Among the hundreds of apps for patients with chronic rheumatic conditions, only a few have a tick of approval from rheumatologists

“Arthritis? But that’s not possible! I’m too young.”

Carly, a 33-year old from the Yarra Valley in Victoria, couldn’t believe she had rheumatoid arthritis (RA) at first: “I have to keep saying it in my head because it doesn’t seem real.”

Six months after her diagnosis, she wasn’t feeling much better. Just trying to feed her toddler sapped all her energy: “I’ve tried loads of things, but I’m still so exhausted! I’m trying to stay positive. What is this going to mean for my career? My family?“ She was angry too: “Why me? I just want to be normal again.”

Carly’s rheumatologist assured her that there were a range of biologic medicines; they just needed to find the right one. It took almost three years for Carly to get her RA under control.

There were moments of despair but, slowly and steadily, things improved. Carly went to a therapist for her depression. She joined a patient support group. She discovered that swimming was the right kind of exercise for her. ”Not every day is amazing, not every day is terrible. There’s just so much more to my life than my RA,” Carly said.

This real story of one patient’s journey is now being used to help thousands of patients around Australia better understand their condition.

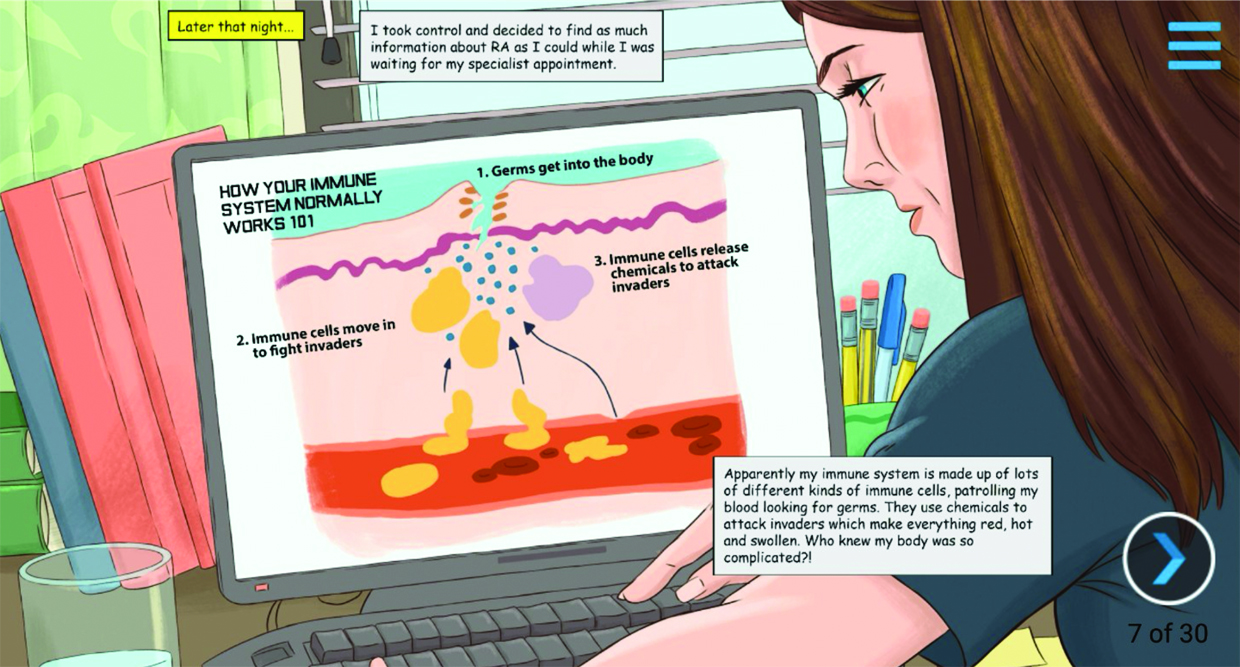

Australian company Medicine X has presented Carly’s story as a graphic novel inside a smartphone app called Rheumatoid Arthritis Xplained.

“Rheumatologists often don’t have a lot of time to sit down with patients and explain their conditions in detail and answer all their questions,” Cathryn Corcoran, the managing director of Medicine X, tells The Medical Republic.

The digital comic book translates “doctor speak” into everyday language that anyone can understand regardless of age or health literacy.

A team of rheumatologists write and review the stories, and then graphic novelists in the US transform thetories into eye-catching cartoons. The app is sponsored by Pfizer, which reviews the content for clinical accuracy.

Around 11,000 patients in Australia have read the story, and more than 3,000 in New Zealand.

Medicine X has also spun their app into a closed Facebook community with 2,400 members. This community is often invited to ask questions about their condition, which Medicine X representatives then put to rheumatologists at medical conferences.

“RA is one of our most active groups,” says Ms Corcoran. “It’s because it’s a chronic condition that people deal with every day. They are an amazing group that we can approach and ask to be part of a focus group.”

Associate Professor Paul Bird, a rheumatologist at UNSW who helped edit the RA Xplained story, regularly recommends the app to his patients.

Finding out that you have RA and being given a wordy, confusing fact sheet by your doctor can be a distressing experience, he says.

“[RA Xplained] appeals because it is visual,” he says. “It’s also about someone they can identify with – a young woman who has small children.

“For people who have been diagnosed and they are thinking, ‘What does this all mean?’ It’s an entry point for their learning.”

Associate Professor Maureen Rischmueller, a rheumatologist from Adelaide who also lent a hand editing RA Xplained, says the app gives patients reassurance that they are not alone.

Post-partum onset of RA is common, but there is not a great deal of information about that experience, she says.

“It’s a very difficult time, obviously, having a new baby … and this new diagnosis is such a huge shock to many people,” says Associate Professor Rischmueller. “The app conveys what people might be going through at that stage.”

Medicine X is now in the process of writing graphic novels to explain psoriatic arthritis and ankylosing spondylitis.

There are almost 1,000 apps for managing arthritis currently available, but RA Xplained is one of only a select few that are being actively promoted by clinicians.

Associate Professor Rischmueller says she’s holding back on recommending other smartphone apps. “I guess I’m waiting for other people’s evaluations of them rather than sending people down tracks when I haven’t explored them myself.”

Most of the apps for arthritis are too detailed, or costly, says Associate Professor Bird. The only other app that he routinely recommends is the FODMAP app for patients who are interested in this diet.

Over the Tasman Sea, rheumatologist Dr Rebecca Grainger, at the University of Otago in Wellington, has conducted a systematic review of apps for the assessment of rheumatoid arthritis disease activity in iTunes and Google Play app stores, and she has found a lack of high-quality products.

Out of 19 relevant apps included in the study, ArthritisPower was the only app that met international standards for the calculation of composite disease activity and tracking of patient data.

ArthritisPower was launched last year by US patient advocate group CreakyJoints in partnership with the University of Alabama. It has been downloaded nearly 16,000 times. The free smartphone app is targeted at patients with all types of rheumatic conditions. It is a symptom tracker that donates health data to a research registry.

“People with arthritis simply open the app and then select which disease assessment measures they want to track over time, such as measures for pain, sleep, or mobility,” Dr Ben Nowell (PhD), the director of research of the Global Healthy Living Foundation (the umbrella organisation that founded CreakyJoints), tells The Medical Republic.

“It encourages the patient to proactively participate in their treatment,” he says. “It’s another way for a patient to feel ‘heard’ by the doctor.”

The app brings information that would normally be “fuzzy” into clearer focus by overcoming issues such as recall bias, says Dr Nowell. A person living with RA, for example, may not remember exactly when a flare started or ended or even how bad it was, he says.

The app acts like a time capsule, helping doctors to observe how treatment is affecting sometimes unpredictable autoimmune or musculoskeletal disease activity.

The data collected through the app is analysed by researchers, and the findings are presented at meetings of the American College of Rheumatology and the Annual European Congress of Rheumatology.

CreakyJoints was founded about 20 years ago by Seth Ginsberg, who was diagnosed with spondyloarthropathy at age 13. The organisation is dedicated to providing arthritis education, support, advocacy, and patient-centered research to its 80,000 members across the US, western Europe, South America and Australia.

CreakyJoints Australia is now working on “Australianising” ArthritisPower, and hopes to gain research ethics approval by the end of the year.

ArthritisPower is useful because it lets the patient graphically represent how they’re doing, thereby validating their “invisible illness” and facilitating shared decision making, a spokesperson from CreakyJoints Australia tells The Medical Republic.

While Dr Grainger sees the value of ArthritisPower, she believes it has two major drawbacks.

Firstly, the app is not ideal for telehealth as does not collect the standard 28 tender and swollen joint counts used by rheumatologists, and secondly, it does not share data with rheumatologists in real time.

These two features are important because they can be used by rheumatologists to “treat to target”, or adjust the medications of a person with RA until there is very low, or no, disease activity.

“If you lived in the ideal world and you could see your rheumatologist when you had more active disease, perhaps you wouldn’t need to track your own disease activity,” she says. In the real world, however, rheumatologists only see their patients at arbitrary intervals, with months between appointments.

“So, we are not really able to support patients and interact with them at times where it may be more important or more meaningful in their healthcare journey,” Dr Grainger says.

An app that allows patients to make a clinically valid joint count and communicate that to their specialist doesn’t exist yet, so Dr Grainger has decided to make one.

Before designing the app, Dr Grainger interviewed patients and health practitioners, including rheumatologists, rheumatology nurses and GPs, about what they might want in an app. Dr Grainger also led a team of rheumatologists collecting data to explore if a patient-performed joint count was as accurate as a rheumatologist’s.

“The app is not publicly available in the app store, partly because we are still doing research on it,” she says. The hope is that patients will use this app in the future to send disease activity data to their doctor.

“And rheumatologists will either respond to it directly then and there if we need to, or just have it in the background to bring up when we next see them in clinic,” Dr Grainger says.

Turning this string of data points into something that is clinically useful takes work, which is problematic when specialists and nurses are already so busy.

“Everyone is working at capacity, so what are they not going to do so that they can do this?” asks Dr Grainger. “We haven’t quite nailed that yet.”

And then there’s the issue of equity; technophiles who can use their smartphone to check in with their rheumatologist anywhere at any time have an advantage over other patients, she says.

Dr Grainger, along with a physiotherapist colleague, Dr Hemakumar Devan, has also systematically reviewed apps to support self-management of chronic pain, something which is a daily struggle for many patients with arthritis.

There are some “beautiful” apps for meditation and mindfulness, such as the Headspace app, but these are often quite costly (Headspace has a $100 to $150 yearly subscription), she says.

“The other app we found rated quite highly for aspects of self-management of chronic pain was an app called SuperBetter,” says Dr Grainger.

SuperBetter is a free app that helps people set small goals to manage aspects of their health and wellbeing. It motivates behavioural changes in domains such as exercise, diet and mindfulness through gamification and peer support.

“It’s quite pretty and it’s designed with really good user experience and quite good cognitive science underneath it,” Dr Grainger says.

Formal reviews of health apps are essential because apps that don’t conform with clinical guidelines can carry risks for patients, Dr Grainger says.

Some apps are more risky than others. A a mindfulness app, for example, is unlikely to be harmful, but apps that give people advice about medication or displace face-to-face contact with doctors may be.

As with any other health advice, app recommendations must be tailored to the patient’s individual needs, and should support – rather than replace – traditional treatment plans, Dr Grainger says.

Many health apps downloaded by momentarily-motivated patients end up gathering virtual dust somewhere in the vaults of their app library.

“There are many health apps that are available today, however, many of them go unused after the initial download,” says CreakyJoints Australia.

Speaking with The Medical Republic from the carriage of a Russian train while travelling for the FIFA World Cup, Dr David Liew, a rheumatologist from Melbourne, said many apps for rheumatology lacked a clear purpose. “So much of it comes down to design,” he says.

While something like the National Ankylosing Spondylitis Society’s “Back to Action” app for patient exercises may be helpful, other apps try to achieve too much. If you want rheumatologists to recommend an app, “it needs to make their lives easier, not make their lives more complicated,” he says.

The sorts of tools that Dr Liew would really like to see, such as apps that remind patients to take their medications or apps that make it easier for doctors to report side effects, are not yet available in Australia.

Smartphones are a convenient tool for researchers looking to track disease trajectories. But sharing detailed data with clinicians is unlikely to improve patient outcomes, he says.

Patients with arthritis don’t need to take notes every week to remember how bad their symptoms are. Flares are not the kind of thing that patients easily forget, and paper works just as well as a smartphone for recording disease activity.

Simply put, “I don’t think you need an app for that”.