There's a vicious circle that keeps pushing up premiums.

Since 2015, the share of younger people (aged 20 to 39) with private health insurance has dropped from 24% to 22%.

People in this age group contribute more in insurance premiums than they claim in pay-outs. So this decline ends up pushing prices up for the 44% of Australians with private insurance.

And new private health insurance coverage data shows this trend continuing.

Our latest Grattan report outlines a four-step plan to stop this trajectory and fix the private health insurance system. The first step is preventing insurers increasing premiums if they cannot demonstrate the policy offers value for money.

What’s the private health insurance ‘death spiral’?

An ageing population, increased use of health services, and rising health-care costs are driving up the benefits insurers have to pay out each year.

As pay-outs increase, insurers raise premiums, to recoup these costs.

Rising premiums make health insurance less affordable and less attractive — particularly to younger and healthier people.

Read more: How do you stop the youth exodus from private health insurance? Cut premiums for under-55s

As younger, healthier people drop their insurance, the insurance “risk pool” gets worse; people who hold insurance are older and more likely to use their benefits and use them to a greater value.

This increases the cost of premiums, younger people drop out, and the death spiral starts again.

What does the data say?

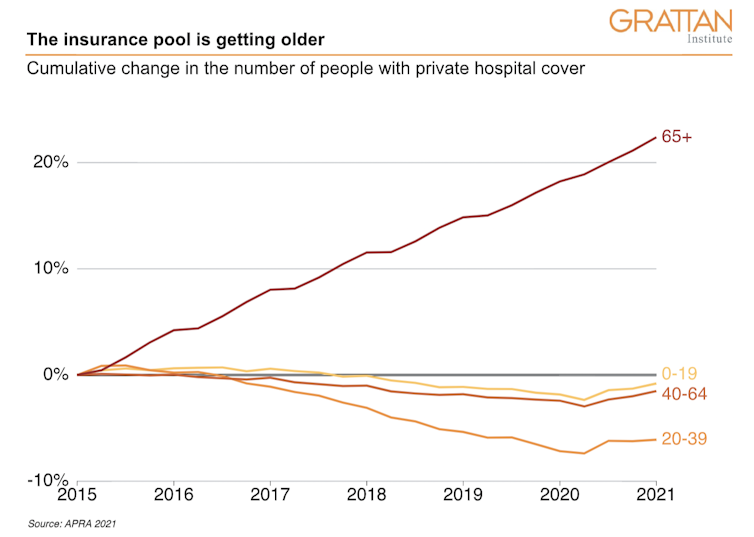

The chart shows the overall trends in private health insurance over the past six years.

Over this time period, the number of people with private health insurance over 65 — who are likely to draw on their health insurance, receiving more in benefit pay-outs than they pay in premiums — has increased dramatically.

At the same time, the numbers in all other age groups is declining, albeit with a slight uptick in the September quarter of 2020, possibly associated with people being allowed to defer premium payments during the COVID crisis.

The picture is particularly stark for 20 to 39-year-olds. People in this group make the pool of people insured less risky overall.

So far, policy tweaks have failed

In 2017 the federal government announced several rearrangements of private health insurance deckchairs to make the product more affordable or to encourage young people into insurance.

This included:

- simplified gold/silver/bronze/basic labelling of products

- increasing excesses from A$500 to $750 for singles, and double that for families. Premiums are lower for people who accept higher excesses to reduce premiums

- premium discounts from 2% for 29-year-olds to 10% for 18 to 25-year-olds.

Read more: Premiums up, rebates down, and a new tiered system – what the private health insurance changes mean

But these initiatives have failed to entice young people into private health insurance.

What are the solutions?

Our report proposes four key changes to:

1. Address premium increases, which are currently too great and too frequent.

Over the past 20 years, private health insurance premiums have grown faster than inflation, faster than health-specific inflation, and faster than wages. If people want to keep their same level of insurance, they have to fork out more and more.

Insurers that won’t or can’t offer their customers value for money should not be allowed to raise their premiums.

A new private health industry plan could reinforce the incentives for insurers to improve their claims ratios. This is the proportion of premium revenue returned to members in the form of benefits.

The health minister could also require funds to provide additional justification for a proposed increase if the proportion of their premiums returned to members is worse than the average claims ratio.

2. Reduce private hospital costs.

Unnecessarily long stays and examples of low- or no-value care are more common in private hospitals than in public ones. This drives up the cost of private hospital care.

A new private health industry plan should create incentives for private hospitals to become more efficient. One way to do this would be for insurers to pay private hospitals in a similar way to how government funds public hospitals. This would mean insurers pay private hospitals for the patients they treat, not for how long patients stay in hospital or the other services hospitals provide.

Improving private hospital efficiency and reducing low- or no-value care could reduce premiums by 5%.

3. Reduce out-of-pocket costs.

Out-of-pocket costs on medical bills are often in the hundreds of dollars, and sometimes in the thousands. In 2019-20, the average medical out-of-pocket cost was $544, and the average hospital out-of-pocket cost was $411.

Out-of-pocket costs are a major source of people’s dissatisfaction with private health insurance, and astonishingly high billing by a minority of doctors is a major cause of these costs.

Read more: Greedy doctors make private health insurance more painful – here’s a way to end bill shock

Comprehensive, public information on fees and costs would help. But even that is unlikely to significantly reduce the size and prevalence of out-of-pocket costs, because patients face an inherent power imbalance when dealing with doctors.

A new private health industry plan should include the structural reform required to reduce surprise out-of-pocket payments. This may come about through downward pressure on medical bills, or with more deals between doctors and insurers to bridge the gap.

4. Reduce the price private insurers pay for medical devices.

Surgically implanted medical devices include hip and knee replacement devices, cardiac stents and pacemakers. Currently, medical device manufacturers and importers, and private hospitals charge more than twice as much for these as public hospitals, a nice gravy train which they lobbied health minister Greg Hunt to retain.

This year’s budget revealed the minister backed down on a plan to reduce the cost of health insurance premiums by stopping medical device rorts. The budget announced yet another process of investigation and analysis, rather than making the tough decisions to end the excess charging, which would allow cuts in private health insurance premiums.

Stephen Duckett is director, Health Program, Grattan Institute

Anika Stobart is associate, Grattan Institute

This article was originally published at The Conversation