Medical AI isn’t going to take your job, but it will change it, and if we don't approach it more professionally from a patient safety perspective, we may end up with some very serious and unnecessary stuff ups

If you’ve been watching the ABC in the last week you could be excused for starting to feel a little nervous about your future as a doctor if artificial intelligence (AI) starts to take on in the manner their reporters are suggesting it might.

On one night, they suggested that if you’re male and in a trade or profession – they didn’t delineate which sector of either – two thirds of those jobs will be done by computers within the decade and you stood a great chance of being unemployable in the not too distant future. Thanks ABC.

The situation isn’t helped by a string of consulting firm media stars appearing adding to the hype. And voodoo demographer Bernard Salt, with predictions of an ageing population creating a healthcare Armageddon.

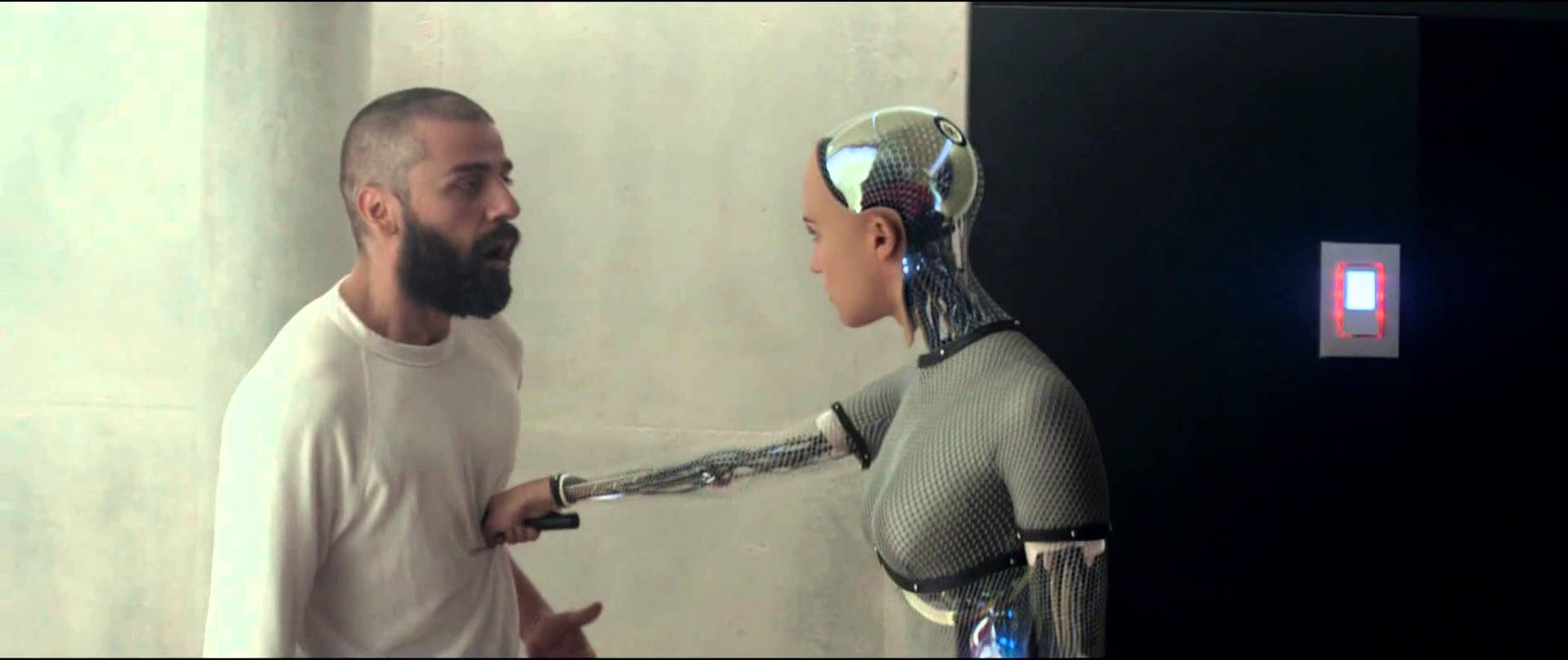

Add to all this Hollywood’s long obsession with machine (AI) versus humanity – The Matrix, Terminator, Blade Runner, iRobot, Westworld, and more recently, the tantalisingly edgy Ex Machina – and you could be forgiven for starting to believe some of the scaremongering.

Gordon Gekko famously said, “greed is good”. Today, surely, he would add “fear is good, too”.

Why, all of a sudden do we have the ABC, and the likes of rock star entrepreneur Elon Musk, suggesting the movie Ex Machina is but a new generation of computer chip away?

Business is the likely culprit.

Disruption, particularly AI-centred disruption, is becoming very big business. And healthcare is firmly in the sights of the major consulting firms and technology companies, because they are the purveyors of the solution – transformation, the answer to disruption.

To be fair, transformation is real. Technology is creating massive efficiency changes for all manner of businesses and activities, healthcare included. Processing power and “connectivity” via the “cloud” do bring the potential for massive efficiencies.

The business opportunity for helping people through these changes is huge.

But it’s blurring our vision.

AI is far from a new phenomenon. It’s being growing on us for a long time. Sure, if you stepped into a time machine in 1997 and hit the 20 years forward button you might step out and be a tad shocked at some of the things computers do: GPS navigation, search results just for you, friends for business and fun, just for you again, Siri and Alexa to assist you through your day, Spotify for music and Amazon for book recommendations, driverless cars, all the way through to some fairly important medical diagnostic calls, particularly in imaging diagnostics. And even diagnostic decisions and drug prescribing being done with very little human intervention.

Live GPS navigation seems awfully like Dick Tracy to me still. It’s been a lot of change in a very short amount of time.

But who has flamed out with fear and anxiety at the changes as they occurred to us all in this period? No-one really. It’s been fast and iterative, sure. But so iterative, we’ve sort of not noticed how much change we’ve all managed already. Pat yourself on the back. You’re pretty resilient. AI in one form or another has been around us and growing on us for ages. Today it’s getting pervasive and faster, maybe. But that’s OK.

“Siri. Get me some tickets to Midnight Oil in Rockhampton, please”. What’s the drama?

The drama isn’t that you’re going to lose jobs as medical professionals, or that machines will take over. Of all the professions, healthcare is one of the safest. In the end, it’s about care. And care, in all it’s detailed forms, isn’t easy to replicate on machines.

The most immediate impact of AI in medicine will be felt in diagnosis. That’s already apparent in radiology. But as Professor Enrico Coiera, Director of the Centre for Health Informatics at Macquarie University, says: “Diagnosis is just one day in the life of a patient’s healthcare journey. Everything that follows diagnosis makes up the majority of healthcare, so healthcare professionals haven’t got much to worry about.

“Healthcare won’t run out of jobs, because there is such a huge, unmet need for care. If we were to cure the top 10 diseases, we would then get to focus on the next 10, and so on.”

Professor Coiera sees the efficiencies inherent in medical AI as helping the problem of this unmet need.

But he is also worried that between the business of technology, the desire for speed to solve efficiency issues in the face of cost pressures in health, and the iterative nature of the introduction of AI into medical workflows, we are missing something vital.

“A lot of decisions in healthcare are going to be shaped by input from algorithms and while that is overall a good thing, we need to understand much better in what circumstances it will also be a problem. We need to be very clear about the framework in which we operate when we’ve made that conscious decision to hand over part of the care to an algorithm,” Professor Coiera said.

He warns that often we are introducing AI into medical processes without clear evidence of how we should be working with that technology, or without providing proper training to the healthcare professionals.

A simple example he cites is computer-based prescription writing, which is now becoming widespread.

“When you prescribe as an unaided human there are a set of errors you will make, and bringing in a computer can help to significantly reduce those errors. The issue is that using a computer introduces new types of errors, and we aren’t teaching people how to use the technology to manage these new types of error,” Professor Coiera said.

He cites the recent example of a rural GP whose prescribing error led to the death of a patient. The GP’s defence was “the computer didn’t tell me it was wrong.”

“That’s automation bias”, says Professor Coiera, who believes that computers aside, all clinicians need to be trained in the safe use of an electronic medical record, given how pervasive this technology is starting to become.

In a recent blog on the BMJ, Professor Coiera said: “ Like any technology, AI must be designed and built to safety standards that ensure it is fit for purpose and operates as intended.”

He also said: “Humans should recognise that their own performance is altered when working with AI … If humans are responsible for an outcome, they should be obliged to remain vigilant, even after they have delegated tasks to AI.”

Professor Coiera remains a very strong AI advocate, maintaining that its potential to increase efficiencies in an over-stretched healthcare systems is enormous. But he is also worried that the evidence for safety around the introduction of AI into medicine remains mostly slim, and that regulators rarely if ever get a look in when something iterative occurs inside existing automated systems.

“In aviation, if you develop a new model of aeroplane you have to meet stringent testing and accreditation guidelines before it can be used for the public. We don’t say, ‘oh, aeroplanes are a great idea overall, so new aeroplanes are OK to go’,” he said.

“There is currently no safety body that can oversee or accredit any of these medical AI technologies, and we generally don’t teach people to be safe users of the technology. We keep on unleashing new genies and we need to keep ahead of it.”

Professor Enrico Coiera is a keynote speaker at the Wild Health Summit on October 16 in Sydney. He will also be on the Q&A panel of the same meeting which will be asked how we meet the challenges of allowing the rapid introduction of AI into medicine while keeping the technology safe for patients. CLICK HERE to see checkout the other sessions at this important one day summit and use the promo code WILDTMR for a 20% discount on your ticket.