Rates of influenza in Australia are at historically low levels as measures to combat COVID-19 could have lasting effects

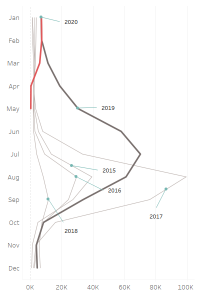

It’s been a whiplash year for influenza. In 2019, Australia had the highest number of influenza cases on record. But the last few months of this year have shown historically low levels.

Experts believe the low rates are probably thanks to measures taken to curb the spread of the SARS-CoV-2 virus which is causing chaos across the globe.

This raises the question: what does this mean for the future of influenza?

For Kim Sampson, CEO of the Immunisation Coalition, this year’s drop in influenza cases is “highly significant”.

“What it’s telling us is that these rules have been applied around protecting Australians from COVID-19 applies equally to other respiratory viruses,” he said.

The “dramatic” decline in influenza coincided with the introduction of social restrictions for coronavirus, Mr Sampson said, and similar trends have been seen in other countries, Hong Kong and Singapore for example.

We periodically have big influenza years and small ones, and this year had been shaping up to be a big one.

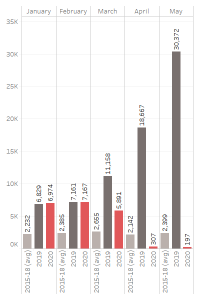

At its peak in February, Australia had more than 7100 laboratory-confirmed influenza cases.

But by April, when Australia had begun introducing measures such as social distancing, school closures, better hygiene and hand-washing and self-isolating when sick, the number of cases had dropped to 300 and by May there were fewer than 200 cases.

Compare that with last year when Australia experienced more than 300,000 cases and around 1000 deaths.

May 2019 saw more than 30,000 people were diagnosed with influenza – a figure far higher than the 2400 on average for May over the four years prior.

While we won’t know how many lives this has saved until the federal government’s end-of-year review, Mr Sampson said he was not aware of any flu deaths so far for 2020.

Moreover, we are seeing a drop off in other respiratory diseases, such as respiratory syncytial virus, or RSV, rhinovirus, and gut diseases such as gastroenteritis.

So what should we learn from this unexpected natural experiment?

“There’s a really important message in there, and that is that we can do a lot more to protect ourselves from some vaccine preventable disease or communicable diseases,” Mr Sampson said.

Associate Professor Paul Griffin, an infectious diseases physician and microbiologist at the University of Queensland agreed, saying that “I think we became a bit complacent with the flu”.

He believes it is important for us to adopt some of these changes when the threat of coronavirus fades. In particular, he would like to see people stay home when they are unwell.

“People think they’re doing the right thing by turning up to work and, even in pre-pandemic times, the additional burden and cost of people turning up when they’re unwell and passing things on to work colleagues is enormous,” Professor Griffith said .

It’s hard to know whether such a stark drop in flu cases will have a longer-term effect.

“I think at least for one or two years, we’ll see really modest levels of transmission while people are really mindful about washing their hands and staying away from people that are sick,” he said.

Given that a significant amount of influenza is imported from overseas, particularly in the off seasons, a government clamp-down on travel would also probably continue to have a big impact this season.

More people who have the flu are likely to have it confirmed in the laboratory too, thanks to COVID-19 nasopharyngeal swabs coincidentally picking it up.

This will hopefully mean the scientists monitoring influenza rates and strains have a better understanding of what types and amounts are in the community and can respond accordingly.

“So I think our level of flu control will be really good for a period of time while we’re able to respond like this,” Professor Griffin said. “But I’m just not sure how long that will last.”

To eradicate flu altogether would require a lockdown as strict, if not stricter than, at the peak of COVID-19, for a very long time, Professor Griffin, said, which was not a realistic or feasible approach.

“Having said that, if we keep up all these restrictions, and we do get some lasting behavioural change from what we’re seeing here, that, with influenza vaccination uptake increasing, could certainly have a really meaningful long-term impact,” he said.

However, changing human behaviour is one of the hardest things to do, explained social scientist Dr Holly Seale, at the University of NSW.

Yes, the general population may be more informed about infectious diseases and how viruses are spread than at any other point in history, but it’s unlikely that education alone will keep people washing their hands adequately, Dr Seale said, citing efforts to increase handwashing among medical staff.

“We know that having the knowledge is not necessary or sufficient to change your behaviour. We have been educating healthcare workers for a long, long time, and healthcare workers do an extremely great job at the roles they do, but we know that there are a range of reasons that they don’t wash their hands.”

What did lead to behaviour change was usually a combination of factors, such as somebody recommending the action, the person believing in the importance of the action and whether the action would hve a positive effect on their health, she said.

Dr Seale was doubtful that this pandemic would lead to lasting hand-hygiene improvements.

“Have past events radically changed our hand-hygiene behaviours? No, not really,” she asked. “We have had big flu seasons in the past five years or so, and we don’t see radical changes in behaviour.”

As people’s perception around the risk of coronavirus shifts, we are likely to see a drop off in the behaviours that helped quell the spread of viruses.

And while people in areas that have been hardest hit, or who have had the pandemic affect them more personally, may change their behaviour for the longer term, many people across Australia had very little or no direct interaction with sick people.

And behaviour change doesn’t only hinge on an individual’s intention.

For example, organisations have rapidly responded to the pandemic by introducing perspex glass in between cashiers and making hand sanitiser available. Such measures do little to impede the interaction between cashier and customer but does help protect the worker from a range of infectious diseases.

Dr Seale said that the decision to keep or discard these fixes could play a role in ongoing infection transmission.

And while individuals might now realise the benefits of staying at home when sick, if they don’t have sick leave or feel like they will be punished for doing so, widespread behaviour change would not be possible.

The pandemic, meanwhile, has certainly sparked interest in the flu vaccine, with more than seven million vaccines dispensed already this year. In contrast, only 4.5 million had been dispensed in the same period in 2018, Health Minister Greg Hunt said in late May .

Experts hope that one beneficial outcome from the pandemic is that the huge amount of resources being funnelled into a vaccine for COVID-19 will help also improve vaccine development for influenza.

Likewise, improvements in diagnostic testing, particularly testing that can be rapidly scaled up, and information sharing, are all processes that have been refined by the urgency of this pandemic. These things could improve our preparedness for the next pandemic, flu or otherwise.

It’s not all good news, however. Professor Griffin pointed out that a lot of the companies working on improving the flu vaccine or developing a new one have now diverted their attention towards developing a coronavirus vaccine.

“We will see a bit of a slowdown of the development of novel influenza vaccines for a few years to come,” he said. “That attention on influenza testing and treatment and vaccination has certainly slowed down .”

One factor that could have major implications is if a COVID-19 vaccine winds up bundled together with a flu vaccine.

This could increase the demand for the flu vaccine, keeping rates lower in subsequent years.

Regardless, scientists will be watching the influenza numbers closely as governments ease restrictions across the country.

In part, because influenza could be the “canary in the coalmine”, Mr Sampson said.

“We believe that what we might see is that as the restrictions are eased, we’ll see an increase in influenza,” Mr Sampson said. “And that will be a signal that COVID-19 is probably going to increase.”

The overall effects of the coronavirus are far too complex to figure out what the net outcome is. However, it is interesting to note that with only around 100 deaths from COVID-19, the corresponding drop in influenza deaths may have actually saved lives overall.

Of course, a lot can change in the next few months. Most worrying is that the currently low rate of influenza could lead to complacency.

“The worst thing will be if the flu rebounds,” Mr Sampson said. “If you are infected with influenza, it has a dramatic negative impact on your immune system. The last thing you want is a hit from COVID-19 to follow it, because that could be catastrophic.”