretty fast.”

Ben Keneally, CEO of NHDS and the current president of NAMDS, says his company’s recent leap into TV and radio advertising is about raising low public awareness, and its services are keeping patients out of hospital.

“The growth in services reflects real unmet need,” he says, noting that home visits have not regained the levels seen in the 1990s. The majority of patients seen are the vulnerable elderly or very young children. In other age groups, attendance at after-hours clinics far outstrips home visits.

He also points to a massive difference in low-acuity ED presentations on the Gold Coast, where deputising services are well established, and the NSW central coast, where they are not, despite similar demographics.

What is less well known is that most NHDS patients use the service only once a year, about 130 patients per month get cut off because of drug-seeking or other inappropriate behaviour, and 15% to 20% of NHDS visits are billed as non-urgent.

In its advertising, NHDS takes pains to emphasise that patients should have their own GP and attend their regular doctor for follow-up care.