Patients are at four times the risk in the week after an endoscopy, and three times the risk after vascular surgery.

In the week following outpatient surgery, a patient is up to four times more likely to have a heart attack, and the type of anaesthesia and procedure appear to play a role.

The Norwegian study of more than 6000 patients aged over 40 found that having a gastrointestinal endoscopy was associated with a four times higher relative risk of heart attack in that first week.

Vascular surgery had triple the risk, and for urological/gynaecological procedures the risk was twice as high.

“It is important that clinicians, while performing particularly highly invasive and therefore risk-prone procedures, consider every possible preventive strategy to decrease excess risk by following preoperative health assessment or risk stratification before planning a procedure and also when monitoring after the procedure,” the authors wrote in Heart.

The study suggested that, overall, outpatient procedures were generally safe in terms of the post-operative risk of heart attack, but orthopaedic, gastrointestinal endoscopy, urological/gynaecological and vascular procedures were associated with short-term increased risk of acute myocardial infarction, the authors wrote.

The short-term risk of heart attack was higher after surgical procedures performed under general or regional anaesthesia compared to local anaesthesia, the authors said in the study, which analysed 1000 procedures under local anaesthesia and 7000 under regional/general anaesthesia,

They also found an increased risk of heart attack after some ENT-mouth, urological/gynaecological and vascular procedures performed under local anaesthesia.

Overall, the absolute risk of heart attack is 0.73% for people in Sweden, but in the week following the procedure, this jumped to 0.80% in those having gastrointestinal endoscopies and 0.87% for vascular procedures.

Commenting on the study, senior cardiologist at Sydney’s St Vincent’s Hospital Professor Jason Kovacic?said the study showed that most procedures were very safe, but as the magnitude of the surgery escalated, so did the short-term risk.

“Our job as physicians is balancing risk and reward and risk and benefit and this paper nicely shows that grading of risk. The more major the surgery, the more the risk goes up,” the Victor Chang Cardiac Research Institute chief executive told TMR.

“It underscores that it’s a continuum of risk. If you’re just having a tiny mole taken out on your forearm, then it’s extremely unlikely that anything’s going to happen as a result of getting 1mL of local anaesthetic and something cut out.

“Whereas if you’re going to have a massive hip replacement, and someone has very poor exercise capacity and is getting chest pain, then that’s pretty likely to end in complications.”

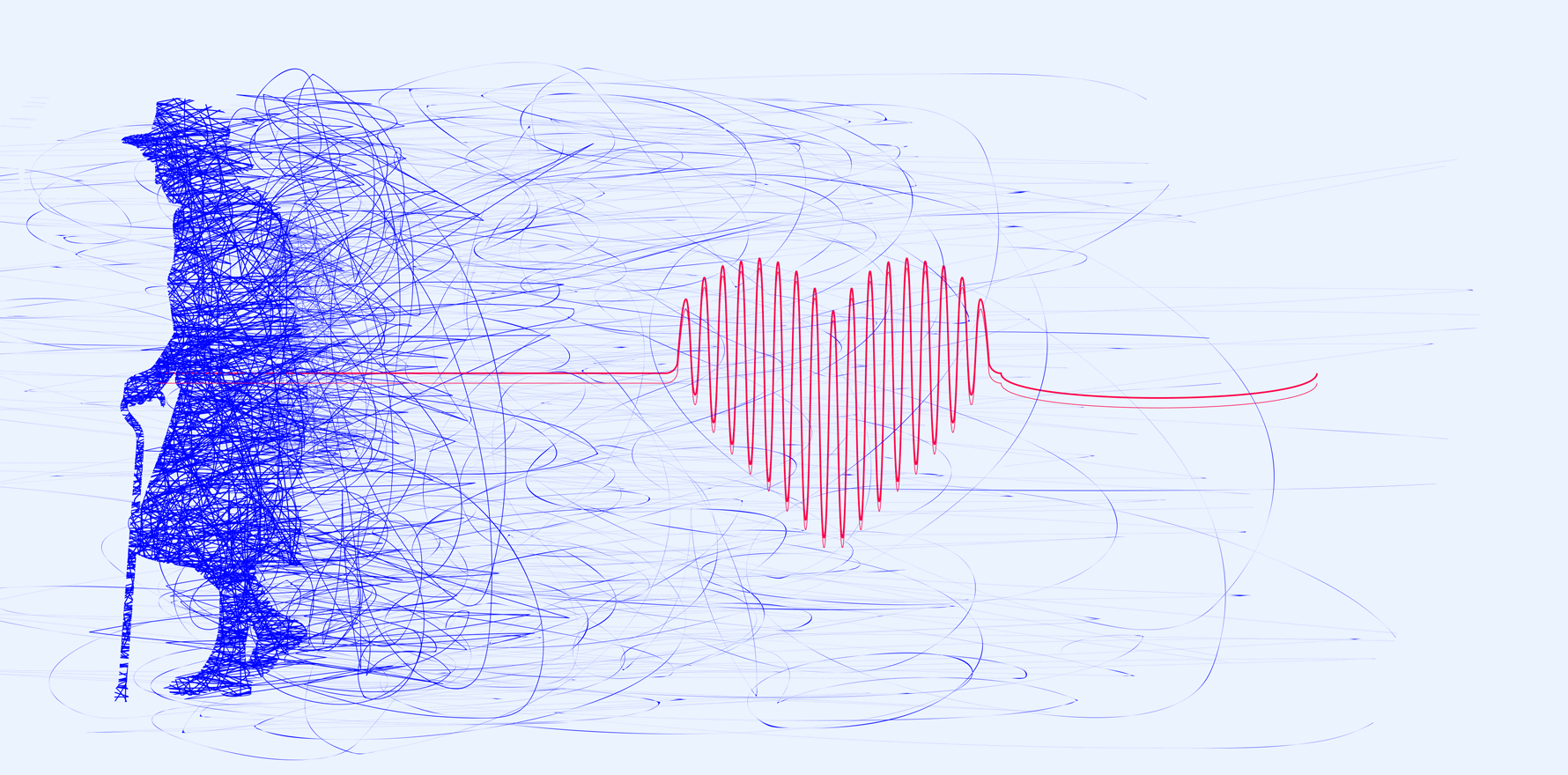

The average age of the study participants was 74, and Professor Kovacic said it was not surprising that the study found that older people who had general anaesthesia had an increased risk of heart attack.

“Be cognizant that if you’re putting a patient in their 70s through a significant surgery, then it’s important to consider whether they are optimised medically going into that, and whether there is any sort of preoperative assessment necessary.

“It does underscore that it’s worth a clinical history and if someone’s getting severe chest pain or angina then we need to think carefully about sending them off for a hip replacement in the context of that.”

One limitation was that subject numbers in some surgical categories were small. For example, only 15 of people had general anaesthesia for vascular surgery.

“It’s important to bear in mind that given that this is a population-wide study over eight years, the total numbers in some of these groups are still very small and it’s important that we keep those results in perspective.

“The numbers of events we’re seeing here are quite low, which should be very reassuring to us all.”

Professor Kovacic said it was important to make a joint decision with the patient, family, physician and surgeon about whether surgery was in the best interests of the patient.

For some patients the risks of not having surgery would outweigh the risk of having a heart attack, while some semi-elective procedures could potentially be managed in other non-surgical ways if the patient was high-risk, he said.

Professor Kovacic said it was well known that any major life stressor such as major surgery or surviving a natural disaster increased the risk of heart attack in the following days.

The researchers said a patient’s health most likely played a key role in the overall risk of heart attack after surgery.

“The typical AMI (type 2) caused by anaesthesia is generally due to myocardial ischaemia related to drop in blood pressure in vulnerable patients. Probably, it is the type of surgical procedure and the patient’s physical health which pose the most risk, rather than anaesthesia per se.”

They said the short-term increased risk may be due to significant inflammation after an extensive procedure, “altering the balance between coagulation and fibrinolysis and causing myocardial infarction through atherothrombosis”.

Another possible explanation may be that antiplatelet medication had been stopped before surgery, increasing the risk of heart attack.

“Furthermore, an increased risk observed in relation to procedures involving gastrointestinal endoscopy and ENT-mouth might be due to autonomic stress caused by the investigation, leading to a surge of catecholamines and cortisol and to coronary vasoconstriction and plaque instability, which in turn might trigger an AMI in vulnerable patients,” they said.