Storage, safety, strains and more.

The Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA) yesterday announced it has provisionally approved AstraZeneca’s COVID vaccine for use in Australia.

The approval applies to people over 18, including adults older than 65. The recommended interval between the two doses is 12 weeks, but the second dose can be administered a minimum of four weeks after the first.

We now have two vaccines provisionally approved, which is welcome news for Australia’s vaccine rollout. Vaccinations with the Pfizer shot are set to begin next week, and we should see inoculation with the AstraZeneca vaccine start some time in March.

Here are five things to know about the AstraZeneca vaccine.

1. Storage and distribution

The Oxford/AstraZeneca vaccine, also known as ChAdOx1 nCoV-19, or AZD1222, is a viral vector vaccine. Scientists used an adenovirus, originally derived from chimpanzees, and modified it with the aim of training the immune system to mount a strong response against SARS-CoV-2 (the virus that causes COVID-19).

One key characteristic of this vaccine is that it can be stored at 2-8? (so, in a normal fridge). This is distinct from some of the other COVID-19 vaccines — such as Pfizer’s mRNA vaccine — which must be stored at ultra-cold temperatures. So the AstraZeneca vaccine can be widely distributed with relative ease.

Additionally, AstraZeneca has multiple supply chains. Around the world they have multiple manufacturing sites, partners from whom to source ingredients, and distributors who can deploy the vaccine. These partnerships will accelerate production and distribution.

At this stage, the AstraZeneca vaccine will be the only locally available vaccine manufactured in Australia. Biotechnology company CSL has been working to upgrade its facilities so it can produce the vaccine locally at scale. It expects up to two million doses will be available by the end of March.

2. Safety and efficacy in people over 65

Phase 2 human trials tested safety and immune responses of the AstraZeneca vaccine, including in people over 65. The vaccine was found to be safe, showing just some mild and moderate reactions, and it induced similar immune responses across age groups.

Although the subsequent phase 3 trials included much larger numbers of people, they didn’t include as many older people as trials for some of the other vaccines. So researchers couldn’t confidently assess efficacy in this group at the time. Studies are ongoing, and there’s still some uncertainty about the vaccine’s efficacy in older people.

There are no specific safety concerns (especially based on overseas data) and the vaccine induces good immune responses, which is a positive indicator it could be effective in the elderly population. Therefore, the TGA has ruled the vaccine should be administered to elderly people “on a case-by-case basis” where the benefits outweigh the possible risks.

The person, their family and medical professionals might make the decision not to vaccinate if, say, the person is very elderly and frail, or has multiple medical conditions.

3. Timing of doses

In initial studies, the vaccine’s efficacy was 62% with two standard doses. However, there was some variability depending on the dosage and timing.

Since then, scientists have asked questions about the optimal dose and interval. A preprint manuscript in The Lancet shows the vaccine demonstrated 82.4% efficacy after two standard doses three months apart. The efficacy was lower if the doses were closer together: 54.9% if the interval was less than six weeks.

Although this data is yet to be peer-reviewed, it suggests the timing between doses is a key factor in this vaccine’s efficacy. The TGA has reflected this in its advice.

But will a person be protected already after one immunisation, while waiting for the second boosting jab? The preprint study shows the vaccine has 76% efficacy after a single dose, when assessed over the first 90 days after vaccination.

4. Protection against different strains

As viruses mutate and give rise to new variants, this can affect how well certain vaccines work against them.

We’ve seen this with the B.1.351 variant of SARS-CoV-2, originally identified in South Africa. Following a multi-centre clinical trial in South Africa, researchers concluded two doses of the AstraZeneca vaccine had minimal efficacy in mild to moderate COVID-19 cases, specifically due to the B.1.351 variant.

There’s still hope the vaccine will be effective against more severe cases of COVID-19. But South Africa has halted the rollout of the AstraZeneca vaccine for now.

The news is looking better for the UK strain, B.1.1.7. In a phase 2/3 clinical trial in the UK, researchers concluded the AstraZeneca vaccine had an efficacy against the B.1.1.7 variant similar to that of other variants — 74.6% compared with 84%. It’s important to note this study is also a preprint, so it hasn’t yet received the same scrutiny as other published research.

Interestingly, both the UK and South African variants have the same mutation — the N501Y mutation — but the south African variant has an additional mutation, E484K. Research shows this mutation contributes to the virus evading antibodies from COVID-19 patients against SARS-CoV-2.

5. Can it reduce transmission as well as disease?

This question has been asked of all COVID-19 vaccines, and emerging data for the AstraZeneca vaccine is encouraging. The Lancet preprint we mentioned earlier has shown this vaccine may block transmission after a single dose.

The researchers derived this data by taking weekly nose swabs from both symptomatic and asymptomatic cases and testing for the presence of the virus. (If a person has virus in their nose and are breathing it out, they’re more likely to infect someone else.) They observed a 67% fall in swabs positive for the virus after one immunisation.

In a separate preprint, people who received the AstraZeneca vaccine (as opposed to the placebo) and were swab positive showed reduced periods of viral shedding, which could also have a positive impact on transmission of disease.

This data suggests the AstraZeneca vaccine also has potential to substantially affect virus transmission, by reducing the number of highly infectious people in a population.

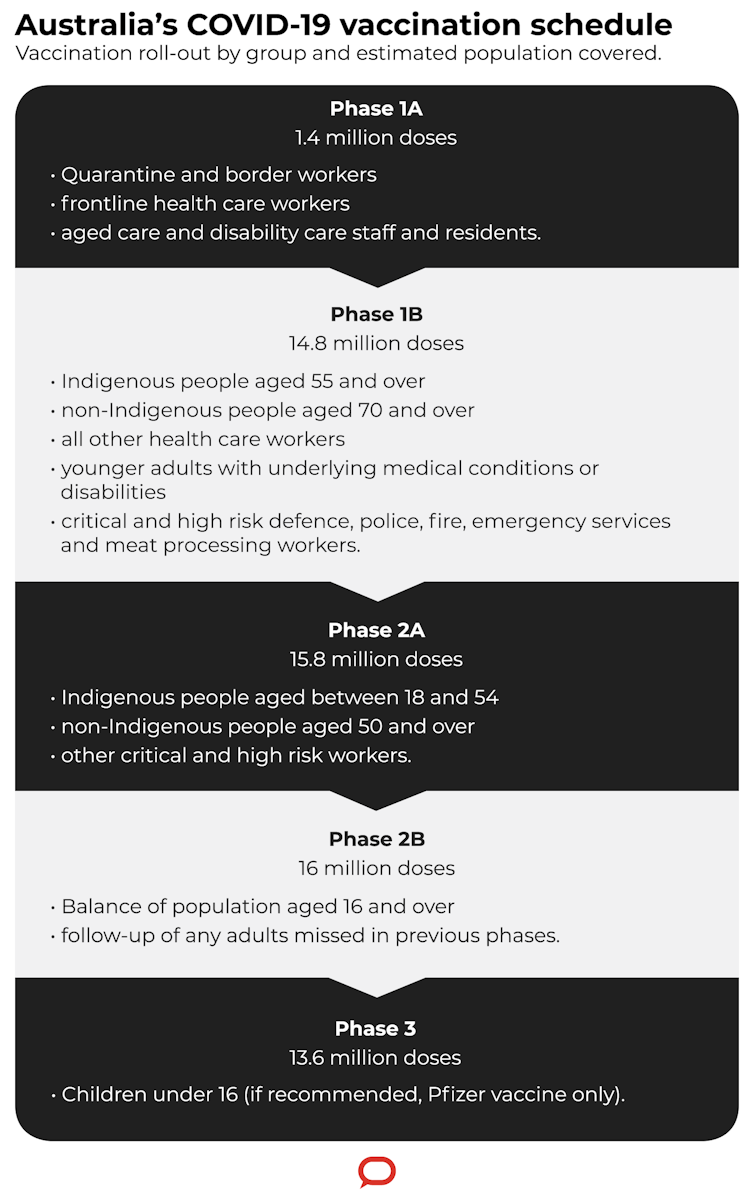

Read more: Australia must vaccinate 200,000 adults a day to meet October target: new modelling

Kirsty Wilson is a postdoctoral research fellow, RMIT University

Jennifer Boer is a postdoctoral research fellow, RMIT University

Magdalena Plebanski is professor of immunology, RMIT University

This article was originally published at The Conversation