The outgoing director says the agency is getting better at its job. But the numbers say otherwise, never mind the distress and fear it causes.

PSR director Professor Julie Quinlivan’s departing statement in the agency’s quarterly update attempts to make a case for her five-year tenure at the watchdog being highly productive, even innovative.

“The Agency has grown to handle increasingly complex matters including implementation of the review of corporate practices and the expansion of reviews of medical specialists and other health professionals. The Agency regularly handles more than double the historical annual workload.

“In the 2021 Australian Public Service (APS) staff survey, PSR ranked 2nd of all 101 APS Departments and Agencies in overall scores and in staff innovation.

“I am confident I leave PSR in excellent shape…”

As if to underline her formal statement, in an interview last week with specialist media group the limbic on her tenure, she said quite a bit in defence of regular criticisms of the agency, stating openly that:

- the PSR has “really good procedural fairness measures” in place

- doctors are allowed “proper legal representation in PSR hearings”

- fairness has increased because the agency now looks at specialists and corporates, not just GPs

- the MBS isn’t really that complex to interpret

- 99.9% of doctors do the right thing and the agency is dealing with only a very small cohort of doctors who make mistakes or are doing the wrong thing

The PSR is supposed to decrease the relative incidence of fraudulent and mistaken (non-compliant) claims; increase education and awareness of common billing mistakes among doctors so that fewer mistakes are made; significantly lessen the taxpayer burden that mistakes or fraud are costing Medicare; and, through all this, improve patient care.

If you score Professor Quinlivan and the PSR on these key performance criteria, the numbers point to continuing and systemic failure of the agency.

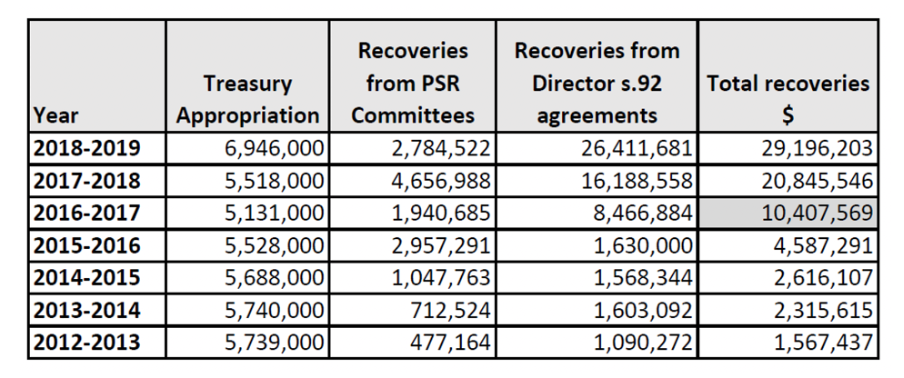

The only improved key performance indicator in Professor Quinlivan’s tenure is total recoveries, something that she didn’t highlight as she left. These improved by a seemingly spectacular six times from about $5 million to $30m during her reign, while the cost of running the agency has risen from $6m to $7m.

According to Medicare billing expert Dr Margaret Faux, if you put that recovery figure in the context of what she has calculated as the total leakage in the system due to non-compliant claims of somewhere between $1.2 billion and $3.6 billion, then the PSR could be capturing less than 1% of the total leakage.

In other words, in relative terms, recoveries are still so small that they remain meaningless compared with the total public monies being lost to a badly designed and run system.

Not even scratching the surface

Dr Faux, who wrote her PhD thesis on Medicare claiming and compliance, thinks the inability of the PSR to make any meaningful inroads into such a big figure probably points to some systemic issues with the whole Medicare billing paradigm, something that the PSR doesn’t address.

Surprisingly, Professor Quinlivan seems to admit up front in her the limbic interview that she isn’t entirely comfortable with how the PSR works either.

“Being a regulator is really difficult because you don’t set policy,” she says.

“Your job is simply to implement policy set by government and to follow the law. That’s the role. It isn’t to do what you want to do; you have to do what the law says.”

Having admitted this, Professor Quinlivan goes on to describe her most important key performance indicator in the role as court wins, not creating greater efficiencies through gradually educating doctors better on billing.

The limbic: Do you think the PSR has done a good job?

Professor Professor Quinlivan: I do actually. Historically, the PSR really only ever won about 50% of its Federal Court of Australia actions. Today, we are consistently winning all of them. That shows we have really good procedural fairness in place. Every single person appointed to a PSR panel receives annual training in procedural fairness as well as in how to ask questions and listen respectfully.

Asked what she thinks of the past five years of the PSR, Dr Faux says the agency prosecutes only a very small number of easily identifiable transgressions and as a result is “ineffective and delivers no value to the public”.

“What we have is a failed system catching only providers who are careless enough to become statistical outliers, billing a tiny handful of items.

“What we need is a fairer system designed to pull up the $7-8 billion per annum of current leakage, which is occurring right across the entire 6,000 item numbers and in numerous contexts.

“The PSR is not even scratching the surface.”

In the first 20 years of the agency’s existence, it didn’t even recover its operational costs while it got itself mired in litigation and bureaucracy, so in a sense, before Professor Quinlivan it wasn’t scratching anything either.

Notably Professor Quinlivan doesn’t point to her recoveries performance under her tenure as a highlight. You can imagine, however, that her bosses would be pleased that she made the agency at least start paying for itself, and more.

Is there still some upside in such an increase in recoveries in terms of more than money for the government, though?

There would be, if all this activity ended up changing the pattern of behaviour of doctors and therefore resulted in the overall rate of leakage reducing meaningfully over time.

But Dr Faux points out, alarmingly, that this isn’t happening at all. In fact, in relative terms things look like they might be getting worse.

She points to the figures over the years, the usual suspect item numbers the agency makes its recoveries from, and argues that if the PSR is making more recoveries on the same items year on year, then there is obviously no behaviour change, and probably no effective education going on.

So, doctors aren’t learning, or getting any better at interpreting the MBS schedule, and the small cohort of doctors who are terrorised by the PSR each year keep doing the same thing wrong as those who were stung in previous years.

Dr Faux says we are wasting most of the money we spend on the PSR – and worse, possibly decreasing patient care standards by scaring our entire doctor community each year into being overly conservative via horror stories of what happens if they do get caught in the PSR net.

“It is difficult to see how the PSR facilitates justice or benefits medical practitioners or their taxpaying patients, in view of demonstrably poor financial and deterrent results,” Dr Faux says.

“While precise figures are difficult to extract from the Australian National Audit Office (ANAO), PSR and DOH reports for the same period, it appears that total MBS recoveries from combined PSR and DOH activities (noting this excludes PBS recoveries) in the 2018-2019 fiscal year totalled approximately $38 million, or 1-3% of the estimated leakage.

“This suggests that more than 97% of non-compliant Medicare claims are never recovered. Compliance arrangements therefore appear to be weak and ineffective, and the government is unlikely to be meeting the required standard of ‘proper’ use and management of public money under the Public Governance and Accountability Act.”

Dr Faux points out that Professor Quinlivan has emphasised publicly that she is mainly focused on clinical records, which can only ever provide a partial indication of a compliant bill, because the actual item number may have been altered by a third party – Dr Faux’s PhD research showed instances where this has happened.

The problem with this approach is that an honest, hard-working doctor will be subject to the same fate as a dishonest colleague who has the time to deliberately abuse Medicare by auto-filling the clinical record with sufficient “notes” to have the PSR believe item requirements were met, even if they were not.

“The honest medical practitioner may have actually provided all services billed with a high level of clinical input and care but be found non-compliant due to poor notes, whereas a dishonest MP may pass PSR scrutiny with poor care but good fake notes,” says Dr Faux.

Procedural unfairness

The issues with PSR go way beyond the numbers, though.

Professor Quinlivan tells the limbic that the PSR has “really good procedural fairness measures in place” and that it’s not true doctors aren’t allowed proper legal representation in PSR hearings. On the contrary, Dr Faux says the PSR legislation does not permit full legal representation – a doctor is allowed to have their lawyer present, but the lawyer cannot speak for you or cross-examine committee members or intervene in any way on behalf of the doctor.

“The Director is either being deliberately misleading in her comments in this regard or is demonstrating her low levels of legal literacy around what constitutes full legal representation in contested legal proceedings,” Dr Faux says.

She is also critical of the secrecy around committee proceedings, which leaves a black hole where legal predecent should be and prevents doctors from learning from each others’ mistakes.

“If the PSR is so confident about its high standards of natural justice, then it should have no concern about opening up the PSR process to full public scrutiny and allowing the public and journalists into hearings, and also repealing section 106ZR, which is the gag clause,” Dr Faux says. “If they have nothing to hide, then they should agree to implement both of these measures.”

She says that the processes are so secretive that it’s not possible for anyone to understand just how “intimidating, threatening and coercing”, they might be for GPs, and whether “medical practitioners are being bullied into entering section 92 agreements, forced into false confessions of guilt while under duress, considering this option a prudent risk-mitigation strategy rather than being a genuine admission of wrongdoing”.

In her thesis, she states that “precedent is a cornerstone of our legal system that ensures everyone is treated fairly and equally before the law and after 25 years of operation [of the PSR], it is not unreasonable to think that a body of precedent might have been developed to assist medical practitioners to know how to bill correctly. Unfortunately, this is nowhere evident. Instead, the same issues are reported repeatedly, with the PSR making the same findings in relation to the same small handful of item numbers.”

Professor Quinlivan also tells the limbic that the “unusual powers” of the agency have been exaggerated: “Well there is a lot of misinformation out there about how we operate and claims that we have unusual powers. In fact virtually every regulator in Australia can require relevant documents and for the PSR that happens to be medical records. So that is not an unusual power.”

Maybe not, but this is: unlike any normal court, the PSR can find a few instances of what it deems inappropriate billing and punish the practitioner for a great many more billings that it has never looked at, but which it just infers were also inappropriate. This is called extrapolation.

When the investigator/prosecutor finds $9000 worth of incorrect billing and you’re made to repay $900,000 – that’s pretty unusual.

Confused and confusing

Then there’s the complexity and sheer obscurity of Medicare. Dr Faux’s thesis details how unwieldy and complex the MBS has become as a payments methodology, including a plethora of examples of how the complexity, combined with regular changes to items in the schedule, can easily trap unsuspecting doctors into billing incorrectly.

But in the interview with the limbic, Professor Quinlivan outlines an argument that the MBS is actually pretty simple to interpret, especially for GPs:

The limbic: How do you respond to the criticism that Medicare has become more complex though. It’s been argued that most doctors are at risk of non-compliance, even with the best intentions in the world.

Professor Quinlivan: My answer to that is that I’m a specialist and I see patients and I bill Medicare. Yes, there’s over 5,000 items on the MBS, but I really only bill about 15 of them. Reviewing GPs, we see the same 10 items over and over again plus their telehealth equivalents. And when we look at cases it is very rare that the concern is that someone has misread the item number. Overwhelmingly, the concern is that the service wasn’t performed or that the clinical record was really poor or that the management was inadequate.

If you flip through Dr Faux’s nearly 500-page PhD thesis, it’s pretty difficult to reconcile the detailed examples of complexity she outlines in the system, and mistakes being made, with Professor Quinlivan’s position that the MBS isn’t that hard to interpret.

The thesis includes some figures on the PSR treatment of specialists that don’t gel with Professor Quinlivan’s other outgoing comment that the PSR is somehow getting fairer because it now targets specialists as well as GPs, and that its remit includes GP corporates.

“The new Director has attributed her success to a greater focus on higher-paying specialist services, though a review of available monthly Director’s updates suggests this may be misleading,” Dr Faux writes.

“In the 2017-2018 financial year, $5,340,000 (33%) related to agreements with specialists out of a reported total of $16,188,558. In the following year, agreements with specialists totalled just $2,550,000 (9.6%) out of a reported total of $26,411,681.

“General practitioners have always been the principal target for the PSR. This is largely attributable to the fact that GPs are easier to target because they receive funding almost solely from Medicare and bill high volumes of time-based services.

“Specialists, on the other hand, bill fewer time-based services and their reimbursement streams are complex as we have seen, sourced from mixed public and private funding arrangements. The complexity of these arrangements makes specialist billing harder to investigate and prosecute.”

Dr Faux’s research is fundamentally challenging nearly every aspect of how the PSR is operating, and even the validity of its reporting.

Professor Quinlivan told the limbic that “99.9% of practitioners are doing the right thing, but the sad reality is there are a small number who aren’t and who need to be nudged back into the herd”.

Dr Faux’s research suggests that, as a result of the complexity of the MBS, and how it is managed, that 0.01% figure being quoted by Professor Quinlivan is more like 5-15%, and that most of these doctors are more confused than fraudulent.

That’s a lot of innocent doctors who are put through the wringer for a lousy $30m a year.