The scapegoat takes nasty feelings, actions and failures on its small head, and is led into the wilderness where no one has to look at it.

The term “scapegoat” is an ancient one, referring to a biblical story, but also turns up in other ancient communities and other texts.

“Then Aaron shall lay both his hands on the head of the live goat, and confess over it all the iniquities of the people of Israel, and all their transgressions, all their sins, putting them on the head of the goat, and sending it away into the wilderness by means of someone designated for the task. The goat shall bear on itself all their iniquities to a barren region; and the goat shall be set free in the wilderness.”

— Leviticus 16:21–22, New Revised Standard Version

It is important that the goat is led into the wilderness and then abandoned. It is not a choice, or an option for the goat. We GPs should pay attention.

Australia’s over-arching mental health strategy, the National Mental Health Plan, is created at a Commonwealth level to drive the mission of mental health care across the country. It relies on a safety net. After all the shiny services have cared for the patients they choose, it is the GPs who take the remainder. Because “the remainder” are defined by everyone except the GPs, many patients are failed by this system. GPs accept patients that cannot and should not be cared for in a primary care setting. Simply because they are rejected from everywhere else.

Interestingly, the front cover of the National Mental Health plan titles the work “Prevention Compassion Care” with no punctuation. Although undoubtedly, the authors meant us to read “prevention, compassion and care”, I think it is easy to read into this statement what is actually happening.

By fracturing mental health services into multiple parts that do not intersect, and driving engagement in e-mental health strategies that have no therapeutic relationships within them, are we not, in fact, driving the prevention OF compassion and care? We are certainly not funding the longitudinal, deep relationships we GPs have with our patients despite the evidence that therapeutic relationships improve outcomes.

Because it is inevitable GPs will fail to help the patients no-one else can treat, we become convenient scapegoats for the failures of the system. We too live in a comparatively barren region, struggling to access the resources to provide good care.

The Australian Health System

Our constitution sets up fertile ground for resource, cost and responsibility shifting, all of which contribute to inefficiencies and dangerous clinical access gaps. Our commonwealth is responsible for primary and aged care while our states take responsibility for other health services, such as hospitals, community health centres, outpatient clinics and other services they feel are necessary to meet their own health goals.

Our commonwealth leaders essentially contract the states to perform these services, by funding them with taxes, and work together at the Commonwealth Organisation of Australian Governments (COAG) meetings to negotiate their roles, strategies and agendas, as well as their roles in the shared marketplace of Australian consumers.

Private hospitals are funded by insurance companies, patient contributions and federal funding to individual practitioners. We also have non-government organisations that receive government grants from state and federal governments, as well as philanthropic funding. Private practitioners (including general practitioners) receive funding from the federal government through its Medicare Benefits Schedule, and also through patient contributions.

However, our government has recognised there is political cache in supporting “free” services in general practice, leading many Australians to expect GPs to not raise a co-payment. They have also systematically frozen Medicare rebates to GPs, meaning general practice is becoming less and less financially viable.

Our commonwealth and state governments control general practice not only through finance, but also through regulation, training (partly funded by the commonwealth) and public health campaigns marketed directly to consumers. they also have control over consumables, such as therapeutic goods and their funding, and supply other resources such as immunisations.

Health for all?

As a GP, my role is to provide unreferred services to all Australians, across all areas of health. I am tasked with coordinating care, and in many cases, I provide the referrals into other systems. In mental health, however, the situation is more complex.

Compared with other areas of practice, in mental health I have less access to specialist doctors. There is a critical shortage of psychiatrists in Australia, and the relationships between GPs and psychiatrists is much less collaborative than in any other discipline, probably because of this scarcity. Mental health services are staffed predominantly with other clinicians (psychologists, nurses, occupational therapists etc) who do not necessarily see the GP as part of their team. The poor communication between the mental health teams and general practice is entrenched, and profoundly dangerous. The system itself is a mosaic of commonwealth, state and NGO initiatives that are poorly coordinated, leaving the consumer (and the GP) bewildered about how and where to access care. The majority of my referrals into these multiple systems are rejected.

My unique skills are in generalism, the ability to work across systems in a patient centric way. I also work across the health promotion continuum, in primary, secondary and tertiary health promotion, in screening, reducing risk and treating complex mental health needs. I know my patients well, and I am in their community, so I am accessible, affordable and (usually) culturally fit for purpose.

I can choose not to see patients, but the commonwealth relies on my moral discomfort to ensure all patients are seen. Despite systematic defunding of general practice, this inherent altruism is the bedrock of universal health care. GPs as a group have a professional ethic of making sure each patient has access to care, and this usually means accepting care for most patients (and referring some to other GP colleagues if we cannot accommodate their needs).

GPs as scapegoats and the illusion of equity

Which brings me to my role in the system. It is becoming increasingly obvious to me that my role is to create the illusion of “Health for All” (1) by receiving patients who are likely to fail to meet organisational objectives in other systems, or pose too high a risk, or are too financially costly. Of course, my outcomes with these patients are likely to be poor, because I do not have a multidisciplinary team, a hospital bed or a case manager, but I am in the industry that provides a “safety net” for the patients who are not seen as worthy to receive other services, or cannot afford them.

GPs fill a politically important role, supporting the “Health for All” vision. I am economically cheap and as part of a series of small businesses, I lack a unified voice. I am also ideologically committed to patient care. I enable the other parts of the system to meet their internal strategic objectives, while failing to meet the overall mission. Bluntly, I take the patients who are too expensive, too marginalised, too poor, too difficult or too likely to fail to meet organisational targets. I am sure these decisions are not deliberate, but the economic and political drivers in the system make this behaviour likely.

In turn, it is difficult to understand what I do, because the patients who are easy to describe, and have readily understandable and measurable outcomes, are able to be accommodated somewhere else. This means I am a sitting duck for other people’s assumptions.

Apparently, I also have a bimodal role. I am seen as too incompetent, undertrained and conflicted to make a simple mental health diagnosis, according to the social services departments who manage the disability support pension. AT THE SAME TIME I am in an “ideal position to” manage the most complex patients in the system. This enables governments to ask me to take on the most difficult patients, but avoid resourcing me to do so.

In other words, the GPs are the scapegoats of the mental health system. This allows governments, hospitals and communities to shift blame. “If only GPs were more capable, educated, equitable, spent more time, had more empathy, were more patient centred, bulk-billed, etc,” they say, “we would be able to cope with OUR mental health load”.

I have been wondering why the idea of segments in health care has been uncomfortable and it has become clear in mental health that enables exclusion of the most needy, desperate and marginalised patients in the system, to the benefit of the institutions that are tasked to meet their needs.

We are also data poor. It is unfortunate that the Commonwealth defunded BEACH, (3) our long standing continuous study of GP activity, so we have little understanding of GP activity at a granular level. This absence of data means general practice work remains invisible in policy.

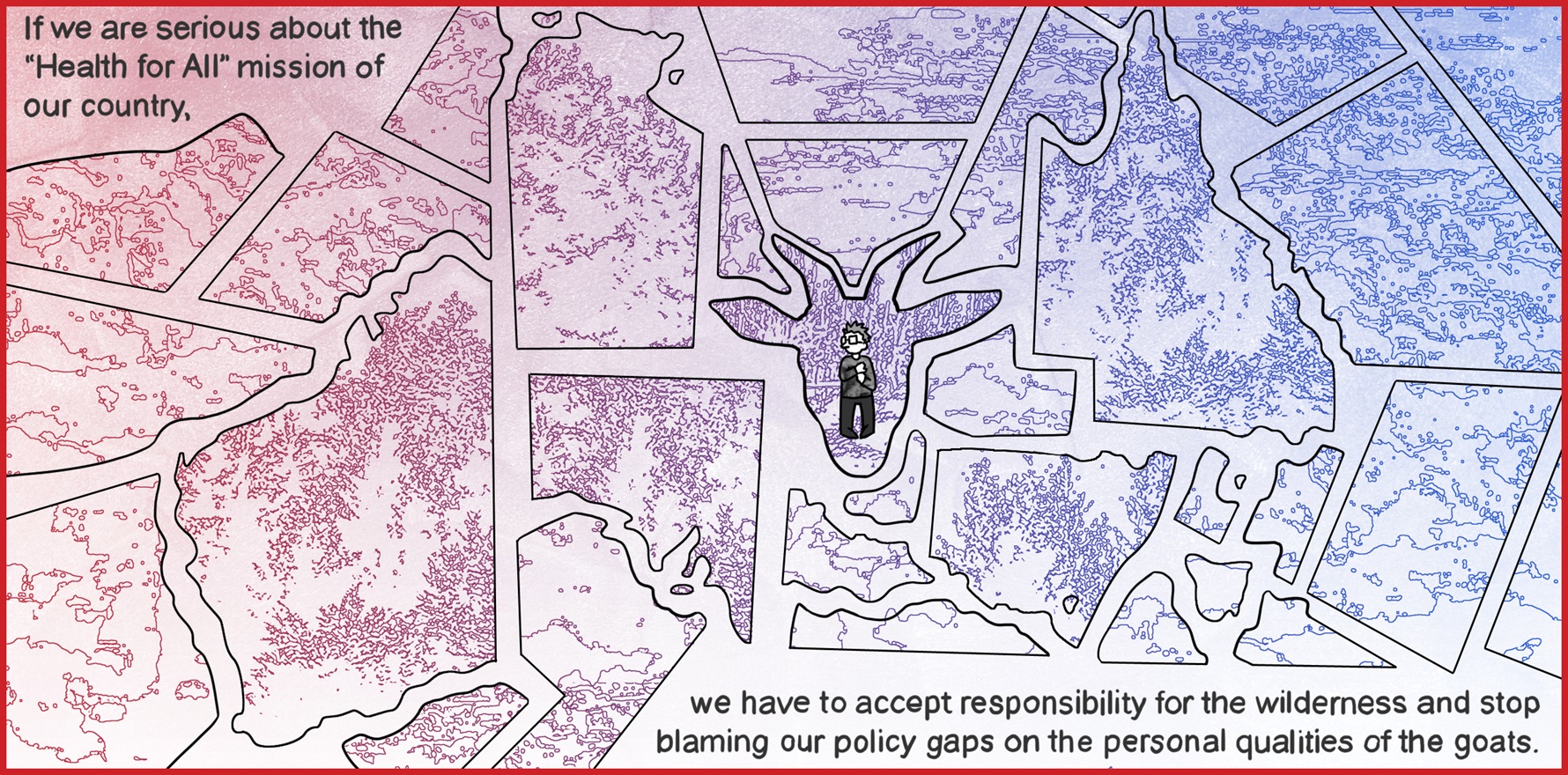

If we are serious about the “Health for All” mission of our country, we need to consider the outcomes of all Australians with mental health issues, not only the ones accepted by organisations that are funded to receive, treat and evaluate outcomes for certain segments of the community. We have to accept responsibility for the wilderness and stop blaming our policy gaps on the personal qualities of the goats.

References

- Department of Health. The Fifth National Mental Health and Suicide Prevention Plan. Canberra; 2017.

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. National Survey of Mental Health and Well-being: Summary of Results. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia; 2007.

- Britt H, Miller G. BEACH program update. Australian family physician. 2015;44(6):411.