By almost all measures, Australia’s strategy to eliminate hepatitis C is on track. But we cannot afford to be complacent

After breakfast each morning, Jane stands in the kitchen and with a glass of water in one hand and a big, white chalky pill in the other. One a day, for 12 weeks. Not used to swallowing any pills other than the occasional fish-oil capsule, the size took a little getting used to. But that is her only complaint.

She is taking Zepatier, a combination of two agents that stop her body from producing the proteins that the hepatitis C virus need to multiply. Doctors told her they were 98% sure that if she took this direct acting antiviral for three months she would be cured of a virus that had accompanied her for three decades.

Jane has genotype 4, one of the rarest strains in Australia, and after the drugs for types 1,2 and 3 were added to the PBS in early 2016 she would periodically return to her GP asking when medication for her type would be ready. Her partner, Colin, shares this strain of the virus. He’s already been treated and cleared of the chronic infection. Jane will find out if she is clear on Boxing Day.

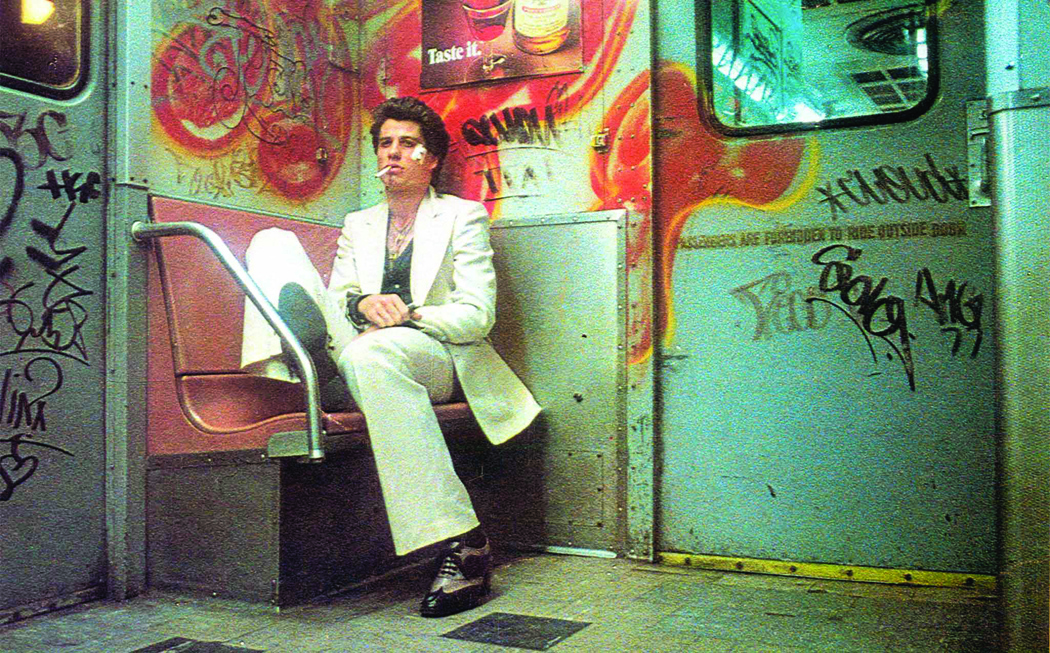

Colin is a teacher. Jane is retired now, but volunteers in the community and takes photographs for fun. They are the typical image of hepatitis C in Australia – boomers who grew up in the 1970s and 80s when Australia’s love affair with heroin was in full bloom.

She sometimes wonders why she and Colin picked up the virus and why other friends, who injected far more frequently, had not.

“We hardly ever shared [needles]. When we did, it was only under adverse conditions, and we sterilised the needles,” she says, before catching herself. “Well, we thought we sterilised them anyway.”

Because the idea of hepatitis C goes hand-in-hand with less politically appealing groups – injecting drug users and prisoners, for example – it has been more difficult to mobilise support and secure funding from governments than for other chronic conditions, such as diabetes or cardiovascular disease.

Yet despite this, the recent development of “blockbuster” drugs that are well-tolerated, highly effective and require a short duration of therapy has kicked off a serious effort to eliminate the infection, and Australia is leading the way by committing huge resources to the purchasing and distribution of the cure.

Associate Professor Jason Grebely, a leading researcher on hepatitis C at the Kirby Institute, called the new drugs “one of the greatest medical breakthroughs in decades”.

“Australia could be one of the first high-income countries with a considerable hepatitis C burden that could actually achieve elimination, and could do this between 2026 and 2030,” says Professor Grebely, a Canadian who has spent the last decade living in Australia.

For the Australian healthcare system, and Australians themselves, this may be one of the best success stories in our public-health history.

Open access to a new hepatitis C cure has had a powerful effect on people carrying around a stigmatising disease, one that is often kept secret from friends and family and seen by some as a time bomb.

“It’s a really strange part of your psychology,” Jane says. “You have this stuff in the back of your head. You don’t think it affects you in any way, shape or form, but when they were offering a cure…”

The threat of future damage to her liver, on top of the increased risk associated with hepatitis C, was the reason Jane gave up drinking alcohol. It was also part of the reason Colin gave up drinking. But in terms of other therapies, they were never tempted to give previous interferon-based treatments a try. Especially after watching a friend endure it.

“It was horrendous,” Jane says.

There were mood swings, he was depressed, and he said it was what he imagined chemotherapy would feel like. “He felt sick as a dog.” And after 12 months of this, the treatment failed to work anyway.

These interferon-based therapies were so unpopular that in the two decades they were available only 2000 or 3000 people started treatment each year.

“Then it felt like, all of a sudden, they had this magic cure,” Jane says. “I was just elated.”

In the 10 months following the PBS listing of the new medications, Australia experienced a 12-fold increase in the number of people starting therapy.

By now, an estimated one in seven people living with chronic hepatitis C have been cured by the new drugs, according to Professor Gregory Dore, infectious disease physician and head of the viral hepatitis clinical research program at the Kirby Institute.

The uptake was particularly high among those with advanced liver disease, with numbers indicating more than one in three patients who had developed cirrhosis from their infection may now have been cured, he told audiences at the Australasian Viral Hepatitis Elimination Conference in Cairns in August.

When clinicians and researchers talk about the Australian experience with hepatitis C cure they use words such as “impressive”, and otherwise measured and restrained health professionals use terms such as “miracle drug” and “breakthrough” to describe the new medications.

Excitement and optimism abounds.

“It’s been revolutionary,” says Professor Geoff McCaughan, head of Liver Injury and Cancer Program at Sydney’s Centenary Institute.

“I don’t think there’s been anything like it in the health sector in terms of the rollout of a cure of a chronic and longstanding illness.”

In 2016, around 1% of the Australian population was estimated to have the disease, roughly 230,000 people, before the drugs became available. And within the first year and a half since it became government subsidised, figures suggest that number is now down below 200,000.

So how did Australia become the world leader, on track to not only reach the World Health Organisation’s goal of virtually eliminating the virus by 2030, but possibly even beating it by four years?

Professor Grebely says there are four major features that make Australia stand out from other countries.

“The first thing is really the availability of access for all for patients,” he says. “That was absolutely critical.”

This means that anyone can receive treatment, irrespective of disease stage and irrespective of recent drug or alcohol use.

“The second thing is having a strong involvement and advocacy from the affected community in collaboration with clinicians, policy makers and government.”

It was this strong voice from the affected community and leadership from key clinical advocates that overwhelmingly pushed for universal access, he says, unlike many other countries which have prioritised or limited the medication to people with more advanced liver disease or without drug and alcohol use.

“The third thing that’s incredibly important is the ability to have a broad practitioner base,” Professor Grebely says. “This allows drug and alcohol specialists and general practitioners to prescribe.”

Critical to this has been the education and training provided by groups such as the Australasian Society for HIV, Viral Hepatitis and Sexual Health Medicine in preparing clinicians for the treatment rollout, combined with the broad agreement from health professional groups in creating clear guidelines to instruct prescribers in how to treat.

Australia was naturally well prepared to wield these drugs to their full capacity. Through decades of concerted screening efforts, an estimated 82% of the population who have chronic hepatitis C know they have it. Identification is a major step in elimination.

Being on our fourth iteration of a national strategy against hepatitis C, in addition to a 2015 parliamentary inquiry, is incredibly important in establishing hepatitis C’s place on the health agenda, Professor Grebely says.

The national strategy codified tangible targets and goals, as well as drawing attention to priority populations, making it clear where resources should be allocated and how to measure success.

It has a number of different objectives, including reducing hepatitis C incidence, reducing risk behaviours associated with transmission of hepatitis C, which includes increasing provision to needle and syringe program access, increasing appropriate management and care, reducing burden of disease and eliminating the negative impact of stigma and discrimination on people’s health, Professor Grebely says.

“And it was built through a partnership approach between the government, providers, researchers, and the affected community, so there is buy-in from the government.”

By comparison, many other countries are only now creating their first national strategies.

In another clever move, the policymakers decided to not only move the drugs from a section 100 listing to a section 85 listing, but to dual list them. Making them available as a section 85 drug was critical in enabling GPs to prescribe them without the additional training required under the section 100 Highly Specialised Program – a stipulation which experts believe may have delayed treatment by months or even years.

But because prisoners are not eligible for PBS-funded medication, the dual listing enabled clinicians to prescribe them as a section 100 drug to ensure that it was subsidised by the federal government. Otherwise state governments would have been left to foot the bill, potentially delaying or impeding access to the drugs.

It is this commitment to deliver the cure to populations such as prisoners and those who inject drugs, is another major success in Australia’s mission to reach the elimination targets, Professor Grebely says.

Stemming the rising long-term morbidity and mortality has been achieved by taking a two-pronged approach of preventing new infections but also preventing advanced disease, he says.

It is “pretty amazing” to think that perhaps over 70% of people with cirrhosis have already been treated, he says. “Now we’re left with this broader population of individuals who have more mild disease, which has the potential to reduce the rising burden of liver disease.”

Australia is listed among the top nine countries on track to achieve the WHO elimination targets, according to non-profit hepatitis research group Polaris Observatory, alongside Germany, Qatar, Georgia, Japan, the Netherlands, Egypt, France and Iceland.

But it’s not easy to make comparisons across countries when they can be so vastly different. For example, Iceland only has 800 to 1000 people living with hepatitis C.

Nonetheless, Professor Grebely and Professor Dore recently wrote a journal letter comparing the German system to the Australian one, highlighting the benefits of our bargaining power in bringing prices down.

The Australian government finally announced the approval of the new direct acting antivirals in December 2015, after protracted negotiations with pharmaceutical companies.

Frustrations had grown among clinicians and patient advocacy groups as they watched overseas patients being cured while the government here appeared to drag its feet. The situation was so dire for some that a Dallas Buyers Club scenario even emerged, as patients chose to import cheaper drugs from manufacturers in India and China instead of waiting.

But eventually, five days before Christmas, the then-health minister Sussan Ley announced the PBS approval of the new direct-acting antivirals, earmarking $1 billion for the drugs over the first five years.

The Department of Health and the drug manufacturers have largely kept mum on the specifics of the arrangement, but they are known to have entered into a risk-sharing agreement to ensure prices were well below the $80,000 or more patients in the US were being charged.

A major feature of the deal was that there would be no cap on treatment numbers but there would be a maximum cost, providing an incentive for the government to treat as many patients as possible to drive prices lower.

Without knowing the exact details of the agreement, Professor Grebely and Professor Dore estimated how much the Australian government was able to drive down the price.

Given 32,400 patients with chronic hepatitis C were treated in the first 10 months between March and December of last year, and the cost to the government was in the range of $250-$300 million, the price of each course of treatment would be between $7700 and $9300 per person, they calculated.

“It’s one of the lowest high-income country prices negotiated in the world,” Professor Grebely says.

On the other hand, they calculated that prices in Germany were around 66,000 euros per course. That’s a 10-fold disparity in drug pricing, because each private health insurance company had to negotiate with the pharmaceutical company, he notes.

This drives home the value of a central federal body such as Australia’s Pharmaceutical Benefits Advisory Committee in ensuring access to all.

In awarding a public service medal to Adriana Platona earlier this year for her work negotiating with pharmaceutical companies on behalf of the government, the Governor General said the PBS listing of the drugs was “a defining event in Australia’s PBS history and the future health of the nation”.

While countries such as Canada, France and Portugal have also managed to negotiate lower prices to improve access to all, Professor Grebely says he is surprised that more countries in Europe hadn’t been able to work together to achieve greater purchasing power and negotiate reduced prices similar to Australia.

“High direct acting antiviral drug pricing has the potential to impact on clinician attitudes and lead to prioritisation,even in settings such as Germany where liver disease state restrictions are absent,” he and Professor Dore wrote in their letter.

“For example, people who inject drugs (PWID) may be regarded as a lower priority due to perceptions of poorer adherence and HCV reinfection, despite evidence to suggest PWID treatment is both highly effective and cost-effective due to individual and population (treatment as prevention) benefits.”

When asked whether Australia is falling behind in any metric when compared with other countries, Professor Grebely pauses, struggling to answer.

“We think about this a lot, but if you think of what Australia has in terms of the health system to make this happen, a lot of the pieces are there.”

For Jane and Colin, medications they receive free from the local hospital pharmacy have brought no vomiting and no mood disturbances. Jane even searched for the feelings of fatigue, headache and nausea that were known to sometimes accompany the treatment, but found nothing.

Soon, in all likelihood, they will be living hepatitis C-free lives.

So it has been a success story. The culmination of multiple puzzle pieces of a health system and community working well and in tandem.

But Australia also has the benefit of being a high-income country with a relatively small population, and we can’t afford to get complacent.

Experts warn that without stepping up, it’s possible we may not reach the 2030 elimination target.

In his talk at the Cairns conference, Professor Dore said that if treatment rates continued to plateau and even drop off, the 65% reduction in hepatitis C mortality might be achieved by 2029, but the goal of treating 80% of the infected population might not be achieved until 2031. Improving efforts in more marginalised populations was vital.

Professor Grebely agreed with the need for renewed efforts.

“I feel so fortunate to have lived in Australia in the last 10 years during this period of excitement, because the world is looking to Australia with envy.”

“The majority of countries have restrictions based on disease stage, they don’t allow general practitioners to prescribe, there are restrictions based on drug and alcohol use, they don’t have national strategies, they don’t have guidelines for practitioners in terms of prescribing, they don’t have funding for community-based organisations to do their work and they don’t have the ability to treat hepatitis C in prisons.”

“All those things are happening in Australia,” he says.

“But I’m not trying to make it sound like Australia is the be all and end all,” he says. “We’ve made a lot of investment in the funding of the of the actual medications, but there needs to be a bit more thought about how to provide funding for health services to provide broadened access to HCV care and primary care because there hasn’t been a coinciding increase in funding for services.”

* Some names have been changed