Helping patients with health risks and disease prevention requires a sophisticated, ecological approach

Helping patients with health risks and disease prevention requires a sophisticated, ecological approach. Looking at our own health behaviours is a case in point

An intriguing thing about being a doctor is the health contradiction we often live with. What we advise our patients and what we actually do ourselves can be miles apart.

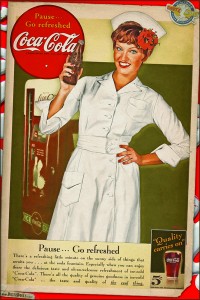

When I first became a medical student I remember the large amounts of coffee and Coke my colleagues and I seemed to consume. We were students, so we ate a lot of cheap carbohydrates to fill us up, and relied on sugar and caffeine to keep us going during those long study nights. In those days a lot of us did make the effort to go to the gym or swim or do some other regular physical activity, but then celebrations always involved alcohol, sometimes to excess.

On graduating we had a wage, but little free time, so the portable stimulants continued. Food, when we got to it, was frequently take-away and eaten too quickly. At medical education sessions we’d be offered pizza, and night-shift chips and chocolate were a staple. Exercise was usually restricted to running backwards and forwards across the hospital, with little time or energy for much else. On those precious days off the demands of study for a training program would fight with sleep for our attention.

Some years later, I vividly remember walking into a lecture theatre for a talk on major public health challenges. On the list were obesity and sedentary behaviours. As I waited to enter the ‘no food and drink permitted’ room, I saw student after student putting their empty soft drink cans, chip packets, chocolate wrappers and donut boxes into the bin near the door.

These were final-year medical students about to be unleashed on the health system. The contents of the bin suggested a complete disconnect between their own behaviour and notions of health.

My years in emergency departments only reinforced the belief that these behaviours were deeply embedded, even a sanctioned, part of the system.

Many days were so busy there wasn’t a chance to pause, let alone eat or drink anything – the nurses had a better union so got guaranteed breaks that they ensured they took – and on those scary night shifts, consuming sugar and fat was just what you did.

Those formative medical years created some bad habits.

Lack of sleep

Another issue was sleep, or rather the lack thereof. The nine-to-five routine is not a part of hospital-based training or practice. Covering the evening page on the wards after an already flat-out day, or being on a surgical team that never seemed to sleep, were all part of the experience. And approaching those weeks of night shift was like preparing for battle.

Competition for getting in with your preferred specialty was an elite sport, not always played by the rules. And continuity of patient care was a phrase we could all recite but struggled to practice because of the high number of patients, short bed stays, and frequent rotations.

General practice seemed like a sane option. Regular hours, personable colleagues, more holistic care, you could train and/or practice part-time, with a good amount of portability of skill set, and a specific interest, too, if that’s what you chose.

No more night shift, or hospital hierarchies. Weekends off were a choice, and there was the luxury of a room of your own. A chock-full day would usually be on the cards, but there was the real prospect of a hot cuppa in there, and probably some lunch, even if eaten late. And continuity of patient care was a given.

All up, a healthier choice?

In the mirror

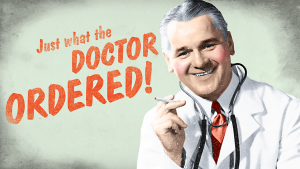

What’s often said about patients is that they simply need more education to make healthier choices. We go to great lengths to provide this information, and there is now a huge industry in patient-information services. If patients just had the information in a format they found easy to relate to, and were supported with putting that into action, then they would more likely make better choices, and that would result in better health outcomes.

Yep, it’s all about more education.

Doctors spend around 12 years in medical training before obtaining fellowship. That’s a lot of education.

The fact that we have all that education, specifically about health, should make us a very healthy lot. We, of all people, know what to do, and what to avoid, when it comes to healthy choices. So, barring the minority who have a hereditary predisposition, the rest of us should have optimal BMI, BP, BSL, cholesterol, mental health and so on.

And the fact that the system we trained and work in taught us bad habits should be irrelevant. We have the education – more than anyone else – to ensure we make the best choices, and radiate optimal health. So, looking in the mirror and honestly seeing what’s reflected back should raise no concerns about our health whatsoever.

Smoking doctors

A case in point is doctors who smoke. Albeit at one far end of the health choice spectrum, research suggests that about 5% of doctors in Australia, New Zealand, Canada, the United States, and United Kingdom still smoke cigarettes.

Numbers have been steadily falling since the 1970s in these countries. However, in China 32% of male doctors currently smoke (apparently no female doctors do), in Italy it’s 28% (32% among men), and in Turkey or Bosnia and Herzegovina around 40% of doctors smoke.1

As an illustrative point, that any doctors continue to smoke raises interesting questions about the emphasis on education to change health behaviours. If adopting healthy habits was simply a matter of education, there shouldn’t be any doctors who smoke.

If a medical degree and working in the health system doesn’t stop doctors smoking, then what factors are contributing to this choice? And how can they be most effectively identified and worked with?

Ecological approaches

The literature has done some deep-diving into the question of effectiveness of providing health information to patients and the impact on health outcomes. And the findings make sobering reading. Just making patients more knowledgeable about their disease doesn’t work. A large meta-analysis published about behavioural interventions for Type 2 diabetes highlights this.

The authors concluded that traditional didactic programs aimed at improving patients’ knowledge of their disease were ineffectual, and the emphasis, instead, should be on behavioural approaches that provide patients with the skills and strategies required to promote and change their behaviour.2

This might go part way to explaining why some doctors choose to smoke. Their knowledge of the harmful effects of tobacco smoking is indisputably high, but their choice to smoke clearly isn’t determined by this. Something else is going on.

More recent approaches recognise the complex context in which health choices are made. Current perspectives are seeing a shift away from ‘just give them more education’ messages towards more sophisticated strategies. These newer approaches embrace two main tactics:

- Behavioural interventions aimed at providing patients with the skills and strategies required to promote and change their behaviour, and;

- Ecological approaches that investigate and develop responses to the system-level contributors to human health e.g. from urban design, food quality and access, intergenerational knowledge transfer, and structure of workplaces, to the impacts of financial stress, lack of control over personal decision-making (such as being a worker on the lower rung of the work hierarchy), racism, fear of violence, housing insecurity, and social isolation.

Often working in tandem, these wider-lens approaches recognise that individual health decision-making is not made in isolation of the context in which a person lives or the health of broader social structures and practices.

As the Australian Prevention Partnership Centre at the Sax Institute in Sydney puts it:

“A lot of work in prevention has targeted individual behaviour, but many things, including where we work, eat, play and live, and our access to work and education, all affect our health. It is not enough to simply urge Australians to eat better and exercise more. We need to look at the wider systems that can help or hinder behaviours that cause chronic health problems. We need to look in depth at our communities, our food systems, our environments and workplaces and how each of these interacts to create communities in which healthy behaviours are the easier, more sustainable choices.”3

The Sax Institute is a national leader in promoting the use of research evidence in health policy. They aim to be the bridge between researchers and health decision makers, giving each the tools to work more closely together to benefit all Australians.

They get the ecological approach, and see its considerable benefits.

So, using this approach, why might a doctor smoke? It’s certainly not because they don’t know the harms associated with smoking. Despite the negative associations with being a doctor who smokes, they still do it. Is it about relieving their stress? Medicine is a high stakes profession with a ‘suck it up’ culture. Going out for a smoke might be the only way they can legitimately leave a stressful workplace for a few minutes every hour or two, a brief respite and easily repeatable means of deriving pleasure in a high-demand environment. Maybe it’s a response to the awareness that good people get sick no matter what health choices they make, so they might as well have a little pleasure along that unpredictable journey, or a powerful example of the ‘it won’t happen to me’ syndrome.

Or perhaps it’s a “f*** you” to the individual-focused pleading or blaming health messages that can have the reverse effect from what was intended. Could it be a “don’t tell me what to do” response – starkly illustrated by the finding that some customers buying cigarettes with graphic warning labels would jokingly ask for “a packet of emphysema or lung cancer, please”.

Maybe the doctor is trying to juggle the demands of a 24-hour roster, with the inevitable disrupted sleep and diet, while trying to maintain a healthy home life, and choosing to smoke offers a small sense of control and release. Or they feel like a cog in the wheel of a massive health system with practices which neglect the effects of the environment of the workplace, e.g. crowded work areas, unreliable equipment, no natural light, poor food options on site, the emphasis on making sure the systems flows smoothly, not necessarily with respect to being able to provide optimal health care. In other words, a disease-management environment rather than a health-promoting one.

Perhaps it’s an indication of just how disconnected modern medicine has become from the broader contexts in which health occurs. Whatever the reasons, thinking this

scenario through prompts important thought about how we might better approach our patients’ needs.

Tackling these wider influences and issues is hard. It’s easier just to give the information sheet and move on to the next patient. We all know that feeling. But if we genuinely want to improve health, we need to be willing to get behind and underneath the wider reasons people make the health choices they do – to ask why doctors smoke – to really make a sustainable difference.

Dr Ursula King is Medical Editor, The Medical Republic, and a rural emergency practitioner

References:

- Smith, D.R.; and Leggat, P.A. The historical decline of tabacco smoking among Australian physicians: 1964-1997. Tob Induc Dis. 2008; 4(1):13.

- Health Quality Ontario, Behavioural Interventions for Type 2 Diabetes, Ont Helth Technol Assess Ser. 2009; 9(21):1-45.

- https://www.saxinstitute.

org.au/r-work/preventing-chronic-disease