The release of specialist outpatient waiting times caused outrage when it was revealed some patients had been waiting more than 16 years

The recent release of specialist outpatient waiting times by the new South Australian government caused outrage when it was revealed some patients had been waiting more than 16 years for an appointment.

This is not a new problem. A 2000 Senate Committee Report cited consumer concerns about long outpatient waiting times, as did the 2005 Forster report into Queensland’s health system.

Access to timely care is the cornerstone of an efficient and effective health-care system. Delays decrease patient satisfaction, prolong periods of pain and discomfort, and create uncertainty for patients. Worse, a patient’s health might deteriorate while waiting with an undiagnosed condition.

Read more:

Which are better, public or private hospitals?

Room for improvement

Historically, much of the conversation on waiting times at public hospitals has been about elective surgery. While efforts to report and reduce waiting times for elective surgery have been established nationwide, these figures only account for the time from a specialist appointment to the date of surgery.

This obscures the sober reality of even longer waits from GP referral leading up to the initial specialist appointment. This unreported wait is known as the “hidden” waitlist.

Currently, the quantity and quality of publicly available data on outpatient specialist clinics vary significantly between states, making it difficult to do national comparisons. Victoria has the most comprehensive data, reporting waits for the average patient, as well as how long the 10% of patients with the longest waits spent on the list for each specialty and urgency category.

While Queensland and Tasmania have also published data on all referral categories, they use different measures. South Australia has only published average wait times for non-urgent referrals.

States also use different urgency categories to triage outpatient referrals. In Victoria, referrals are stratified into two categories based on queuing theory, which suggests the most efficient form of prioritisation is one with the fewest possible categories. Meanwhile, other states (WA, Tasmania and Queensland) function with three priority categories.

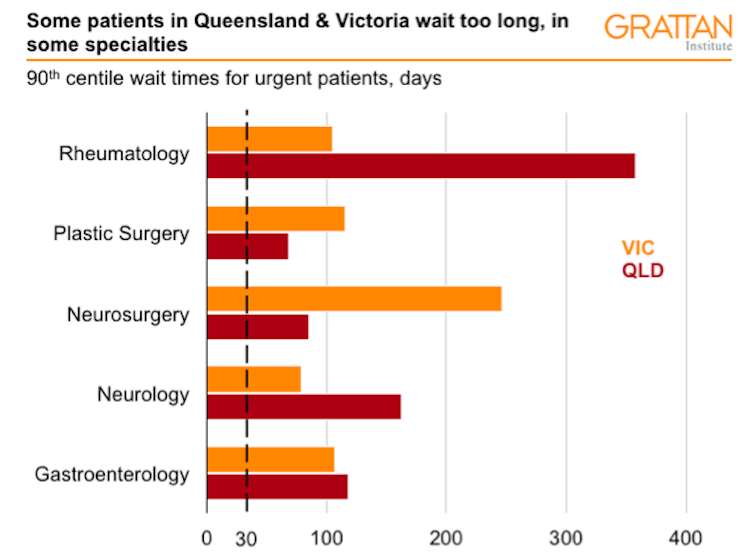

These different approaches to reporting make it impossible to compare states. Some 10% of patients wait more than three months in many Queensland clinics, and more than two months in Victoria.

Queensland Health Quarterly information for Specialist Outpatient 2018, Victorian Health Services Performance Statewide Performance Data. Note: The clinically recommended wait time for Urgent (Category 1) patients is <30 days. The 90th centile wait time is the within which 90% of patients attended their first appointment., Author provided

Why do such long wait times exist?

The number of specialists available and the hours they choose to work in public hospitals affect the number of clinic appointments available. In aggregate, 48% of specialists work across both public and private sectors, 33% work only in public and 19% work only in private practice.

A study revealed that on average, orthopaedic surgeons and rheumatologists spend more than 70% of their time in private practice. Private practice generally offers higher incomes to doctors.

With such long wait times, patients who can afford it may turn toward private specialist services to skip the queue, leaving patients who cannot afford the high out-of-pocket costs charged by specialists to wait.

The burden of out-of-pocket costs also falls disproportionately on those with multiple diseases, the least disposable income and older households, excluding them from accessing more timely care in the private sector.

Read more:

Explainer: why do Australians have private health insurance?

What can be done?

Some health services have implemented strategies to reduce outpatient waiting times. This can include using more allied health services where appropriate. For example, using physiotherapists to see patients in orthopaedic clinics can help patients get non-surgical treatment for their condition earlier.

Other good solutions include a non-contact first specialist appointment, where a specialist looks at a patient’s clinical notes and sends their recommendation to the referring GP.

States need to address long outpatient waits. And they need to be accountable for doing so.

We need better data on outpatient specialist clinics accessible in all states. Ideally, the data reported would be based on a national standard, as we currently do for elective surgery and emergency services.

Read more:

Are private patients in public hospitals a problem?

![]() Tessa Tan, Grattan Institute Intern and Bachelor of Medicine student contributed to this article.

Tessa Tan, Grattan Institute Intern and Bachelor of Medicine student contributed to this article.

Stephen Duckett, is Director, Health Program, Grattan Institute

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.