There’s a good chance your patients could be mistaken about which food chemicals are causing them grief

Overcoming a lifetime of food-related trauma, Mark slowly unpeeled a banana, gingerly sliced off a one-centimetre coin, popped the piece into his mouth, and swallowed.

His stomach heaved – but Mark was determined.

He forced the rest of the vile, pale-yellow breakfast down and left for work.

Mark (not his real name) was in the home stretch of a gruelling seven-month elimination diet to re-test his food intolerances.

As a child, Mark had been extremely sensitive to three common food chemicals: amines, salicylates and glutamate, which are found in most fruits and vegetables.

Food intolerances sometimes change over time, so Mark, aged 27, was embarking on a diagnostic elimination diet consisting largely of boiled eggs, porridge and rice.

The bland baseline diet would help pinpoint which food was causing acid reflux, gastrointestinal and neurological symptoms. Over the past few days, Mark had been testing his amines threshold by eating quite a bit of dark chocolate.

But it was the banana, which also contains amines, that pushed him over the limit.

“That afternoon, I actually remember standing in a colleague’s office with a Tupperware bowl in front of me trying to resolve a particular piece of work whilst I was throwing up,” Mark recalls. “Then I started to get quite severe neurological reactions,” he said. “I started really struggling with vision. It was as though I was capturing one frame per second. Like one of those old time films, where someone has recorded a film literally by rolling a thing through a machine and everything seems quite juttery.”

Mark’s hypersensitivity to light, sound and touch got progressively worse over the next two hours, by which point he knew he needed to get home.

“I remember leaning against the wall as I left to try to make sure that I didn’t fall over,” he said. When Mark got back to his apartment, he removed all his clothes, drew the blinds and switched off the lights, and stayed like that for the next two days.

“I remember being intensely uncomfortable,” he said. “Like I wanted to rip my own skin off. Even just the air prickling against my skin was unbearable. “I’m not meaning to be hyperbolic when I say if I had the ability to recognise that throwing myself off my balcony would have ended it then I probably would have done that. It was just torture.”

TIPPING POINTS

It’s estimated that around 5-20% of people have food intolerances, although less than 5% have severe reactions. Unlike food allergies, which are mediated by the immune system’s IgE antibodies, food intolerances occur in people with sensitive nerve endings.

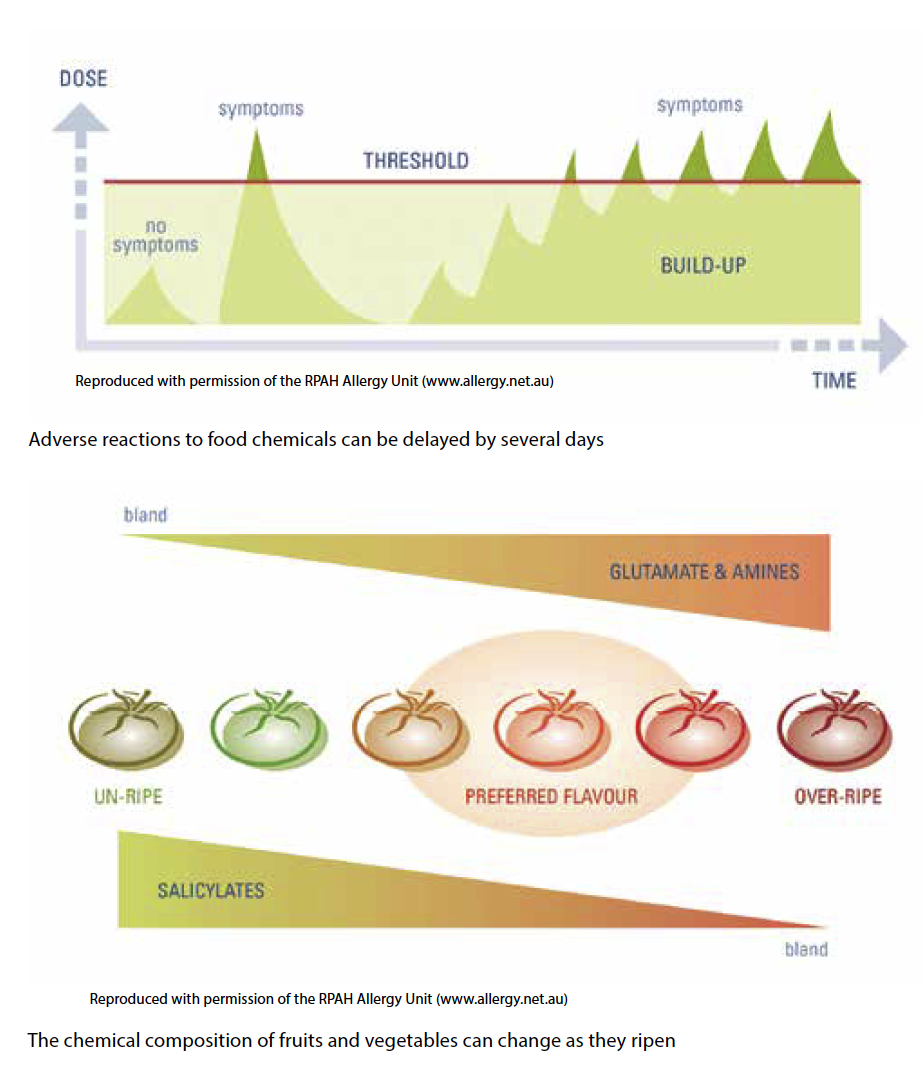

Allergic reactions to food happen immediately after eating, whereas people with food intolerances generally react to a build-up of food chemicals in their system over a few hours or days. The common analogy used is a bucket overflowing after hours under a dripping tap; it’s the final drop that pushes the water over the edge. Most people with food intolerances are sensitive to more than one chemical, but people such as Mark, who react badly to amines, salicylates and glutamate, are very rare. Mark is also lactose intolerant, which further restricts his diet.

“I am informed by my parents that I was throwing up breast milk at the age of two weeks,” he said. “Frankly, I’m glad my parents didn’t throw me off a bridge. It would have been quite understandable if they had, because apparently I just didn’t really sleep for the first two years of my life.”

Mark recently discovered that soy causes symptoms, too.

Most elimination diets take about two to six weeks to complete, with food challenges starting once symptoms subside. Mark’s symptoms didn’t settle for the first four months of the elimination diet because he was having so much soy milk. It was only when he cut out soy that all symptoms ceased and the challenges could begin.

Initially, Mark embarked on a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial, where each chemical was encapsulated in a pill. This was later followed by a food challenge trial to clarify what had appeared to be an adverse reaction to a placebo, but turned out to be a five-day delay to amines.

One pill (which Mark later found out contained acetylsalicylic acid) landed him in hospital.

About 12 hours after taking the challenge pills, Mark developed significant chest pain and found it harder and harder to breathe.

The hospital staff ran an ECG to confirm he wasn’t having a heart attack, and said he was probably just producing a lot of stomach acid.

“They gave me some antacids and gave me a drug called Pantoprazole, and that pulled me right back and I was OK after that,” Mark said.

ACIDIC, RICH, FLAVOURSOME AND WINDY

We’ve known since the 1970s that manipulating diets to exclude certain natural food chemicals, preservatives and additives can improve a range of symptoms in people with food intolerances, including urticaria, irritable bowl, migraines, and behavioural issues.

“Our understanding of food intolerance has not really changed over the years,” Dr Anne Swain, the head dietitian at Royal Prince Alfred Hospital Allergy Unit, told The Medical Republic.

The general public might not know the scientific names of the food chemicals that are causing them trouble, but the colloquial terms closely mirrored the science, Dr Swain said.

“The awareness in society is there. The words that people used to use in the past were the ‘acidy foods’, like tomatoes and citrus, which is really the salicylates,” she said.

“They’d use the ‘rich foods’ when they were talking about amines – you know, cheese, chocolate, bananas.”

Then there are the ‘flavoursome foods’, such as mushrooms, stock cubes, soy sauce, vegemite and flavoured noodles.

These contain either glutamate, an amino acid building block of all proteins found naturally in foods, or its salt, MSG (monosodium glutamate), which is used as an additive in savoury snack foods, soups, sauces and Asian cooking.

And the FODMAPs, fermentable sugars such as fructose, “that’s really what people used to call the ‘windy foods’” because they often caused bloating, abdominal discomfort, wind and diarrhoea Dr Swain said.

Most foods have at least one of these chemicals, and it’s not always easy to guess which foods have higher concentrations of each chemical, although flavour is a very good guide.

For example, iceberg lettuce has low concentrations of amines, salicylates and glutamate, but rocket has high levels of amines and salicylates, while spinach has very high levels of all three chemicals. Pears are low in amines, salicylates and glutamate, but high in fructose.

Cashews are a great choice for people with food sensitivities because they are low in amines, salicylates and glutamate, but most other nuts contain high levels of amines and salicylates. To make matters more complicated, the chemical composition of fruits and vegetables changes as they ripen. Hard, unripe tomatoes are packed full of salicylates, whereas soft, ripe tomatoes have less salicylate and are stuffed with glutamate and amines.

Amines are formed through the natural breakdown of proteins, so the amine concentration increases as beef, fish and cheese age.

Frozen, canned, salted, smoked, pickled or dried fish are so rich in amines and other food chemicals that people with food intolerances who eat them can have a marked reaction. Cooking can also affect the chemical content of foods, with browning, grilling or charring of meat increasing amine formation.

Resources such as The Royal Prince Alfred Hospital’s Elimination Diet Handbook ($22 from bit.ly/2DNnV35) assist patients to navigate the complexity by separating foods by low, moderate, high, and very high chemical content.

As a general rule, the more potent the flavour, the more chemicals in the food.

Fresh tomatoes have some amines, salicylates and glutamate, but the concentration is very high in tomato juice, soup, sauce and paste, for instance.

Other foods with high chemical content include (but are not limited to) ham, salami, avocado, chocolate, mushrooms, sausages, stock, mustard, mint, mayonnaise, soy sauce, red or white vinegar, wine, beer and anchovies.

People can reduce symptoms of food intolerance by swapping out some of these rich foods for chemical-light choices such as eggs, canola oil, margarine, chicken, leek, shallots, celery, potatoes, lamb, citric acid, salt, gin, whisky, fresh fish, garlic and chives.

“I’m not saying they can’t have these [high chemical foods] at all,” Dr Swain said. “I’m saying just don’t have truckloads of them.”

Limiting one’s intake of bothersome chemicals using the Handbook as a guide was safe even without the supervision of a dietitian, Dr Swain said.

“Good nutrition is about eating from the five food groups. So think about the old healthy diet pyramid. The five food groups, that’s the vertical, that’s good nutrition. The horizontal is variety. And all you are doing is bringing in the variety a little bit.” Not every patient with food intolerances needed to undergo a time-consuming elimination diet; the patients that chose this option generally had marked or severe symptoms, she said.

“For those that get the occasional symptoms here and there, they are just going to take the top off, get rid of the really concentrated forms like too much tomato, too much citrus, too much fruit juice. And that’s often all they need to do.”

MISATTRIBUTION

It’s human nature to want things to be easy and logical and have cause and effect be quite close together, but with food intolerance it doesn’t quite work like that.

People often misattribute their symptoms to the wrong food type for a number of reasons.

Firstly, food is complex. Meals are made up of lots of different elements and we eat several meals every day, which have each been prepared in different ways with a multitude of seasonings and garnishes that themselves contain a wealth of different ingredients.

Teasing out all these variables in a scientific way requires strict adherence to a punishing elimination diet and regimented record keeping. Unlike food allergies or coeliac disease, there are no diagnostic tests for food intolerance.

Secondly, people with food intolerances often do not react to food chemicals straight away.

“You may have a little bit of cheese, banana, juice, tomato, orange and then have the chocolate and then you get your headache,” Dr Swain said. “And what are you going to blame? The chocolate, because it’s the naughty but nice last food. You’re not going to think about the build-up.”

Thirdly, people’s food tolerance levels can change when they are stressed or ill, which adds noise into the data.

And, lastly, people often mistake correlation for causation.

“They’ll start to look for the common denominators, which is one of the reasons people blame wheat and milk a lot because they are commonly found in food,” Dr Swain said.

“Sugar is another one that they often implicate, but it’s rarely sugar. In fact, it’s usually not sugar but all the flavours, colours and preservatives in sugary foods.”

BROADER THE BETTER

Food intolerances are incredibly idiosyncratic, and every individual has slightly different triggers and thresholds.

The purpose of an elimination diet is to figure out what specific chemicals are causing the trouble, and then to gradually add as many foods as possible back into the patient’s diet. Unfortunately, pouring over food chemistry charts and manipulating each variable one by one to create a personalised diet is not as easy as jumping on the gluten-free bandwagon or giving up on dairy.

“People want to grab onto something that’s black and white and go, ‘This is it’,” Natasha Murray, a dietitian and spokesperson for Dietitians Association of Australia, said.

Often people feel a lot better when they make sweeping modifications to their diet, forgetting, of course, that they could just be drinking more water or eating more regularly, Ms Murray said.

That’s how fad diets get started. Dietitians strongly caution against diets that recommend cutting out entire food groups, even if these diets make people’s symptoms disappear.

“The Australian dietary guidelines recommend eating a variety of foods from all different groups,” Ms Murray said. “There is nothing wrong with dairy, there is nothing wrong with wheat, there is nothing wrong with fruits, there is nothing wrong with coconuts. Every food has its place in your diet.”

For people such as Mark, however, who get panicky just thinking about venturing out of their safe zone, many foods go in the too-hard basket.

“It’s a fear thing to some extent,” Mark told The Medical Republic. “It’s also just easier to stick to foods that you know are safe.”