GPs play a crucial role in helping patients with wet AMD stick to their long-term treatment

Since 2007, neovascular age-related macular degeneration (wet AMD) has been highly treatable with PBS-listed anti-vascular endothelial growth factor (anti-VEGF) agents.

But patients with wet AMD have to keep going back to their ophthalmologist every few months for the rest of their lives to get these intravitreal injections. Missing these injections risks blindness, even if symptoms have disappeared.

You’d think that the fear of going blind would be enough to persuade patients with wet AMD to adhere to treatment.

Older patients who lose their vision to AMD are looking at a bleak future where they can’t drive, shop or read and may end up at an aged care facility much earlier than they expected.

But for some patients, the cost of visiting a specialist five to eight times a year is too high. And for some patients living in rural and remote areas, it just takes too long to travel to see an ophthalmologist.

The average age of initiating therapy for wet AMD is 80 years. Sometimes major life events, such as hip surgery or moving into a nursing home, disrupt patients’ schedules and they fall out of the habit of seeing their ophthalmologist.

This is where GPs can really make a difference, says Professor Paul Mitchell, a clinical ophthalmologist at Westmead Clinical School at The University of Sydney.

“People do get a bit of fatigue with having the injections over time, a little bit fed up,” he says.

“But GPs can keep reassuring them that this is critical to keep their vision at the level it is. They do need to keep coming back.

“It’s making sure the GP reminds people. ‘Hang on, have you had your eye injection? Have you missed those appointments? Make sure you get back to your specialist and get it done’.”

Intravitreal injections sound excruciating, but actually the procedure is relatively painless and quick, says Professor Mitchell.

“The treatment involves injecting the drug, either Lucentis or Eylea, into the eye through the sclera, about 4mm back from the cornea. We give an antiseptic first and local anaesthetic drops. And really, that’s enough for most people to stop any pain or discomfort.

“It’s a very fast injection and you can distract people: Bang! ‘Oh, have you done already doctor? I didn’t feel anything.’ And it’s quite amazing sometimes a relative will be watching and say, ‘I can’t believe she didn’t feel it’. But you know, it’s actually not a particularly sensitive area where we put the injections, and we get good at doing this without causing much discomfort. And obviously, we don’t want to cause much discomfort because that would stop people coming back.”

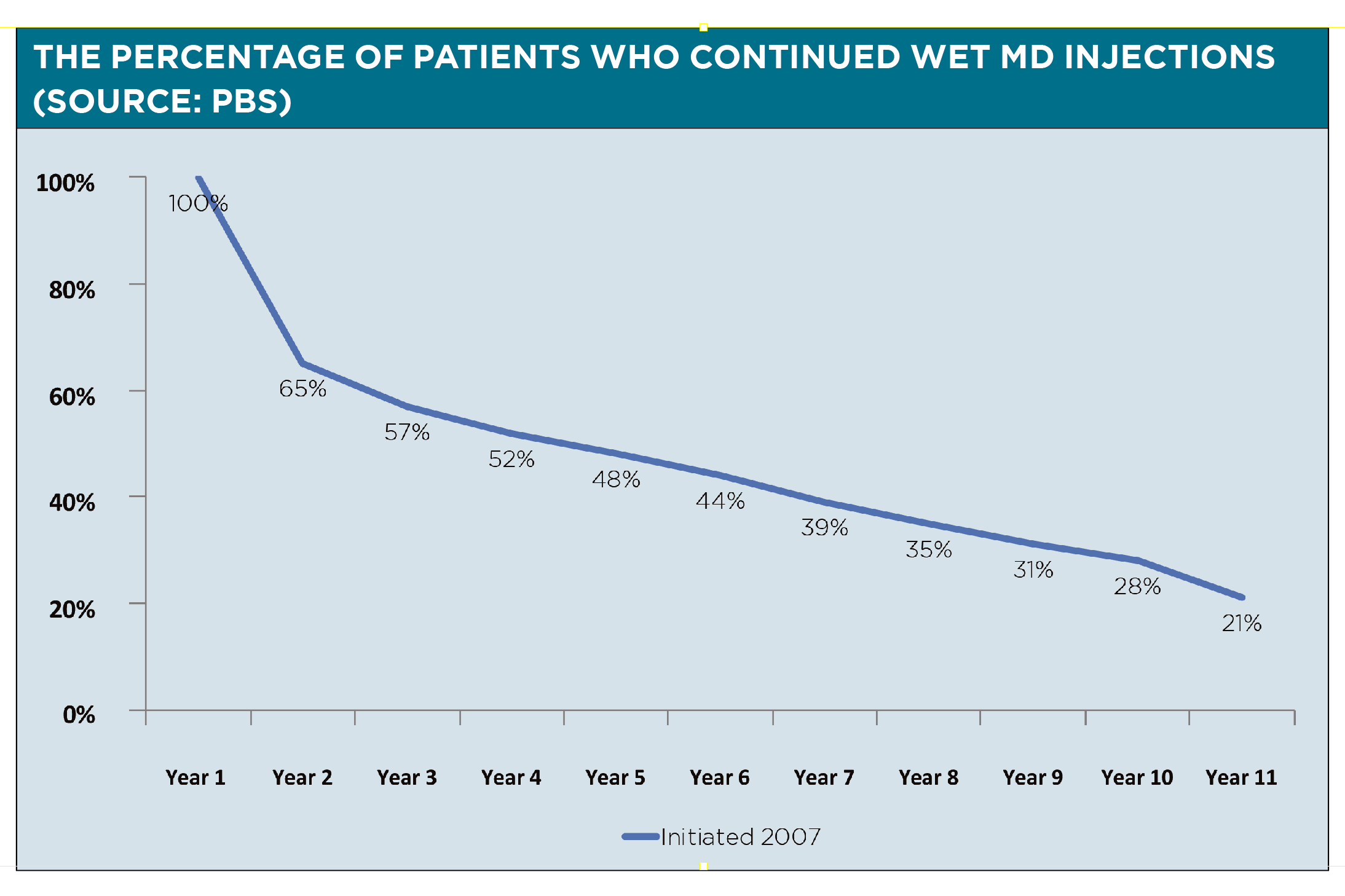

Unfortunately, PBS data from 2016 show that around 41% of patients with wet AMD dropped out by the end of the first year of treatment.

“And that is really terrible,” says Professor Mitchell. “Much of the reason for people dropping out is that maybe they just haven’t been educated well enough about how important this is. “There are the tyranny of distance issues. There’s the burden of therapy. There are also out of pocket costs and we know that that’s actually a major problem.”

Professor Mitchell bulk bills all of his clients. Not all ophthalmologists can afford to do that, but they will generally make accommodations if a GP calls them to let them know that a patient has dropped out of treatment for AMD due to cost, says Professor Mitchell.

Public hospitals don’t offer anti-VEGF treatment in NSW but there are clinics that bulk bill dotted around the state.

Dee Hopkins, the CEO at the Macular Disease Foundation Australia, says that GPs are welcome to call their National Helpline (1800 111 709) to get assistance on how to find affordable and accessible AMD treatment for patients.

“We often take calls … and most of the time actually the ophthalmologist will say, ‘Look, let’s work out something that the patient can afford’,” she says. “But it’s not always about the affordability. It is sometimes an access point issue, particularly for people in rural areas who may not have access to …. ophthalmologists. So, again, we can help people and link them in.”

Ms Hopkins says she was motivated to accept the position of CEO last year because her father had neovascular AMD.

“Unfortunately, this was before the anti-VEGF drugs,” she says. “He was basically legally blind. So, I’d have a 50% risk myself.”

Macular degeneration is the leading cause of severe vision loss and blindness in Australia. Around 15% of Australians over 80 experience vision loss or blindness from AMD, and one in seven over 50 are in early stages of the disease.

There are two types of late-stage AMD:

atrophic (dry) AMD is caused by the gradual loss of retinal cells, which affects central vision.

neovascular (wet) AMD, which occurs when fragile blood vessels form and leak fluid under the retina, leading to a rapid loss of central vision.

The wet variety is less common and affects 10% of AMD patients.

There is currently no treatment available for dry AMD, but there are two PBS-listed drugs for wet MD: ranibizumab (Lucentis) and aflibercept (Eylea).

In 2017 around 51,000 Australians started treatment for wet AMD, with around 11,500 being new patients.

The pivotal MARINA study, an RCT involving around 700 patients with wet AMD in the US, found that ranibizumab injections prevented severe vision loss in the majority of patients over two years.

Without the injections, around three quarters of patients with wet AMD would be blind within about two years, says Professor Mitchell.

In the earlier stages of AMD, there may be no noticeable signs.

“What GPs can do is identify the classic risk factors in patients,” says Ms Hopkins. “So, the over 50s, the smokers, the people with diabetes, those with a family history – all of those people are inherently at risk.”

Patients who are at high risk of AMD can get regular comprehensive eye exams done at their optometrist to help with early detection of the disease.

Everyone over 50 can keep an eye out for early signs of AMD by using an Amsler grid to check for distortions in vision.

The Macular Disease Foundation Australia supplies free Amsler grids fridge magnets to GPs and patients online.

Any sudden changes in vision in older patients should be treated as an emergency, says Professor Mitchell.

If patients over 50 start to see dark patches or a kink in the centre of vision or find they have difficulty reading they should be referred to an ophthalmologist immediately, he says.

“They don’t have to present that day, but that week or the next week,” he says. “Because the better the vision we can start the treatment at, the better vision we will maintain.”