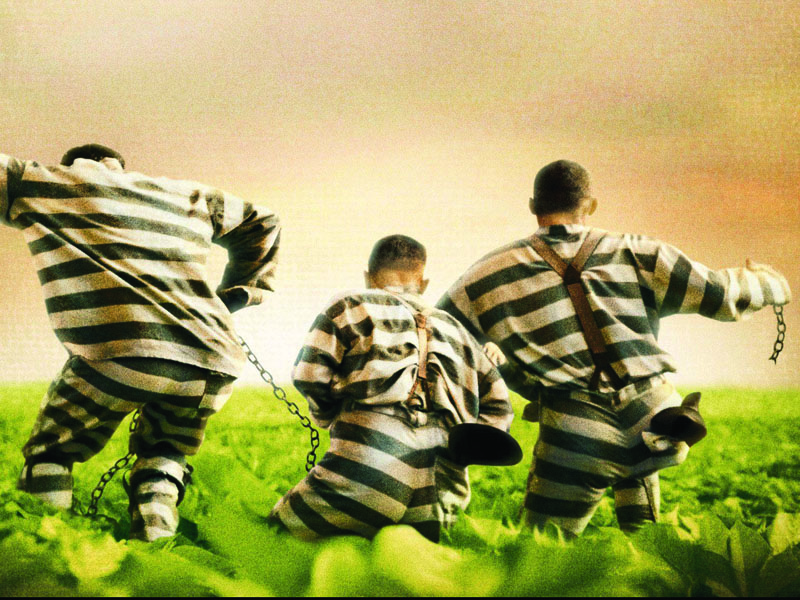

What GPs need to know about the identification, assessment and management of the post-custodial patient

What GPs need to know about the identification, assessment and management of the post-custodial patient

The number of adults incarcerated in Australia has been steadily rising over the last 10 years. The absolute number in the March 2016 quarter was 37,996, with an incidence of 205 per 100,000 population.

The rates are even higher when specific groups are analysed, with an Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander [ATSI] rate of 2338 per 100,000. In Western Australia, the ATSI rate in the March 2016 quarter was 3004 per 100,000. These figures relate to the whole adult population, so the incidence rate for male persons between the ages of 18 and 40 would necessarily be even higher.

Keeping in mind that these figures are just the spot incidence, the incidence rate in a person’s lifetime for having ever been in custody is several times higher. These incidence rates mean that almost all Australian GPs are seeing post-custodial patients regularly, whether they realise it or not.1

Australian prisons follow international norms in that they have a system of providing healthcare to inmates which is intended to be free of charge, and to be at least commensurate with that provided to patients in the community.2

Historically, responsibility and funding for prisoner healthcare in Australia has been the responsibility of each State and Territory government, with prisoners excluded from the federally-funded Medicare/PBS system, and excluded by logistics from the private health insurance system. The state government-funded, hospital-based emergency and outpatient systems have provided a full suite of care, albeit with variable waiting times.

Today, many non-emergency health services are no longer provided by state-funded health systems, and these have been cost-shifted back on to federal health care infrastructure. The increasingly limited funding makes it challenging for prison health services to achieve the goal of commensurate care.

Another limiting factor on prisoner health care is that the safe and timely transport of prisoners to outside ppointments is at times an insurmountable logistical challenge.3

Being aware of the post-custodial status of a patient can be a useful clinical indicator for a treating GP, however this is likely to be a sensitive issue which needs to be handled carefully and confidentially. Also, many innocent patients have been held for long periods on remand in Australian jails.4 Another significant, but difficult to quantify, proportion of convicted prisoners are innocent, and have been wrongfully convicted.5

The healthcare provided in custody, no matter how good it may have been at the time, presents what could be termed “the custodial health paradox.” Most physical health parameters improve for most individuals while in custody; but having been in custody in itself is a significant predictor for life-long disadvantage with associated impaired health outcomes. This is a clear reminder that the key determinants for good health relate to long-term socioeconomic and mental health factors, rather than short-term access to medical treatments.

Individuals who have spent time in custody, particularly at a young age or for longer than six months, will have reduced access to jobs, education, accommodation and supportive social networks, and will be more likely to suffer from mental illness. Any short-term health benefits achieved in custody are more than outweighed by the long-term disadvantage posed by the disruption of the individual’s social networks.

Health implications

It is useful for doctors to be aware of a patient’s post-custodial status, as this is associated with various effects and health issues which may need to be addressed.

These effects, both positive and negative, can be physical, psychological and social. Positive health effects of custody can be evident in a previously unstable patient with known complex health and social problems, who presents looking unusually and unexpectedly well. This improvement may be due to the patient having been in successful residential rehabilitation, or they may have been in custody. In these environments, the patient has had access to food, shelter, reduction of access to drugs and alcohol and access to regular free medication. The short-term benefit for some patients can be marked, and occasionally can be long-lasting, particularly after custodial sentences of less than 12 months.

The potential negative effects of custody are many and interlinked. Physical issues include increased risks associated with weight gain due to prison diet and lack of exercise. Weight gain can also be exacerbated by appetite-stimulating medications, such as mirtazapine and quetiapine.6

While in custody, substance-use patterns can change to higher-risk behaviours and riskier drugs, and there can be normalisation of needle-sharing, with the associated blood-borne virus transmission risk. In Australian jails, unlike a number of other developed countries, access to clean-needle programs and to opiate-substitution therapies are not managed in a way commensurate with community standards. In the remaining Australian jurisdictions where smoking has not yet been banned, many patients either start smoking or smoke more heavily.

Detrimental psychological issues relating to custody include the development of post-traumatic stress disorder secondary to traumatic experiences in custody. The institutionalisation which occurs in custodial environments tends to ingrain the psychological problem of a pathologically external locus of control. Incarceration also ingrains a loss of ownership of societal rules, resulting in worsening disenfranchisement.

These two phenomena tend to result in behaviours that can earn a patient the psychiatric label of “antisocial personality disorder.” Another psychological phenomenon demonstrated in ex-prisoners relates to difficulties assimilating a new identity – that of an ex-con.

This engenders a grief reaction in response to the loss of the former self and the former life.

Some mental-health patients who would have been on compulsory treatment regimes in the community remain untreated in custody. This is partly due the higher threshold for compulsory treatment in custodial settings. This is often the result of the ethical and legal issues that restrict the use of compulsory injections in custody, and partly due to the logistic difficulty of transferring prisoners into the insufficient number of approved hospital beds, where preference is given to civilian patients. Some patients who have been found by the courts to be not guilty due to mental illness are still held in mainstream jails in Australia because more appropriate options aren’t available.

Negative social effects of incarceration relate to loss of social and employment continuity and supports, which is amplified if sentences are longer than six months. The ex-prisoner is also inducted into an “outside-the-law” social set. These negative effects are particularly marked for post-custodial women, who have shockingly high health risks, especially in the areas of domestic violence and suicide.

These effects can be intergenerational, both up and down the family tree, with negative effects on children and elderly parents, whose lives and support systems were interrupted when their carer received a custodial sentence.

Identifying the post-custodial patient

Occasionally a post-custodial patient will self-identify, but this is unusual. Aspects of history and examination that may indicate previous custodial time include the following factors:

• The use of specific custodial vocabulary

• Tattoo style and pattern

• The patient’s attitudes to violence and assault

• Their substance use pattern and BBV status

• Their medication regime

• The site and type of their accommodation

Prison language

• Calling all female doctors and nurses “Miss”

• Calling male doctors and nurses “Medic”

• Vocabulary such as “Boss”, “Guv,” “Shiv,” “Super[intendant],” “Grats,” “Spends,” “Down the back,” “Lock-down,” “Gate fever”

Tattoos

Poor quality blue-ink tattoos are now uncommon, except in custodial patients. Professional tattoos are now cheaper and more easily accessed. Tattoos at a corner of an eye are almost universally custodially-acquired, often these are teardrops or other symbols. Altered or removed tattoos may indicate forensic issues in the past.

Attitudes to violence

A common attribute of post-custodial patients is an acquired nonchalance regarding assault and violence. If a patient presents with assaultive trauma and expresses no wish or expectation of involving police or other authorities, this may indicate that the patient has the “victim-desensitisation phenomenon”, where violence has been a routine part of life for so long it is no longer a concern. Such nonchalance may also indicate a personality trait of bravado and lack of empathy.

Previous custodial experience predisposes to both of these factors. In custody, violent incidents are not always referred to the police, but are dealt with internally either by the prisoners themselves or by immediate action by the custodial officers, or by the prison superintendent, or by a visiting magistrate who imposes internal disciplinary measures. This occurs outside of the usual civilian legal system. It is rare for matters to be referred to the police.

Substance use

In the context of internationally-enlightened policies in Australia, needle-sharing has become less prevalent due to the relatively easy access to clean injecting equipment, except in prisons. Nonchalance about needle-sharing may indicate custodial experience. The use of intravenous buprenorphine or the injecting of distillates of opiate patches is often a custodially-triggered behaviour. Buprenorphine is not tested routinely on jail urine screens, and the film forms are easy to traffic. Blood-borne virus infections, especially hepatitis C, may justify a discrete enquiry about possible custodial experience.

Medications

Unusual patient expectations and presentations regarding medications may be due to previous custody. The custodial pharmacopoeia is smaller and different to the mainstream one. It is generally more restricted and “old-fashioned” (sometimes this can be an evidence-based and cost-effective advantage).7 Many, and in some locations all, medications are not permitted to be held on person by prisoners, and the logistics of administering medications to patients mean that daily doses are generally preferred, even if they are not clinically optimal.

Any medication with tradeable potential is minimised in custody, including not only obvious agents such as opiates (including Tramadol) or benzodiazepines, but also less commonly abused medications such as sedating antihistamines, anti-epileptics (especially pregabalin) and antipsychotics (especially quetiapine). Diabetes management involves a higher threshold for injection therapy (due to needle safety and timing issues), so recent time in custody may be the reason a patient is on a once- or twice-daily mixture insulin rather than a more effective four times a day basal/bolus regime.

Custodial patients tend to be prescribed, and to remain on, antipsychotic medications for the non-PBS indications of drug-induced psychosis or personality disorder, and they may have unrealistic expectations of receiving these medications in the community subsidised under the PBS. Post-custodial patients who have been receiving most S2 and S3 medications for free in custody may be surprised that their medications are now over-the-counter rather than on PBS-subsidised scripts.

Accommodation

Certain locations are preferred and frequently used by prison resettlement agencies. Get to know them in your area. If a patient reports issues of extremely limited contact with their children, this may also indicate significant forensic issues.

Consult strategies

• Identify that the patient has been in custody. This may not be divulged initially and may be a sensitive issue

• Establish the patient’s primary agenda early (or it may be inconveniently revealed at the very end of the consultation). You should acknowledge it, even if unable to fulfil it

• Identify other relevant issues by asking open-ended questions (informed by your new awareness of the issues)

• Express empathy as to how challenging it must have been. The ramifications are too complex to deal with completely in one consultation, and certainly complex enough to initiate a care plan if considered appropriate

• Obtain written consent to obtain a discharge summary from the prison system and other relevant agencies (e.g. previous residential rehab). These summaries vary in quality and quantity, but can be very useful and at times comprehensive, depending on the jurisdiction from which they emanate

GP Saftey

One serious issue in consultations with a post-custodial patient can relate to unrealistic and impractical expectations of the patient as to medications a GP is able to prescribe. Here are some things you can say to defuse and deflect responsibility for saying no in such situations, while maintaining rapport that has been developed initially:

• A GP has a professional requirement to follow Medicare and PBS regulations

• A GP has an ethical obligation to RACGP/Medical Board of Australia to practise “evidence-based medicine”

• A GP is medicolegally unable to prescribe “off-label”

• A GP has to comply with an external safety requirement to confirm information with previous prescriber/pharmacy prior to re-issuing a prescription

• Current guidelines on best practice do not, or no longer, support the prescribing of that medication for that indication

If a GP is overtly threatened by a patient, it is acknowledged by professional bodies that a clinician may be forced to say yes to the patient’s demands, but then must promptly report this to the relevant bodies.

Dr John Hardy, MB BS, FRACGP, was the GP at Acacia Prison in WA from 2008 to 2015 and was a former chair of the RACGP Custodial Health Specific Interests Group. He is now working at a remote AMS in northern Australia

References:

1: http://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/mf/4517.0

2: https://www.penalreform.org/resource/standard-minimum-rules-treatment-prisoners-smr/

3 http://www.racgp.org.au/your-practice/standards/standardsprisons

4 http://www.aihw.gov.au/publication-detail/?id=60129543948

5[https://www.google.com.au/search?sourceid=navclient&aq=&oq=wrongful+conviction+rates+Australia

6 https://www.mja.com.au/journal/2013/199/4/

7 http://www.rpharms.com/pressreleases/pr_show.p?id=356