Dr Corey Smith and Dr Shiva Roy outline the latest thinking on the diagnosis and treatment of atrial fibrillation

Atrial fibrillation is the most common cardiac arrhythmia seen in clinical practice, with up to 10% of the population experiencing an episode by the age of 80.1 AF causes symptoms such as palpitations, dyspnoea and fatigue, and recurrent hospital admissions and medical treatments. Indirectly, AF is a major cause of stroke.

AF occurs more frequently in elderly patients with pre-existing heart problems, such as hypertension, congestive cardiac failure and valvular heart disease, but can also present in younger patients with structurally normal hearts.

There are five key points to the management of AF:

1. Assessment of haemodynamic stability and acute rate control

2. Management of precipitating factors

3. Assessment of stroke risk and appropriate anticoagulation

4. Optimisation of rate control or maintenance of sinus rhythm

5. Management of lifestyle factors and comorbidities, and ensuring medication adherence

Initial investigations

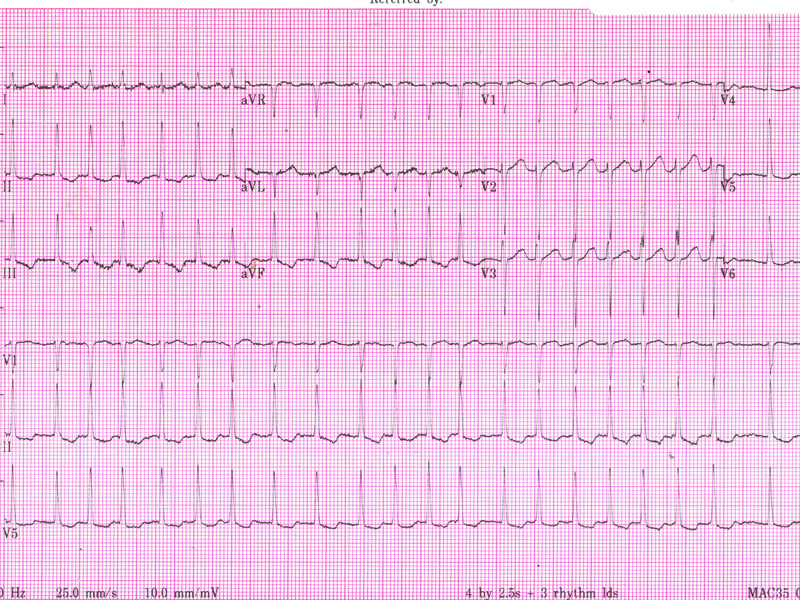

All that is needed to confirm a diagnosis of AF is an ECG demonstrating an irregular narrow complex rhythm without discrete P-waves. Occasionally in paroxysmal cases, longer-term monitoring may be required to catch an episode of the arrhythmia.

When measuring blood pressure, automated sphygmomanometers are often inaccurate when a patient is in AF, and a manual blood pressure reading should be taken.

Additional investigations for a new diagnosis, recurrence of AF, or tachycardic episode in a patient with chronic rate-controlled AF, should be targeted to the clinical situation to determine whether there is a treatable precipitant.

This may include screening for infection, particularly pneumonia or occult urinary infection, hyperthyroidism and electrolyte disturbance.

Blood work to check renal and hepatic function is necessary to inform the choice of therapy, as newer oral anticoagulants and many anti-arrhythmic drugs are excreted renally, and may be contraindicated, or used with caution and dose-adjusted in patients with renal impairment.

All patients with a new presentation of AF should undergo a transthoracic echocardiogram.

This offers valuable information as to the presence of underlying cardiac structural abnormalities that may be clinically occult. Echocardiographic assessment includes checking for ventricular function, valvular heart disease and measurement of atrial size. Progressive enlargement of the atria occurs with longer duration of AF and reduces the chance of successful maintenance of sinus rhythm.

Case study

An 86-year-old woman presents with one week’s history of fatigue, decreased exercise tolerance and several pre-syncopal episodes. She denies fever or focal infective symptoms and has no palpitations or chest pain. She has a history of hypertension, but no prior cardiac or respiratory disease.

On examination, she appears well. Pulse is rapid and irregular 150 bpm. Blood pressure is unrecordable with an automated sphygmomanometer.

No murmur is audible, and there are no signs of cardiac failure. An ECG is obtained.

Her ECG demonstrates an irregular narrow complex rhythm without discrete P-waves, confirming AF with a rapid ventricular rate of approximately 150 bpm. There is inferior T wave inversion, which may indicate ischaemia or may simply reflect the rate-related changes.

Management

Patients with a very rapid ventricular rate, severe symptoms or signs of decompensated heart failure should usually be admitted to hospital for immediate management. Patients with stable haemodynamic signs and mild symptoms can often be managed in an outpatient setting.

Many new cases of AF are paroxysmal and will self-terminate within 48 hours. Episodes lasting longer than 48 hours will often require chemical or electrical cardioversion to terminate the arrhythmia.

Rate versus rhythm control

Almost all patients should receive an agent to slow the ventricular rate initially, to ameliorate symptoms. A beta blocker (metoprolol, atenolol), nondihydropyridine, calcium channel blocker (verapamil, diltiazem) or digoxin may be the agent of choice. Following this initial management, a decision regarding the rhythm control strategy can be made.

Studies have shown an improvement in exercise tolerance and quality of life if sinus rhythm can be achieved for a clinically meaningful duration and without burdensome medication side effects. Rhythm control is generally preferred for younger symptomatic patients, however evidence of an improvement of mortality benefit is lacking .2

The choice between the anti-arrhythmic drug options is based on contraindications to the medications and the consideration of medication-specific side effects. As all antiarrhythmic drugs have the potential to act as a proarrhythmic, they must be used with some caution, particularly if there is coexisting structural cardiac disease. In Australia, the main options are sotalol, amiodarone and flecainide.

Electrical cardioversion under sedation is performed as a day procedure to achieve sinus rhythm in anticoagulated patients. Trans-oesophogeal echocardiography is often performed prior to cardioversion, in order to visualise the left atrium and atrial appendage, and to exclude thrombus formation, which is a contraindication to cardioversion.

Stroke Risk and Anticoagulation

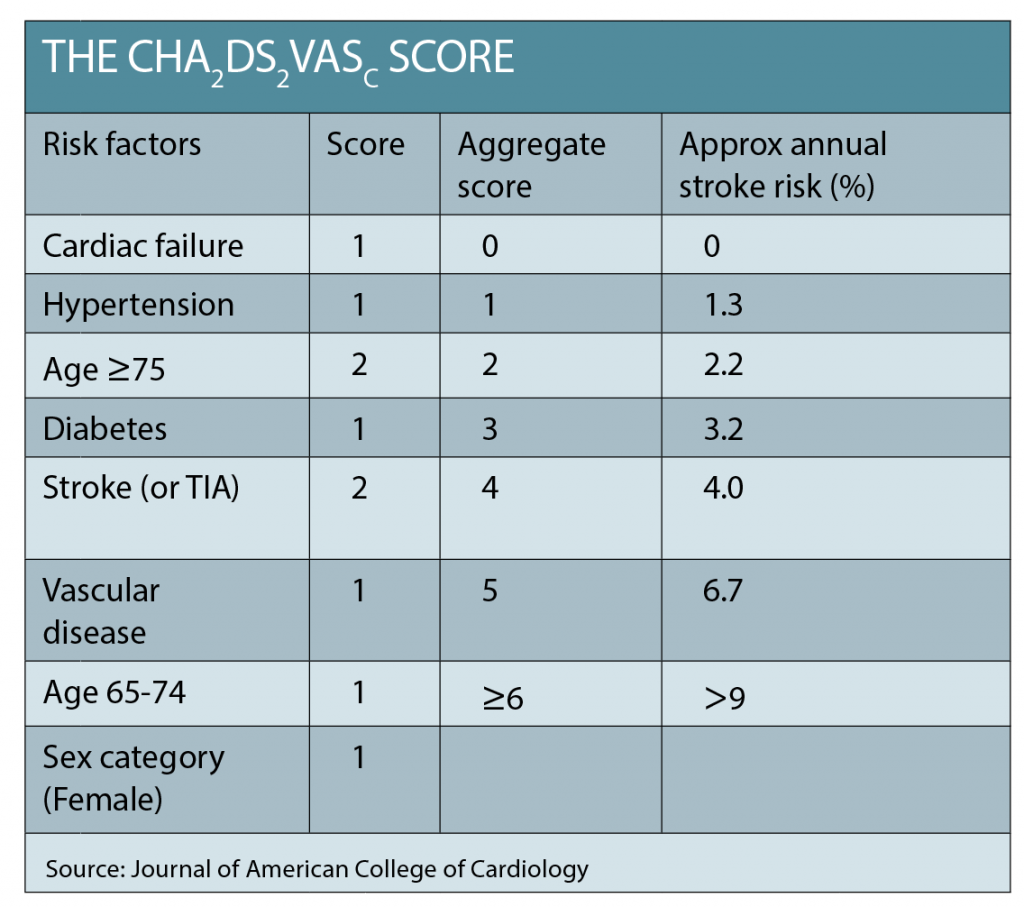

The CHADS2 or CHADS2¬VASc scores are used to quickly assess a patient’s risk of thromboembolic complications from AF, with a score >1 a strong indication for anticoagulation (See table below).

The numerical result of the CHADS2¬VASc approximates the percentage risk per year of stroke. An assessment of any contraindications and the relative risk of bleeding from anticoagulation should also be undertaken. Treatment with an anticoagulant has strong evidence of net benefit, yet is consistently demonstrated to be underutilised in AF patients. Despite concerns about falls or bleeding, frail and elderly patients derive a greater benefit from anticoagulation because of their very high risk of stroke.3 Anticoagulation should be initiated promptly.

Both the novel oral anticoagulants (NOACs – Factor Xa inhibitors: rivaroxaban and apixaban, and the thrombin inhibitor dabigatran), as well as warfarin, have strong evidence for stroke prevention in AF, and are all superior to aspirin. In patients with moderate to severe renal disease, rheumatic heart disease or mechanical heart valves, warfarin is indicated. In the absence of these conditions, NOACs have rapid onset of effect, may be easier to use and have a higher patient acceptance.

Back to our case…

Our patient has a very rapid heart rate, but no signs of heart failure. She is referred by her GP to the heart clinic. Her CHADS2VASc=4.

At the heart clinic, she is given 50mg of oral metoprolol, started on a NOAC for anticoagulation, and admitted for continuous ECG monitoring. ECG shows normal left ventricular systolic function and no valvular heart disease. Despite the addition of digoxin, her ventricular rate remains difficult to control.

A transoesophageal echocardiogram is performed. It excludes thrombus in the left atrium.

Electrical cardioversion is successful in returning her to sinus rhythm. She is now symptomatically much improved and is discharged the following morning on anticoagulation and beta-blockers. She is instructed to follow up with her GP the following week, and to see her cardiologist in a month.

Following an episode of AF, heart rate and ECG will help to assess the effectiveness of rate control and to ensure that the patient has maintained sinus rhythm. Other issues to address include medication side effects and compliance, as controlled trials indicate that patient persistence with anticoagulation can be poor.

The follow-up appointment is also a good time to screen for potential comorbidities, including hypertension, diabetes, obstructive sleep apnoea, as intervention to optimise treatment of these conditions can reduce the burden of AF.

Lifestyle and modifiable risk factors

Recent research has focused on the role lifestyle factors play in AF occurrence, and there is now strong evidence to support follow-up interventions to treat modifiable risk factors, as these can have a big impact on long-term success in controlling AF.4

Obstructive sleep apnoea

Patients with obstructive sleep apnoea have an increased risk of developing AF and are more likely to experience AF recurrence or treatment failure. History-based screening questionnaires may be utilised, and patients can be referred for diagnostic sleep studies and treatment. Treatment of obstructive sleep apnoea with CPAP or other measures reduces the rate of AF recurrence .5

Alcohol intake

Excessive alcohol intake is a strong modifiable risk factor for AF. Paroxysmal AF can be induced during or after acute alcohol consumption or following an episode of binge drinking. Additionally, even moderate daily alcohol consumption increases the risk of AF in a dose-dependent fashion.6

Exercise

Paradoxically, highly trained individuals and endurance athletes, such as marathon runners and triathletes, are at a significantly higher risk of AF. However, regular moderate physical activity reduces the chance of AF recurrence. Patients can be advised to return to their usual exercise without restrictions, and sedentary individuals should be encouraged to regularly engage in moderate intensity physical activity.7

Weight loss

Recent Australian research8 demonstrated that sustained weight loss improved outcomes for AF with or without antiarrhythmic drugs, and reduced the burden of symptomatic AF. In overweight patients (BMI >27) a modest weight loss of 3-9% body weight was beneficial, and further benefit was achieved with weight loss >10%. Weight loss should be supported in the management of AF, along with other management strategies.9

Advanced treatments

Some patients remain symptomatic and have frequent recurrences of AF despite antiarrhythmic drug treatment, while others cannot tolerate the side effects and cease therapy. This group may be candidates for catheter-based ablation therapies for AF. These procedures have gained popularity over the last 10 years, and there is now considerable experience in the field.

Pulmonary vein isolation is the most commonly performed procedure. It can be highly successful in eliminating AF in selected patients with paroxysmal AF. This is performed under deep sedation or general anaesthesia via catheters placed in the heart through the femoral vein. The procedure usually requires an overnight stay and carries an approximately 1-2% risk of procedural complications. Repeat procedures may be required for control of AF, and evidence is currently lacking regarding safety of discontinuation of anticoagulation following a successful procedure.

Elderly patients with permanent AF and difficult- to-control ventricular rates, intolerance of antiarrhythmic drugs, or who alternate between symptomatic tachycardia and bradycardia, may be a candidate for AV node ablation and pacemaker insertion. This induces complete heart block and eliminates the problem of AF-induced tachycardia. Anticoagulation is still required to reduce the risk of stroke.

Dr Corey Smith is cardiology registrar at Sutherland Hospital. Dr Shiva Roy is senior staff specialist in cardiology, Sutherland Hospital

References:

1. Go AS, Hylek EM, Phillips KA, et al. Prevalence of diagnosed atrial fibrillation in adults: national implications for rhythm management and stroke prevention: the Anticoagulation and Risk Factors in Atrial Fibrillation (ATRIA) Study. JAMA. 2001;285:2370–5

2. Steven N. Singh, X. Charlene Tang, et al. Quality of Life and Exercise Performance in Patients in Sinus Rhythm Versus Persistent Atrial Fibrillation: A Veterans Affairs Cooperative Studies Program Substudy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;48(4):721-730.doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2006.03.051.

4. Kirchhof P, Benussi S, Kotecha D et al. 2016 ESC Guidelines for the management of atrial fibrillation developed in collaboration with EACTS. European Heart Journal Oct 2016, 37 (38) 2893-2962. DOI:10.1093/eurheartj/ehw210

5. Celine Gallagher, Jeroen M. L. Hendriks, Rajiv Mahajan, Melissa E. Middeldorp, Adrian D. Elliott, Rajeev K. Pathak, Prashanthan Sanders & Dennis H. Lau (2016): Lifestyle management to prevent and treat atrial fibrillation, Expert Review of Cardiovascular Therapy, DOI: 10.1080/14779072.2016.1179581

6. Shukla A, Aizer A, Holmes D, et al. Effect of Obstructive Sleep Apnoea Treatment on Atrial Fibrillation Recurrence: A Meta-Analysis. JACCCEP. 2015;1(1):41-51. doi:10.1016/j.jacep.2015.02.014.

7. Larsson S, Drca N, Wolk A. Alcohol consumption and Risk of Atrial Fibrillaton: A prospective study and dose-response meta-analysis. J Am CollCardiol. 2014;64(3);281-289. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2014.03.048

8. Elliott A, Mahajan R, Pathak R, et al. Exercise Training and Atrial Fbrillation: Further Evidence of the Importance of Lifestyle change. Circulation. 2016;133:457-459. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.115.020800

9. Pathak RK, Middeldorp ME, Meredith M, et al. Long-Term Effect of Goal-Directed Weight Management in an Atrial Fibrillation Cohort: A Long-Term Follow-Up Study (LEGACY). J Am CollCardiol. 2015;65(20):2159-2169. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2015.03.002