As voluntary assisted dying laws come into operation in New South Wales, what do GPs need to know?

As voluntary assisted dying laws come into operation in NSW, 34,000 more GPs will need to be aware of their role in VAD.

On 28 November 2023 voluntary assisted dying (VAD) laws came into effect in New South Wales (NSW), meaning that VAD is now operating in all Australian States. It is still illegal in the Australian Capital Territory (ACT) and Northern Territory (NT), but a new Bill to legalise VAD is being debated by the ACT Legislative Assembly.

The commencement of VAD in Australia’s most populated State will impact an additional 34,000 GPs,1 who will need to know their roles and obligations under VAD laws, especially when caring for older people.

According to ELDAC End of Life Law Toolkit developer and lawyer Penny Neller, each State’s VAD laws are similar but there are some key differences in what GPs and other health professionals can say and do in relation to VAD, depending on where they practise.

“GPs have a significant role in caring for and supporting older people at the end of life, so it’s important they know their legal obligations in relation to VAD,” Ms Neller said.

“Even if a GP consciously objects or chooses not to be involved in VAD, there are still legal requirements they must follow.”

Penny is one of a team of legal experts based at the Queensland University of Technology (QUT) who have developed educational resources for GPs, nurses, and other health professionals to support them in understanding VAD laws when caring for people receiving aged care.

These evidence-based resources are available for free as part of End of Life Directions for Aged Care (ELDAC), a $15.9 million palliative care initiative funded by the Australian Government Department of Health and Aged Care.

Roles GPs can perform in VAD without mandatory training

“All GPs can perform some roles associated with VAD, even if they have not undertaken mandatory VAD training in their State,” Ms Neller said.

“For example, they can provide information about VAD if a patient asks and receive a person’s initial request for VAD.

“They might also be present (if a patient asks) when that person self-administers the VAD medication.”

Roles GPs can perform in VAD with mandatory training

“If a GP wants to provide VAD, they must undertake mandatory training provided by their State health department. They must also meet requirements about their registration and years of experience, and in some States must also have expertise in the person’s illness or condition,” Ms Neller said.

“GPs who are trained and eligible to provide VAD may choose what roles they perform. Some GPs may want to be involved in all aspects, for example, assessing a person’s eligibility for VAD, prescribing VAD medication, and administering VAD medication to a person. Others may choose to do only some of these.”

Communicating about VAD

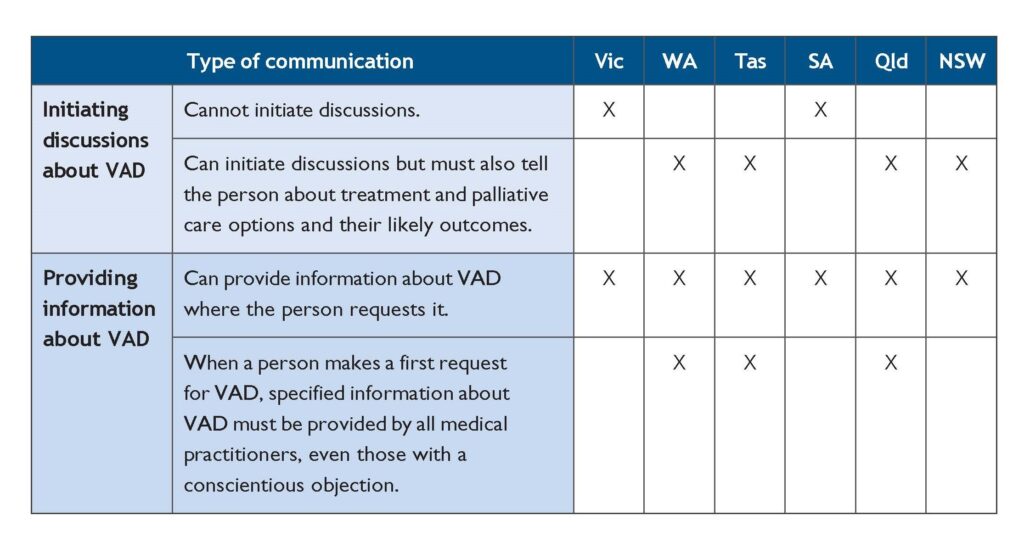

“It’s important for GPs to be aware of the restrictions on when they can start a discussion about VAD with a patient. In Victoria and South Australia, GPs cannot initiate VAD discussions with a person. In the other States, they can initiate discussions, so long as they also discuss the person’s available treatment and palliative care options, and their likely outcomes,” Ms Neller said.

“Despite these restrictions, GPs can provide information about VAD if a person requests it.

“In some States, where a person requests VAD for the first time (a first request), GPs must also provide specific types of information to the person.”

Conscientious objection

“All health professionals have the right to conscientiously object to participating in VAD,” Ms Neller said.

“However, in some States, objecting GPs may still have certain legal obligations, such as to provide information to a person requesting VAD. These laws can be complex, but are explained in detail in our free End of Life Law Toolkit.”

Continuation of palliative care

“Most people who request VAD also receive palliative care. They can continue to receive palliative care, medical treatment and other end of life services up until their death,” Ms Neller said.

“VAD is different from providing pain and symptom relief. It is not VAD where a person unintentionally dies after receiving medication to relieve their pain (e.g., morphine). This is because the health practitioner’s intention was to relieve pain, not hasten the person’s death,” she said.

The patient’s family, carer, or substitute decision-maker

“If a patient’s family, friend, carer, or substitute decision-maker asks a GP for information about VAD, the GP can give information. However, a request for VAD cannot be made by any other person on behalf of your patient,” Ms Neller said.

“This is to ensure that a patient’s decision to access VAD is voluntary, with no pressure from another person.”

For further information about VAD including free downloadable fact sheets and resources for GPs and other health professionals caring for older Australians, visit the End of Life Law Toolkit on the ELDAC website, www.eldac.com.au.

References: