EMRs, the MHR, interoperability, the patient-centric imperative? Digital health has so far promised big and delivered little. So where is all this heading for GPs?

EMRs, the MHR, interoperability, the patient-centric imperative? Digital health has so far promised big and delivered little. So where is all this heading for GPs?

At last month’s launch of the Australian Digital Health Agency’s consultation on interoperability, the agency’s chief executive, Tim Kelsey, declared that Australia was now a world leader in digital health.

He listed the My Health Record (MHR) and the legislation that enabled it to occur as evidence of our rapid progress and leadership in patient empowerment. And having declared the MHR a success (so far, at least) he launched the next phase of the agency’s program to revolutionise Australian healthcare, a consultation phase on interoperability.

Interoperability is how all the parts of the healthcare system will talk to each other, and seamlessly and securely share vital patient data. It’s the healthcare system’s nirvana, if anyone can actually crack it. Done well, it will certainly save lives and a lot of money.

For GPs, it would mean you can talk smoothly through your patient management system to pathology, imaging, specialists, allied health, hospitals (including great discharge summaries always) and, yes, your patients. No more faxes, no more patients going missing or turning up having forgotten their discharge summary. You get the picture.

Kelsey skilfully painted it to a bevvy of government and private health providers and vendors in the room for the launch of this phase of the agency’s work.

It was all going swimmingly until one invited global digital health guru got up and said almost the opposite of what Kelsey said. Grahame Grieve, who is the founder of global web sharing health standard, Fast Interoperability Healthcare Resource (FHIR pronounced FIRE not FUR!), who is recognised around the world and feted as the expert on healthcare interoperability, told us all that in digital health Australia was now, in fact, “at the back of the pack”.

Confused? You’re not alone. Both Kelsey and Grieve are passionate hard-working believers. But both are facing the world from very different perspectives, and face different, but probably equally challenging, problems.

Kelsey is leading an agency that is charged with digitally transforming a health system that is highly fragmented, politicised (both at a state and federal level) and complex. And when he came to it, it was hugely messed up. He wants what Grieve wants, which is “real” interoperability.

But Kelsey has many political and regulatory masters, and he has to please nearly all of them if he is to keep his job and enough continuity to actually get stuff done. Kelsey’s degree of difficulty is in the high nines.

If we are to believe a number of different surveys, the MHR, for most GPs, has been distressing. Not only was “opt-in” viewed as a unacceptable breach of patient trust, the system, so far, is a pain to update, and not useful on a day-to-day basis.

The concept seemed good, and for political reasons the AMA and the RACGP came out in support of the MHR. But behind closed doors there remains much cynicism and distrust.

Disenfranchising doctors is not what the ADHA wanted at all. But in the end it was a trade off. The agency had to get the MHR over the line in order to keep going. There had to be a success to offset where there had been so much disappointment and failure in the past. There had to be proof that the agency could get stuff done. There had to be trust from the government, the holders of the purse strings.

Tim Kelsey keeps his cards close to his chest. But he knows the MHR isn’t perfect in lots of ways. It’s outdated even. He would likely have anguished over the issues it created among GPs especially. But the MHR had such a bad birth and history before he arrived that he had to somehow stem that bleeding wound and gain some credibility in the minds of his masters.

The most interesting question that we would love to get a non-political answer on is: Did this last two years obsessing over the MHR mean we lost valuable focus and time on more pointed and effective solutions to interoperability?

Did we, as Grieve told the elite of Australia’s digital health community, do a bit of fiddling while Rome, namely interoperability, was burning in the background?

Grieve travels the world now talking to and advising healthcare regulators in many different countries, with vastly different economies, cultures and motivations for fixing their health systems. Just a few weeks ago he was asking pointed questions of Jared Kushner, whom US President Donald Trump had, in his wisdom, put in charge of fixing the biggest health interoperability mess in the world – the US veterans healthcare system.

A couple of weeks after that he was in China, and then soon after in India, advising the healthcare leaders in those countries. Grieve has a perspective others just don’t have. It’s why Kelsey invited him to his launch, although there was always the risk he might go way off the ADHA’s script, Kudos go to Kelsey for risking it.

So who is right?

What Grieve would say is: “It doesn’t matter. We are where we are.” You suspect Kelsey might be on that page also. And this surely is a good thing.

If you believe Grieve, we are at least at the start, finally, of an earnest and honest attempt to sort out how we communicate important patient data much better. Late, but nonetheless committed and proceeding with all the ADHA’s firepower now turning to this issue.

If you believe Kelsey, the MHR is an important stake in the ground for our future of digital health, which needed the attention it got. He might also say that the MHR is an important part of the interoperability picture.

Kelsey has a lot of fierce detractors in health-technology land. But some of what he’s done and says stacks up, even if the MHR doesn’t go that much further in terms of its actual utility to our digital health future:

• The legislation around patient empowerment that goes with the MHR is unique worldwide and an important platform for any work we will now do around the concept of being “patient-centric”.

• The hype and PR around the MHR program has put digital health on the patient map and focussed many minds on the potential and aspiration of digital health.

• There are some neat examples emerging of the MHR being very useful. eg, during the recent floods in northern Queensland where patients had to use different pharmacies and different doctors and the MHR solved a lot of the medication issues.

• The ADHA appears to have the attention, the confidence, and, in some cases, the trust of many of the stakeholders that count in getting digital health sorted – especially in government. If we look back to the damage that NEHTA, the ADHA’s predecessor agency, did to that confidence and trust, our relative position with regards to getting things done is much better than it was.

In a strange way, Grieve and Kelsey, probably the two most important people directing our digital health future today, are in some form of agreement. Both have energy and purpose which looks like it finally might be aligning. We can but hope.

So what’s in all of this for GPs?

GPs are the major node of leverage for important patient information exchange in a connected future health system, especially now we are moving from an acute-care-based system to one that will need, mainly, to manage chronic care.

Think about those points of leverage that pass through, emanate from, or have their end point with a GP. There’s medicines management, pathology testing, imaging, referral to a specialist, pharmacy, hospital discharge management, data to any number of related allied health professionals in chronic-care teams, aged care institutions, and so on and on. GPs are the most important node in a connected health system and if somehow, they are able to seamlessly talk to all these other nodes in the not too distant future, they won’t recognise themselves. Certainly, there should be much more time to do medicine and much less time faxing, re-entering data, and ringing people for appointments, results and other menial tasks.

And although there is a long way between that connected world, and where they are now, GPs in Australia, are at least highly computerised already. On every desk, Best Practice, MedicalDirector, and a few other vendor systems, are reasonable platforms from which such communication will eventually be able to launch.

Indeed, all these systems already do a fair bit of talking electronically to other systems. Just not enough, and very inefficiently as a result of a history that has us with a mix of multiple formats for electronic messaging, faxing and phoning. And there is still no one home electronically at half of our specialist cousins (ie, many don’t even have a computer on their desks!), and various other roadblocks of circumstance.

Which brings us full circle back to Grieve, his magic of FHIR, and where healthcare data sharing technology is heading all over the world. If it was actually magic, you could describe FHIR as a universal and secure translator of messed up and complex healthcare patient data between any system that wants to put FHIR on its in/out pipe and has an internet connection.

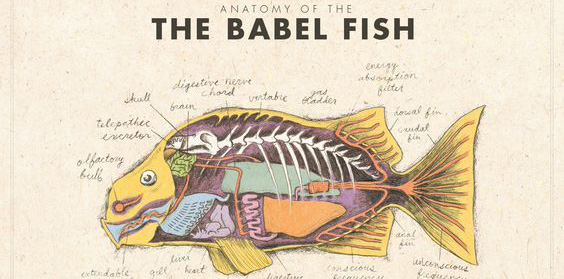

Like the Babel fish in Douglas Adams’ Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy, which famously lived in your ear and universally translated every language in the galaxy, with FHIR every system and database could talk to the other, no matter where they were. So a GP’s patient management system, which has the most up-to-date and accurate information of any database on a particular patient in the country, could talk to a hospital, a specialist, or a pathology lab instantly.

But most importantly, it will talk to a patient’s mobile phone (and any other of their devices), securely, and they will have an accurate medical record which updates in real time.

This, of course, would mean that much of the MHR will become redundant. Not all of it, notably, as the MHR collects some information that is really important for a patient and quite hard to get. But who knows.

This form of distributed data sharing between healthcare providers and patients is starting to happen already, and very effectively in other countries.

In the US a few weeks ago, the government even turned around and announced its intention to mandate that all providers, within a reasonable period of time, make certain that FHIR is installed on their in and out pipe, so all points of the system can talk to each another.

And in case you haven’t heard, technology titans Apple and Google already are imbedding FHIR into the communication protocols of their operating systems and mobile phones. That’s how big FHIR has become overseas.

Which might make you wonder what our position on FHIR in Australia is today. Surely, given that Grieve invented FHIR here in Australia, we are ahead of the curve, right?

Not quite.

And this is where you can forgive Grieve for being a little annoyed at the precedence given to the MHR project by ADHA.

In the US, the government’s position on FHIR is all about empowering patients with their own data. Hence, not only do providers have to be able to share data, but they must be equipped to share it meaningfully with their clients. That is what the US is thinking when it thinks about going patient-centric.

In Australia, it could be argued that the MHR could do a lot of what FHIR is being set up to do in the US – empower patients with their own data. Some might even go to the far ends of such an argument and say that, given the MHR is a central hub of collection of most of a patients important data, it might be that this central source of data could serve as a de facto node in the system.

If everyone connects to the MHR, then they can download and upload all the information to make interoperability work.

Hopefully readers will recognise the flaws in such a concept. It’s centralised so it’s a giant single point of failure – for security and for communication, as every vendor will have to build to what the MHR master data centre requires. It’s a very 1980s IT architecture.

FHIR could help, of course. Everyone could put FHIR on their in/out pipe and so could the MHR. If it’s a universal translator then problem solved, right?

But if you can use FHIR to fire up live and accurate databases such as a GP patient management system, or a pathology lab, which then talk directly to a patient, which is likely to be better? And which is easier to roll out and manage over time, more flexible for the patient and far more secure?

If you’re confused, it’s FHIR being used to empower all our distributed data sources in health, that will then be able to talk to a patient with live accurate data, when the patient needs it, and how they need it, that is really a much better way to go in time.

In some ways, the US decision to make FHIR a mandated standard is a huge stake in the ground for the future of interoperability. And though everyone loves to say don’t follow the US, it’s a terrible healthcare system, the best parts of it are also the best in the world.

If the US is going this way on interoperability, we should probably be asking ourselves why we are currently not going that way. If it’s because we now have the MHR, that will become the worst thing about the MHR project in time.

But we don’t know what the ADHA position is yet. The ADHA interoperability consultation is just beginning, after all. But you have to suspect the agency understands the dynamics here in the end.

As a part of ongoing work the ADHA has been doing on sorting out how secure messages can be transferred from one provider to another, and to service providers, one pilot project has used FHIR at the GP end and the provider end. And apparently its working a treat! Why do that if you weren’t considering the ultimate utility of FHIR?

There is a long way to go on this journey. But the good news is that, although it still looks a divided and messy path, it probably isn’t. Water and enabling technology tend to flow downhill, where ever they are.

Which brings us to possibly most important point of interoperability which Grieve preaches wherever he goes, and which feels entirely intuitive.

Although Grieve’s everyday work is FHIR and how it can be applied, he is at pains to explain that success in interoperability is not about technology, it’s about people and culture.

I’ll leave you with this short explanation directly from Grieve’s presentation to the ADHA event.

“People use the word ‘technology’ a lot in respect to solving the issues we face around interoperability. But it’s not a technology problem. It’s an information management problem.

“Technology comes and goes. Information management is where the hard stuff is. A lot of people misunderstand what FHIR is – yes, it’s got technology in it, but it’s not about technology.

“FHIR is two things – a community of people, and a set of technical agreements about information management.

“The really valuable thing FHIR has is people and the culture that it helps people build. It’s a culture of sharing and openness and it’s starting to transform healthcare IT around the world.”