Feeding toddlers can be challenging for parents, particularly when there is so much conflicting information available, writes Eve Reed

How do you advise parents when they tell you their one or two-year-old has suddenly become cautious, fussy, erratic and unpredictable with their eating?

They tell you that their toddler will eat a lot at one meal and hardly anything at the next, eat only one food sometimes and everything you offer at other times and won’t try new foods. Until now, they have felt successful in feeding their almost-toddler, who has more or less eaten whatever they have been offered.

They are describing common toddler eating behaviours that you have probably heard about many times from parents.

Parents who don’t know what is going on with their toddler can become concerned and anxious if they are not aware that these are normal toddler eating behaviours.

They can become pushy and put unnecessary pressure on their child to eat foods that they are not ready to eat or to eat more or less than they are hungry for. Pressure can include bribing, coaxing, forcing, distracting and “encouraging”.

This results in unpleasant mealtimes which can lead to the toddler becoming anxious and defiant at mealtimes and around food in general.

THE TODDLER STAGE

Physically, the toddler stage is when a baby can get around by crawling or walking, in order to explore their world. Emotionally, socially and cognitively, it’s when a child is actively in the process of separation and individuation.1 They are finding out that they are a separate person by exploring their surroundings, and by saying “no” a lot.

Toddlers want more control over their lives and start to test limits. It is important to help the toddler to learn through experience and to develop autonomy. Parents can help this process by not trying to control their toddler and not letting the toddler control them. Parents need to offer structure and limits in all aspects of a toddler’s life.

SATTER DIVISION OF RESPONSIBILITY

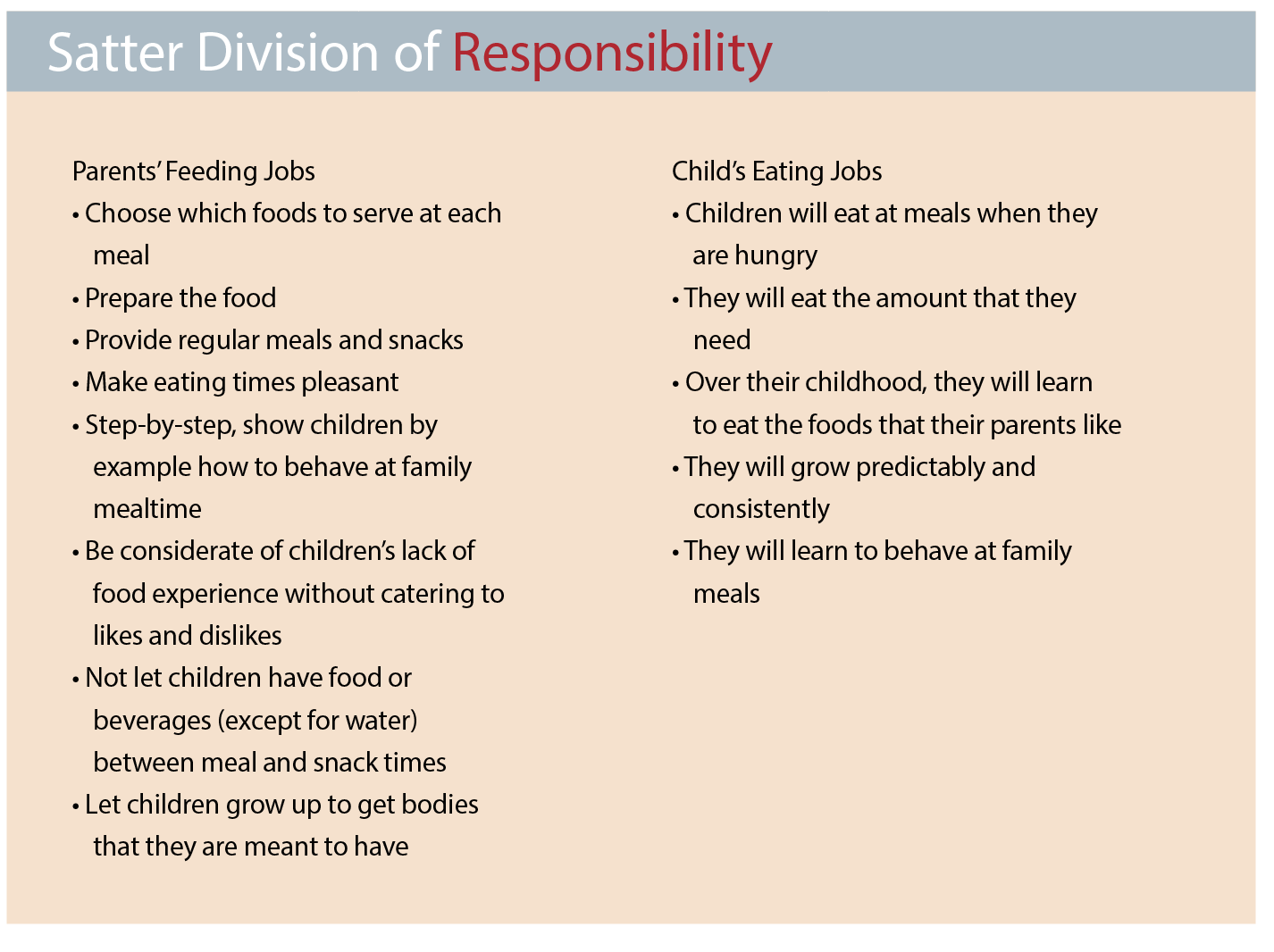

When it comes to feeding, what is known that following the Satter Division of Responsibility2 in feeding (sDOR) is going to make sure that feeding goes smoothly. For the toddler, and for all ages that follow, sDOR looks like this:

• The parent is responsible for the what, when and where of feeding

• The child is responsible for the how much and whether of eating

To clarify, there is a clear division between the parents’ feeding jobs and the child’s eating jobs.

The toddler phase is a good time for you to discuss where parents are going with feeding. The sDOR describes “how” to feed children in order for them to remain or become competent eaters.3

When parents feed their child according to the sDOR their child will remain or become competent eaters who:

1. Feel good about eating

2. Are comfortable with unfamiliar food

3. Go by feelings of hunger and fullness to know how much to eat and how to grow

4. Enjoy family meals and behave well there

These are the practical steps you can suggest to parents in order to implement the sDOR in feeding their toddler:

• Maintain structure: Offer foods at five or six planned meals and snack times. Don’t let children eat or drink, apart from water, in between as this will lessen their hunger at meals.

• Be considerate without catering: Offer the same food for everyone. Make sure there is at least one food on the table that the toddler will eat if they are hungry. This is usually bread, plain rice or plain pasta. Parents don’t need to limit the variety of foods they are eating themselves as this limits the child’s exposure to foods and encourages fussy eating.

• Eat with your child as much as possible: Family meals give children the opportunity to learn to eat what their parents enjoy eating. Children who have family meals do better nutritionally, emotionally and socially.4

• Put the food on the table rather than plating the meal: This gives children appropriate control over what they choose to eat from what parents offer.

• Let the child decide how much they want to eat: Trust the child’s appetite. Once the food is on the table, don’t put pressure on the child to eat or not to eat a certain amount of food. Parents who are more controlling about food tend to have heavier children.5

It is at this stage that toddlers are at risk of learning to eat for emotional reasons. They are active, demanding and can get upset easily.

It is tempting for parents to give food as a reward, distraction or to soothe feelings. However, this is not going to help children eat according to their hunger and satiety cues and can lead to accelerated weight gain.

Feeding a child and the child learning to eat what their parents eat is a process that begins at birth and ends when a child leaves home. It is unrealistic for parents to expect that a child at the toddler stage will have mastered the process of learning to eat a wide variety of foods.

CHECKING GROWTH

Growth is a sensitive predictor of nutritional status, health and psychosocial environment. Assessment of growth is an important first step in deciding whether the child actually has a nutritional or medical problem.

Normal growth will indicate that a child has an adequate energy intake, however it is not going to identify micronutrient deficiencies. If the child’s growth is normal, you can reassure parents that the child is eating enough food and has a normal appetite.

Parents who perceive their child as underweight are more likely to pressure their child to eat and parents who perceive their child as overweight are more likely to restrict a child’s intake so it is important to assess growth at the outset.

Growth assessment involves measuring both height and weight over a period of time. We need to be able to assess whether the child’s weight is tracking more or less along a consistent percentile. Has there been weight acceleration or weight faltering?

For children aged zero to two years the recommended charts to use are the WHO growth charts http://www.who.int/childgrowth/standards/en/. For children aged two to 18 years it is recommended to use the in US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention charts, (http://www.cdc.gov/growthcharts)

These charts are suitable to be used for all ethnic groups and for breast and formula-fed infants.

For parents who are concerned about their toddler’s eating, a thorough growth assessment is the first, essential step.

WHAT IS NORMAL GROWTH?

Most children’s serial height and weight will track along or parallel to a particular percentile. During the first year of life, it is not unusual for weight to cross one or two percentiles. Usually, height and weight are track along similar percentiles, but not always. This is normal growth. Most children who present as poor eaters will have a normal growth pattern.

Some parents think that if their child is growing below the 50th percentile, their growth is not “normal” or that their child is underweight. As health professionals, we need to help parents understand growth charts and what normal growth is.

Once you have established that the child is growing well and has no major health problems, you can reassure the parent/s that despite their concerns about their toddler’s eating they are eating enough food to grow to have the body size they are meant to have genetically.

ACCELERATING OR FALTERING WEIGHT

When a toddler’s weight is deviating from their normal pattern, as described above, we need to find out what is interfering with the child’s growth, before intervening.

Some of the possible interferences are:

• A medical issue that complicated eating and/or growth early on and continues to cause problems: For example, a child who had recurrent illnesses in the first year of life which caused poor weight gain. The parents continue to be anxious and feel that their toddler doesn’t eat enough now as a toddler. They continually try to get their child to eat, which causes the toddler to be anxious at mealtimes. This can lead to the child eating less than they need and continue to grow poorly.

• A child with a challenging temperament: For example, a child that tests the limits by asking for food constantly between meals and has tantrums when he is not given what he wants. Some parents find this behaviour challenging and give food instead of insisting on eating only at planned meal and snack times. This can lead to weight acceleration as the child is eating whether they are hungry or not.

• The way parents approach feeding: For example, if parents have been told that their infant is “too big” they may have been restricting the child’s intake. Children whose intake is restricted at mealtimes, end up eating more than they need when they get a chance. This can lead to weight acceleration.

• Developmental: For example, a toddler may have trouble mastering feeding themself, and insists on being fed. The parents may find it easier to feed the toddler instead of helping them learn to feed themself.

• Something nutritional: For example, the toddler could be drinking so much milk that the milk replaces other foods, leading to anaemia. When they don’t eat at mealtimes, they are given more milk to make up for not eating. Drinking milk is easier for the child than sitting at the table and eating.

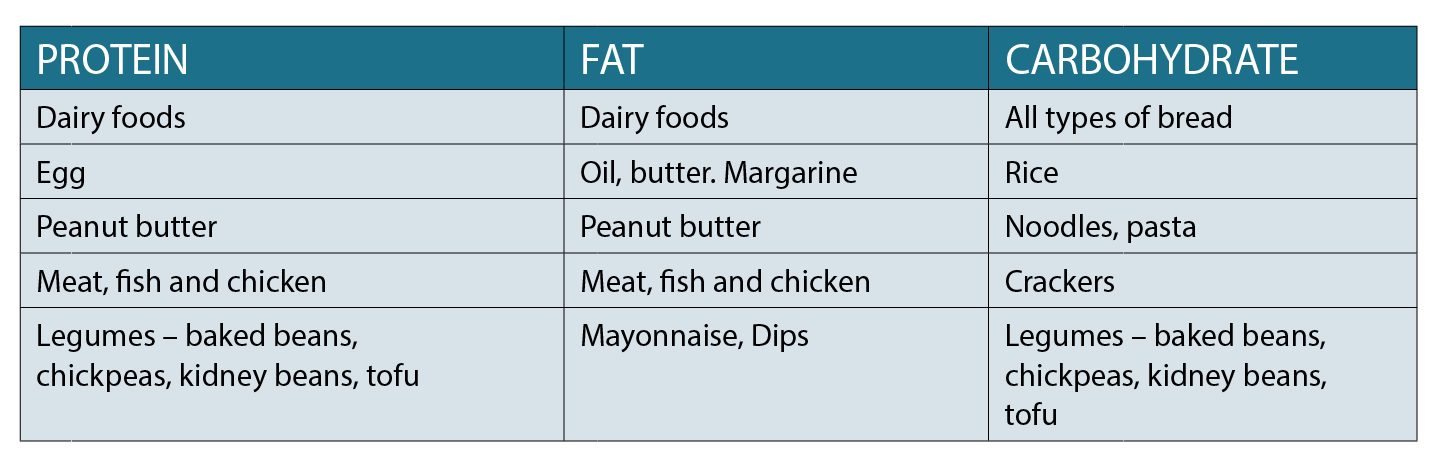

Healthy toddlers, like all children, will meet their nutritional requirements if they eat foods from the five food groups: fruit, vegetables, grain foods, dairy foods, meat, fish, chicken and egg, nuts and seeds, legumes, tofu.

However, it is possible to meet requirements on a more self-restricted diet. Vegetables and red meat are the most common foods that toddlers are not keen on eating. However, if they are eating some fruit, they will be getting similar nutrients as they would from vegetables.

For those not eating any red meat, it may be more difficult to meet iron requirements. Iron-fortified breakfast cereals, wholegrains such as oats and wholegrain breads as well as legumes such as chickpeas, kidney beans and baked beans all provide iron.

It is very rare for a child not to be meeting their protein requirement. Apart from meat, dairy foods, eggs, nuts and legumes are all good sources of protein. Foods made from wheat such as bread and crackers contain about 10% protein and contribute a significant amount of protein to toddlers’ diets.

In order to provide plenty of opportunity for toddlers to learn to like the foods their family enjoys, parents need to offer five or six structured meals and sit-down snacks each day. At each of these meals and snacks, offer foods that contain protein, fat and carbohydrate.

Fat is important in toddlers’ diets as it provides a concentrated source of energy and helps them fill up without having to eat a large amount of food. It also provides essential nutrients.

A typical day may look like this:

Breakfast: Cereal and milk and fruit

Morning tea: Raisin toast with butter

Lunch: Tuna, bread, mayonnaise and cut up raw

vegetables

Afternoon tea: Yoghurt and fruit

Dinner: Spaghetti, bolognese sauce and grated cheese and salad

Bedtime snack: Depending on a child’s daily routine, there may be time/need for a snack before bed. For toddlers this could be milk from a cup or fruit or yogurt

Feeding toddlers can be challenging for parents, particularly when there is so much conflicting information available.

As health professionals, we can help parents feed their children so that they become competent eaters. Implementing the sDOR is the basis of competent eating.

Suggested reading: Ellyn Satter. Feeding with Love and Good Sense: 18 months through to six years Kelcy Press 2013. The booklet can be bought in Australia on the website: https://www.familyfoodworks.com.au/shop/

Eve Reed is paediatric dietitian based in Sydney. She has been a senior member of the Department of Nutrition and Dietetics at the Children’s Hospital at Westmead in Sydney as well as the owner of her own paediatric nutrition practice, Family Food Works www.familyfoodworks.com.au. Eve has co-authored three books on children’s nutrition and health as well as an ebook on Fussy Eating. She is a faculty member of the Ellyn Satter Institute, whose mission is to support parents in feeding their children.

References:

1. Mahler, M.S. (1963) Thoughts about development and individuation. Psychoanalytic Study of the Child. 18:307-324.

2. Satter EM. The feeding relationship. J Am Diet Assoc. 1986;86:352-356.

3. Satter EM. Eating Competence: definition and evidence for the Satter Eating Competence Model. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2007;39:S142?S153.

4. Casa The National Center on Addiction Substance Abuse at Columbia U. The Importance of Family Dinners II. 2005;

5. Birch LL, Fisher JO, Davison KK. Learning to overeat: maternal use of restrictive feeding practices promotes