One in 25 Australians may have the chronic auto-inflammatory disease, yet it's often under- or misdiagnosed.

Hidradenitis suppurativa (HS), also referred to as acne inversa, is a chronic auto-inflammatory disease that affects between 2% and 4% of the general population.

Despite being a relatively common condition, HS often goes undiagnosed or is misdiagnosed for long periods of time, with an average diagnostic delay of 7-10 years globally1. This delay is hugely significant to patient wellbeing, as not only is HS associated with a huge burden on an individual’s quality of life, it is also associated with several metabolic comorbidities including obesity and diabetes.

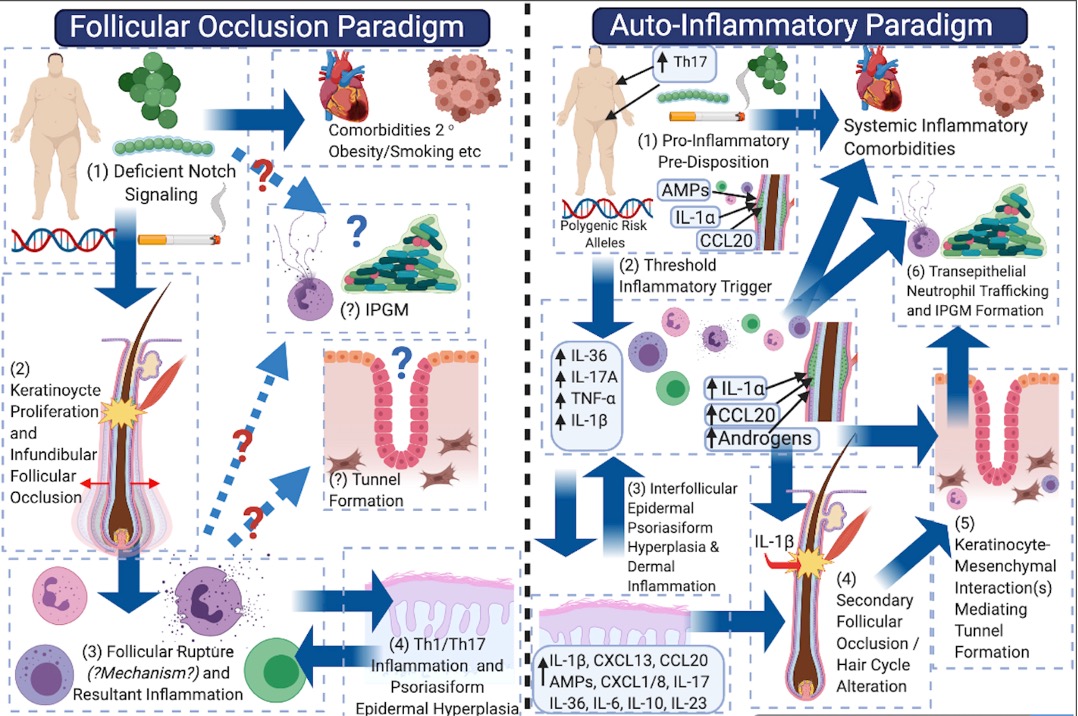

In the past, many considered HS to be an infective disease often secondary to poor personal hygiene, obesity or tobacco smoking. Additionally, follicular occlusion has been thought to be a major driver of disease activity.

Recently, however, this perspective has shifted to recognise HS as a chronic auto-inflammatory medical condition requiring long-term systemic treatment in order to control systemic inflammation, which is the driver of cutaneous disease as well as inflammatory and metabolic comorbidities.

Surgery alone is not curative for HS.

As HS is a systemic inflammatory disease, surgery needs to be combined with long-term systemic therapy in order to achieve reliable disease remission.

Epidemiology and comorbidities of HS

The reported prevalence of HS varies significantly across different studies, with estimates ranging between 0.67%3 and 4%4 with a 3:1 predilection towards women3,5.

The age of onset is bimodal – with a peak in adolescence and young adulthood, and again in women in middle age. It is likely that the published epidemiological data is an under-representation of true disease prevalence given the poorly understood nature of HS and common misdiagnosis of disease.

Additionally, many patients don’t seek medical care because of previous experience of being told there are no effective treatment options, or that this is a disease caused by personal hygiene or lifestyle factors.

The majority of epidemiological data has been examined in Caucasian populations; however, more disadvantaged communities such as Hispanics and African Americans probably have higher, undocumented prevalence of disease.

Asian populations have a different sex ratio from Caucasian populations, with the majority of patients being males, without metabolic comorbidities and more commonly smokers. The majority of genetic studies with familial inheritance has been demonstrated in east Asian cohorts, with a very low percentage of genetic causes seen in Caucasian and European cohorts.

Other pre-disposing risk factors for the development of HS include having a family member with HS and metabolic syndrome, specifically obesity and insulin resistance, as well as hormonal comorbidities including polycystic ovarian syndrome. Acne conglobata is also a common association with HS.

| Comorbidity | Screening |

| Obesity | Weight (kg); BMI; waist circumference |

| Hyperlipidaemia | Lipid studies |

| Insulin resistance / diabetes | Fasting glucose; fasting insulin; HbA1c |

| Polycystic ovarian syndrome | LH, FSH, oestradiol, DHEAS, free testosterone, Free Androgen Index (FAI) |

| Hypertension | Blood pressure monitoring |

| Depression | Mental health screening; DLQI |

Other skin diseases with pathological similarities to HS exist, and these are more thought of as uni-localised forms of HS.

These include pilonidal sinus disease and dissecting cellulitis of the scalp.

In 2015, the British Journal of Dermatology reported that, on average, there was a delay of 7.2 years until an individual was correctly diagnosed with HS1. This is largely due to poor practitioner education and awareness surrounding HS and has huge impacts on patient outcomes and health resources.

HS is quite commonly misdiagnosed as recurrent boils or folliculitis. Unfortunately, this often leads to patients undergoing recurrent unnecessary surgeries or antibiotic treatment regimes.

Further, the misdiagnosis and mistreatment are associated with significant personal and public expense and the misuse of limited healthcare resources.

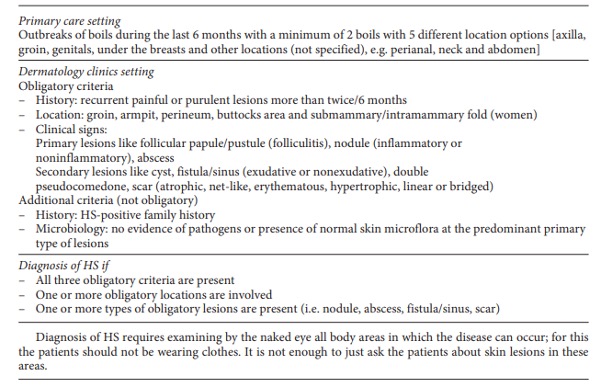

Diagnostic criteria for HS

HS is a chronic auto-inflammatory disease. There are no investigations that can be used to confirm or exclude the diagnosis and, thus, diagnosis relies upon the clinician’s history and examination.

Common symptoms include recurrent inflammatory and painful nodules, malodourous discharge and anatomical disfigurement. Typically, examination reveals multiple inflammatory nodules, abscesses, fistulas, hypertrophic scarring and epithelialised tunnels.

HS primarily affects the intertriginous areas including the axillae, sub-mammary region, and inguinal and peri-anal areas although other areas such as the abdomen and neck can also be affected6.

The diagnosis of HS is based upon clinical criteria. While efforts to develop diagnostic biomarkers are under way, no validated serum or tissue marker can currently diagnose the disease.

The modified Dessau Criteria (Table) is below.

Clinical staging for HS

Staging of HS is most commonly undertaken using the Hurley Score staging system6. This consists of three stages:

Hurley Stage I – solitary or multiple, isolated abscess formation without scarring or sinus tract formation

Hurley Stage II – recurrent abscesses, single or multiple widely separated lesions with sinus tract formation

Hurley Stage III – diffuse or broad involvement, with multiple interconnected sinus tracts and abscesses.

More refined versions of the Hurley staging system include the classification with and without epithelialised tunnels (modified Hurley- BJD 2020) and have been used to guide medical therapy.

Syndromic Forms of HS

For patients with known HS, signs that urgent treatment is needed include fevers, severe acne vulgaris, pyoderma gangrenosum, extreme pain, fluctuations of disease associated with the menstrual cycle, pregnancy and/or breastfeeding7.

Further, it is important to note that rapidly progressing or explosive HS may be representative of a syndromic HS7.

Some of the HS syndromes include PASH (pyoderma gangrenosum, acne, suppurative hidradenitis), PAPASH (pyogenic arthritis, pyoderma gangrenosum, acne, suppurative hidradenitis) and SAPHO (synovitis, acne, pustulosis, hyperostosis, osteitis). These syndromes are rare but they are important to recognise as the treatment will differ compared with standard non-syndromic HS8.

| PASH | pyoderma gangrenosum, acne, suppurative hidradenitis |

| PAPASH | pyogenic arthritis, pyoderma gangrenosum, acne, suppurative hidradenitis |

| SAPHO | synovitis, acne, pustulosis, hyperostosis, osteitis |

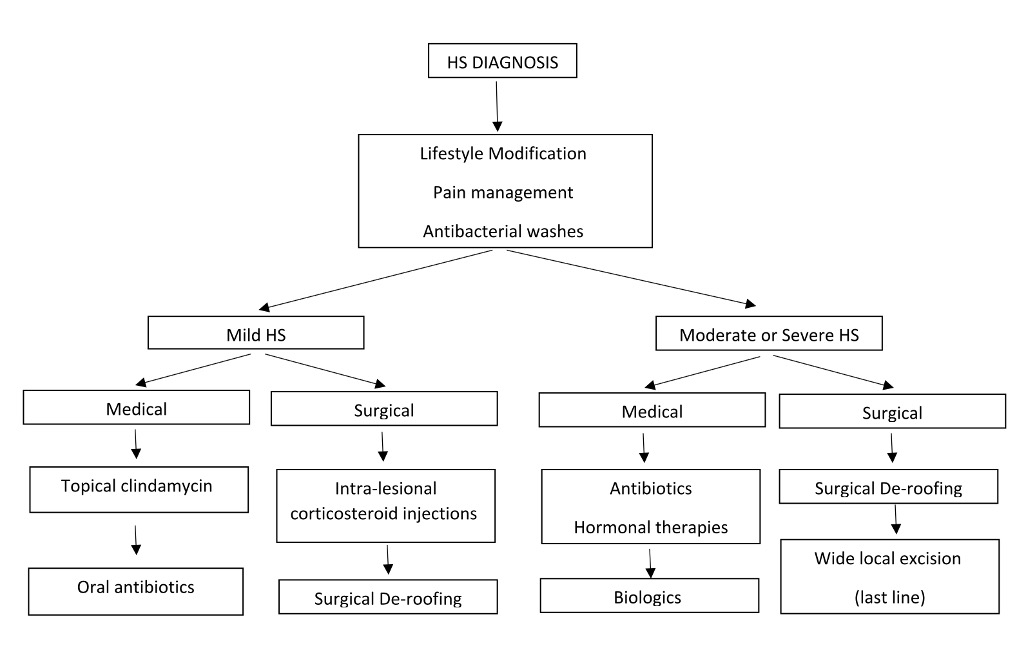

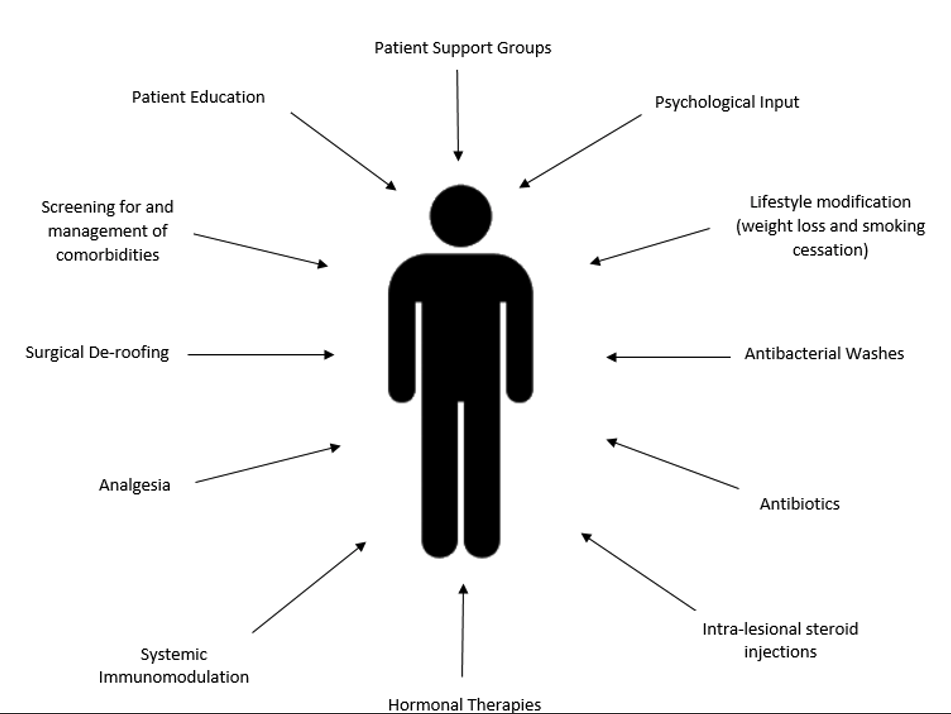

Management of HS

Symptomatic management of HS largely revolves around pain control.

Over the counter analgesia including paracetamol and ibuprofen is often not sufficient and patients may require short-term courses of opioid medications to manage a flare of HS. Some cases may benefit from gabapentin. Intralesional corticosteroid injections (triamcinolone) into acutely inflamed lesions have been demonstrated to swiftly reduce erythema, suppuration and size of the lesion9 and thus also can reduce pain for the patient. Addressing existing comorbidities such as obesity, smoking and diabetes will contribute to disease control but are successful only in conjunction with systemic therapy.

Topical therapy

Topical washes (such as pHisoHex) have not been demonstrated to improve disease activity but, in our experience, patients report some improvement in malodour after using these skin cleansers.

The only topical antibiotic that has been studied in HS patients is clindamycin 1% solution. A 12-week randomised, placebo-controlled trial demonstrated a reduction in pustules but no improvement to inflammatory nodules or abscesses10.

Antibiotics

Systemic antibiotics have been considered the primary medical treatment option for HS patients for many years.

These include monotherapy with tetracyclines doxycycline or minocycline as a first line, combination therapy with clindamycin and rifampicin as second line and combination therapy with moxifloxacin, metronidazole and rifampicin as third line9.

Other antibiotic therapies include dapsone and IV ertapenem6; however, they should be reserved as last-line options given the significant side-effect profile they are associated with and the associated concerns regarding antibiotic resistance.

Due to the chronic nature of HS, many patients will require long-term systemic immunosuppressive therapy to control their disease.

Methotrexate and azathioprine are not recommended due to their lack of efficacy9 while data surrounding cyclosporine use has been largely inconclusive9.

Short-term courses of systemic corticosteroids may be beneficial for symptomatic management during acute flares of HS9 but are not recommended as a long-term therapy because of the associated adverse effects including osteoporosis and weight gain.

Immunomodulatory therapy

Ultimately, the most effective medical therapy in managing HS is immunomodulation or immunosuppression with biologic medications.

Adalimumab (Humira) (TNF-a inhibitor) has been demonstrated to improve both disease severity and patient quality of life for those with moderate to severe HS9.

At present, adalimumab is the only biologic medication available through the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme (PBS) in Australia; however, clinical trials into other biologic medications including anakinra (IL-1 inhibitor), ustekinumab (IL-12/IL-23 inhibitor) and infliximab (TNF-a inhibitor) are promising9,11. These medications are sometimes accessible via compassionate supply and clinical trial programs and should be considered for patients who are not responsive to adalimumab.

Additional systemic medical treatments for HS include the oral contraceptive pill, metformin and spironolactone, particularly for females with HS who report fluctuations of disease associated with their menstrual cycle, pregnancy or breastfeeding.

Surgical therapies for HS:

Surgical management for HS as a stand-alone therapy is not a long-term curative option.

Surgery can be a useful adjuvant in limited disease (Hurley Stage II) for acute pain relief (incision and drainage) although recurrence is the norm.

Ultrasound-guided de-roofing procedures are a tissue-saving technique for the removal of epithelialised tunnels. This is most effective as an adjuvant to medical anti-inflammatory systemic therapy.

Wide excision and skin grafting can be complicated by infection, dehiscence, prolonged wound healing (6-9 months) with recurrences post-operatively. Hence, wide excision should be reserved only for the most severe cases; that is, those that are non-responsive to maximum medical therapy.

Conclusion

Early recognition and diagnosis of HS is extremely important in improving the quality of life and disease burden experienced by patients.

Once HS has been diagnosed, timely referral to a dermatologist who manages HS is helpful in improving patient outcomes. Treatment should be holistic and should include lifestyle, medical and surgical options to increase the likelihood of long-term disease remission. Further, the screening for and management of associated co-morbidities is essential in achieving optimal patient care.

References

- Saunte, D.M., Boer, J., Stratigos, A., Szepietowski, J.C., Hamzavi, I., Kim, K.H., Zarchi, K., Antoniou, C., Matusiak, L., Lim, H.W., Williams, M., Kwon, H.H., Gurer, M.A., Mammadova, F., Kaminsky, A. Prens, E., van der Zee, H.H., Bettoli, V., Zauli, S., Hafner, J., Lauchli, S., French, L.E., Riad, H., El-Domyati, M., Abdel-Wahab, H., Kirby, B., Kelly, G., Calderon, P., del Marmol, V., Benhadou, F., Revuz, J., Zouboulis, C.C., Karagiannidis, I., Sartorius, K., Hagstromer, L., McMeniman, E., Ong, N., Dolenc-Volc, M., Mokos, Z.B., Borradori, L., Hunger, R.E., Sladded, C., Schenfield, N., Moftah, N., Emtestam, L., Lapins, J., Doss, N., Kurokawa, I. & Jemec, G.B.E. (2015). Diagnostic delay in hidradenitis suppurativa is a global problem. British Journal of Dermatology, 173(6): 1546-1549.

- Frew, J.W. (2020). Hidradenitis Suppurativa is an autoinflammatory keratinization disease: A review of the clinical, histologic and molecular evidence. JAAD International, 1(1): 62-72.

- Vekic, D.A. & Cains, G.D. (2017). Hidradenitis Suppurativa – Management, comorbidities and monitoring. Australian Family Physician, 46(8): 584-588.

- Jemec, G. B., Heidenheim, M. & Nielsen, N. H. 1996. The prevalence of hidradenitis suppurativa and its potential precursor lesions. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology, 35, 191-194

- Garg, A., Kirby, J.S., Lavian, J., Lin, G. & Strunk, A. (2017). Sex- and Age – Adjusted Population Analysis of Prevalence Estimates for Hidradenitis Suppurative in the United States. JAMA Dermatology, 153(8): 760-764.

- Zouboulis, C.C., Del Marmol, V., Mrowietz, U., Prens, E.P., Tzellos, T. & Jemec, G.B.E. (2015). Hidradenitis Suppurative/Acne Inversa: Criteria for Diagnosis, Severity Assessment, Classification and Disease Evaluation. Dermatology, 231(2): 184-190.

- Fernandez, J.M., Hendricks, A.J., Thompson, A.M., Mata, E.M., Collier, E.K., Grogan, T.R., Shi, V.Y. & Hsiao, J.L. (2020). Menses, pregnancy, delivery and menopause in hidradenitis suppurativa: A patient survey. International Journal of Women’s Dermatology, 6(5): 368-371.

- Gasparic. J., Riis, P.T. & Jemec, G.B. (2017). Recognizing syndromic hidradenitis suppurativa: a review of the literature. Journal of The European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology, 31(11): 1809-1816.

- Alikhan, A., Sayed, C., Alavi, A., Naik, H.B., Orgill, D. & Poulin, Y. (2019). North American clinical management guidelines for hidradenitis suppurativa: A publication from the United States and Canadian Hidradenitis Suppurativa Foundations. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology, 81(1): 91-101.

- Clemmensen, O.J. (1983). Topical treatment of hidradenitis suppurativa with clindamycin. International Journal of Dermatology, 22(1): 325-328.

- Frew, J.W. & Krueger, J.G. (2021). What’s in the pipeline for hidradenitis suppurativa? Emerging and novel therapeutics. Drugs of the Future, 46(1): 43.