The depth and location of burns are critical to determining how to manage their treatment

The depth and location of burns are critical to determining how to manage their treatment

Australian GPs manage thousands of burns each year. Most are caused by contact with hot liquids, hot objects or an open fire. In young children, common scenarios for burns include cups of tea or coffee pulled off a table, while adult burns are often caused by pouring petrol on to a fire. Other common presentations include chemical and electrical burns, as well as burns caused by sun exposure, extreme cold, and friction.

The ideal first aid for a burn is 20 minutes of cool running water. This is best delivered immediately, but can be effective up to three hours post-injury. While cooling the burn, care must be taken to avoid hypothermia, especially in young children and the elderly.

Remember to cool the burn, not the patient, by keeping the rest of the body warm with a towel or blanket.

After first aid has been administered, the burn needs to be comprehensively assessed and wound management initiated. The management will depend on the depth of the burn and the location on the body.

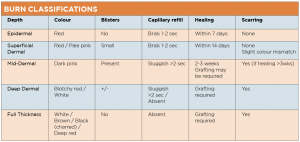

The accompanying table summarises the five burn classifications according to depth: epidermal, superficial dermal, mid-dermal, deep-dermal and full-thickness.1

It is important to note that individual burns are heterogeneous in depth and they are also dynamic. Thus the appearance of the wound can change over a period of time, especially during the first seven days following the injury. A burn may appear to be one depth on day one or two, but this may change significantly after a few days.

MANAGEMENT

To avoid infection, wounds should be kept clean, and antimicrobial dressings used as required.

If the burn is epidermal, (red but not blistered), a wound dressing is not necessary. A simple moisturiser, such as sorbolene, provides adequate management.

If the burn is blistered or skin is lost, a dressing is required to keep the wound clean and moist during healing.

Commonly used dressings include silver dressings such as the Acticoat range and Mepilex range. Alternatively, a Vaseline gauze which contains chlorhexidine, such as Bactigras, can help keep the wound clean and free from infection.

Prophylactic antibiotics are not recommended for burn patients for reasons of antimicrobial stewardship, i.e. to avoid contributing to the high number of multi-resistant micro-organisms. Oral antibiotics should therefore be used only if clinically indicated.

To allow for good wound re-epithelialisation, a longer-term dressing is useful to reduce disturbance to the wound bed. Many dressings can be left on for up to a week.2

Applying the primary dressing is the focus of many clinicians; however the really tricky part is stopping the dressing falling off.

Bandages, while cheap, often stretch and fall off shortly after application. Adhesive woven tapes are often the solution for keeping the dressing in place, and can be cut to size and applied around contours to ensure that normal movement and function are maintained.

SERIOUS BURNS

The ongoing management of serious burns often involves a multi-disciplinary team consisting of doctors, nurses, physiotherapists, occupational therapists, dieticians, speech pathologists, social workers, psychologists, psychiatrists and pharmacists.

Adequate nutrition helps with ongoing wound healing; therefore a high-protein diet should be encouraged. While the skin is healing, the burnt area shouldn’t be static, so the patient should be encouraged to move and perform normal activities, as far as is possible. Slings and crutches are not usually recommended because the skin may heal in a contracted position, causing long-term difficulty with activities of daily living. Physiotherapists and occupational therapists can help manage these issues.

Small burns – less than 1% of the surface area of the body (approximately the size of a patient’s hand) – are often easy to manage, but can also cause significant morbidity. Friction burns from treadmills to the fingers of a child, or contact burns from a motorbike exhaust to the calf are often deep and may require skin grafting. They may also produce a permanent scar, and require long-term management to ensure optimal function.

Burns that take longer than 14 days to heal are a high risk for scarring, and should be referred to a specialist burns unit. NSW Burn Units have excellent digital photo-consultancy services for clinician-to-clinician referral. Photos can be emailed for advice on management and referral pathways.

All photographs must be accompanied by a clinical history, and the Burn Unit involved should be contacted by phone to discuss the case.

To locate and contact burns units nationwide go to anzba.org.au/resources/burn-units/

Siobhan Connolly is chair of the ANZBA Burn Prevention Committee and has worked as the Burn Prevention/Education Officer of the NSW Severe Burn Injury Service since 2005

References:

- NSW Agency for Clinicial Innovation, Clinical Practice Guidelines: Burn Wound Management. 2014, ACI Statewide Burn Injury Service

- Hyland, E.J., et al., Minor

burn management: potions and lotions. Aust Prescr, 2015. 38(4): p. 124-7