40% of women in their child-bearing years aren’t consuming enough iron.

FORTY PERCENT OF AUSTRALIAN WOMEN AGED BETWEEN 14 AND 50 YEARS HAVE INADEQUATE INTAKES OF DIETARY IRON.1

The estimated average requirement (EAR) for iron, used to estimate the prevalence of inadequate intakes within a population group, is 8mg per day for females aged 14 to 50 years.2

While the recommended dietary intake (RDI), used to evaluate whether iron intake in an individual’s diet is adequate, for females is:

- 15mg per day aged 14-18 years

- 18mg per day aged 19-50 years

- 27mg per day during pregnancy

Available estimates suggest about one in five women of childbearing age suffer from some form of iron deficiency.3 The prevalence of iron deficiency is more common in women who are pregnant or breastfeeding, have heavy periods, or don’t eat much meat. Low iron stores can affect mental and physical wellbeing.4-6

Iron-rich food sources – bioavailability is key

Although cereals make the greatest contribution to total iron intake, beef and lamb are the most bioavailable sources of dietary iron in the Australian diet.7

In the 2011-2012 National Nutrition and Physical Activity Survey7, major contributors of total iron intake included ready-to-eat breakfast cereals, many of which are fortified with iron (17%), bread (10%) and cereal-based products and dishes such as pizza, cakes, biscuits and pastries (16%). The contribution of beef and lamb was 12%.7

Absorption of dietary iron is about 18% from omnivore diets compared to about 10% from a vegetarian diet. To compensate for the lower bioavailability of iron from plant foods, higher total dietary intakes are recommended for people following a vegetarian or vegan diet.2

Several studies have shown that consumption of foods containing haem iron, including meat, poultry and fish, are the main dietary predictors of iron status.8,9 The role of meat, poultry and fish as sources of dietary iron are particularly important in women on energy restricted diets.10,11

Knowledge and consumption – gaps vs dietary guidelines

Consumption of red meat by Australian women usually occurs in a home-prepared evening meal, typically three to four times a week. The average per capita consumption of red meat in women is below amounts recommended in the Australian Dietary Guidelines12 (50g vs. 65g per day, cooked weight, respectively).13

There is some evidence that improving nutrition knowledge amongst young women, which is generally low to moderate, may help to improve not only dietary iron intake but also intake of zinc, omega-3 and vitamin B12.14-16

How can GPs help patients follow an iron-rich diet?

Iron-rich food sources

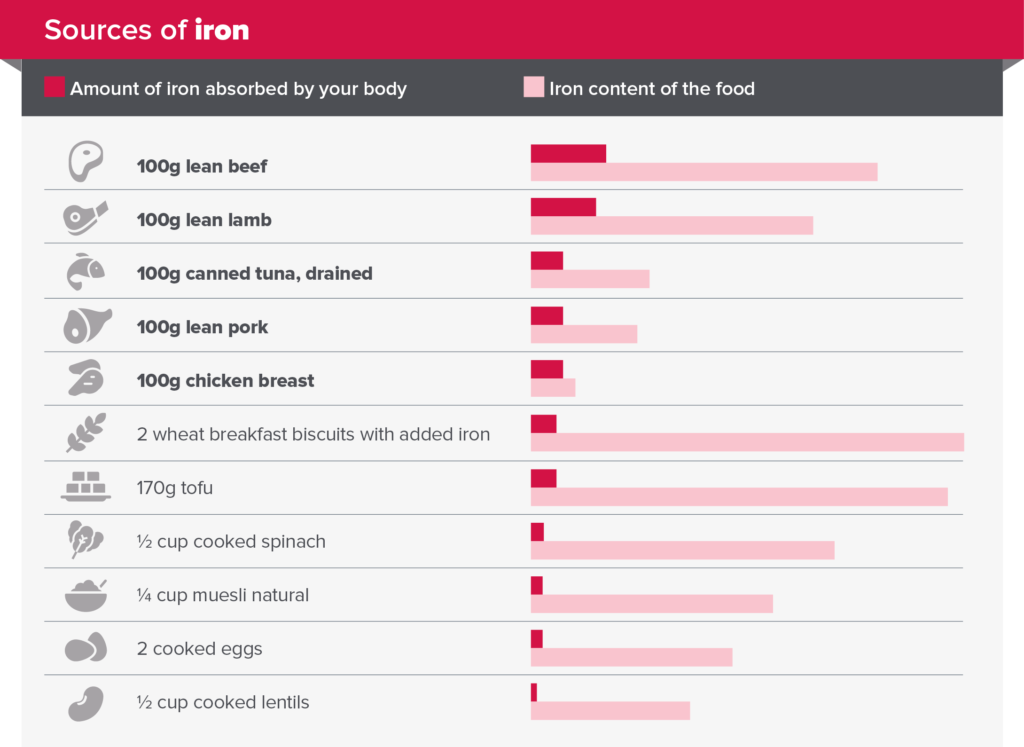

The graph below makes it easy to explain how more iron is absorbed from meat, fish and poultry than iron-fortified breakfast cereals and spinach despite having lower amounts of total iron because they contain haem iron.

- About 25% of haem iron is absorbed by the body compared to 5 to 15% from non-haem iron.17

- The redder the meat, the higher the iron content. The proportion of haem iron in beef and lamb is approximately 60%, 40% in pork, 30% in chicken and 25% in fish.18

Iron-rich, healthy meal ideas

- Amounts of red meat recommended in the Australian Dietary Guidelines12 can be eaten across three to four healthy, balanced meals a week.

- It is important to suggest a variety of different meals with portion sizes ranging from 100 to 200g raw weight per serving (equivalent to 70g to 160g cooked weight).

- For vegetarian options, include foods that provide around 25mg of vitamin C to assist with the absorption of non-haem iron.17

Combining a plant-based source of iron (such as tofu, spinach, or grains) with a source of vitamin C (such as berries, oranges, tomatoes, or broccoli) can help optimise the absorption of non-haem iron.

How to order free resources

Meat & Livestock Australia’s nutrition resources provide practical tips for planning and serving healthy, balanced meals. These patient-friendly resources include portion guidance for meeting iron, protein and carbohydrate needs for different dietary requirements and life stages.

Click here to view and order copies of the patient-friendly resource on iron-rich foods.

Who is MLA?

Meat & Livestock Australia (MLA) is an industry owned Rural Research and Development Corporation that delivers marketing, research and development services to Australia’s red meat and livestock industry. Our activities in nutrition research and communications aim to support the consumption of Australian red meat in healthy, balanced meals. For more information, visit MLA Healthy Meals.

References

- Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2015 Australian Health Survey: Usual Nutrient Intakes [Australian Health Survey: Usual Nutrient Intakes, 2011-12 financial year | Australian Bureau of Statistics (abs.gov.au)] Accessed 9 March 2022.

- National Health and Medical Research Council and New Zealand Ministry of Health, 2006, Nutrient Reference Values for Australia and New Zealand https://www.nrv.gov.au/nutrients/iron, accessed 9 March 2022.

- Ahmed F, Coyne T, Dobson A, McClintock C. Iron status among Australian adults: findings of a population-based study in Queensland, Australia. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr 2008;17:40-7.

- Greig A et al. Iron deficiency, cognition, mental health and fatigue in women of childbearing age: a systematic review Journal of Nutritional Science 2013;2;E14. doi:10.1017/jns.2013.7.

- Lomagno KA et al. Increasing iron and zinc in pre-menopausal women and its effects on mood and cognition: a systematic review. Nutrients 2014; 6:5117-41. doi:10.3390/nu115117.

- Pasricha SR, Flecknoe-Brown SC, Allen KJ, Gibson PR, McMahon LP, Olynyk JK, et al. Diagnosis and management of iron deficiency anaemia: a clinical update. Med J Aust 2010;193:525-32.

- Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2014, Australian Health Survey: Nutrition First Results – Foods and Nutrients, 2011-12, ‘Table 10: Proportion of Nutrients from food groups‘, data cube: Excel spreadsheet, cat. no. 4364.0.55.007.

- Heath A, Skeaff C, O’Brien S, Williams S, Gibson R. Can dietary treatment of non-anemic iron deficiency improve iron status? J Am Coll Nutr 2001;20(5): 477-484. doi:10.1080/07315724.2001.10719056.

- Patterson A, Brown W, Roberts D, Seldon M. Dietary treatment of iron deficiency in women of childbearing age. Am J Clin Nutr 2001;74(5):650-56. doi:10.1093/ajcn/74.5.650.

- Cheng H, Griffin H, Byrant C, Rooney K, Steinbeck K, O’Connor H. Impact of diet and weight loss on iron and zinc status in overweight and obese young women. Asia Pac J Nutr 2013;22(4):574-82. doi: 10.6133/apjcn.2013.22.4.08.

- O’Connor H , Munas Z, Giffin H, Rooney K, Cheng HL, Steinbeck K Nutritional adequacy of energy restricted diets for young obese women. Asia Pacific Journal of Clinical Nutrition 2011;20:206-211.

- National Health and Medical Research Council. Australian Dietary Guidelines [Internet]. Canberra (ACT): NHMRC; 2013 [cited 2022 March 9]. Available from: https://www.nhmrc.gov.au/adg

- Sui Z, Raubenheimer D, Rangan A. Consumption patterns of meat, poultry, and fish after disaggregation of mixed dishes: secondary analysis of the Australian National Nutrition and Physical Activity Survey 2011–12. BMC Nutr 2017;3:52. doi:10.1186/s40795-017-0171-1.

- Fayet F, Flood V, Petocz P, Samman S. Avoidance of meat and poultry decreases intakes of omega-3 fatty acids, vitamin B12, selenium and zinc in young women. J Hum Nutr Diet 2014;27:135-142. doi:10.1111/jhn.12092.

- Leonard AJ et al. The effect of nutrition knowledge and dietary iron intake on iron status in young women. Appetite; 2014;81:225–231.

- Lim K, Booth A, Szymlek-Gay EA, Gibson RS, Bailey KB, Irving D, Nowson C, Riddell L Associations between dietary iron and zinc intakes, and between biochemical iron and zinc status in women. Nutrients 2015;7:2983-99. doi.org/10.3390/nu7042983.

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations & World Health Organization Requirements of vitamin A, iron, folate and vitamin B12: report of a joint FAO/WHO expert consultation. Rome:Lanham MD: FAO; UNIPUB [distributor]; 1988.

- Schönfeldt H and Hall N. Determining iron bioavailability with a constant heme iron value. Journal of Food Composition and Analysis 2011;24:738-740.