A series of papers warns against overmedicalising this inevitable life stage and says women primarily need to be listened to and informed.

A series of papers in the Lancet timed for International Women’s Day say menopause is overmedicalised thanks to its commercial potential, and recommend an empowerment model – defined by the WHO as “an active process of gaining knowledge, confidence, and self-determination to self-manage health and make informed decisions about care”.

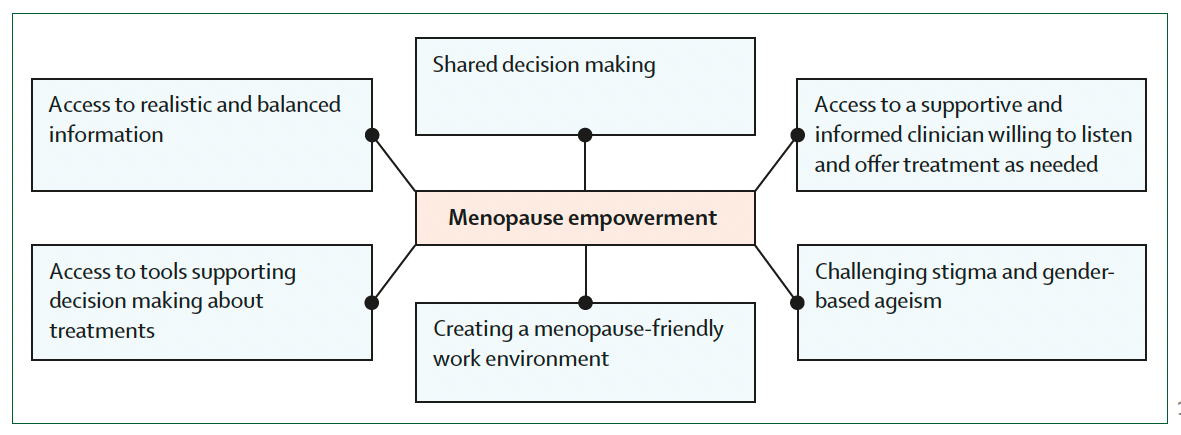

The first paper (pdfs of all four are here) describes the symptoms of menopause and evidence for treatment, noting cultural differences and the effect of stigma and ageism, and proposes an overall direction for management based on these key messages:

- Most women navigate menopause without the need for medical treatments

- Over-medicalisation of menopause can lead to disempowerment and over-treatment

- New tools are available to support the empowerment of women to navigate the menopause transition

- Empowerment is likely to confer benefits for women across socioeconomic and geographical locations, health services, and economies

From Hickey et al. An empowerment model for managing menopause, Lancet, 5 March 2024

The second paper is on the specific management of early menopause, the third looks at mental health during menopause and the fourth is on managing menopause after cancer. All four papers are systematic reviews.

In the first paper, the authors – an international group led by Professor Martha Hickey from the Royal Women’s Hospital in Melbourne – say the disease model of menopause as a hormone deficiency is “challenging” because of the wide variation in experiences and how they change over time.

“Although management of symptoms is important, a medicalised view of menopause can be disempowering for women, leading to over-treatment and overlooking potential positive effects, such as better mental health with age and freedom from menstruation, menstrual disorders, and contraception,” they write.

They say vasomotor symptoms are patients’ priority for treatment, followed by sleep, concentration and fatigue.

The paper confirms the importance of hormone treatment – “MHT is the only treatment that benefits both vasomotor and genitourinary symptoms and reduces fracture risk” – but argues against using it universally and proposes additional strategies such as cognitive behavioural therapy, hypnosis and lifestyle advice, e.g. on alcohol and smoking.

The literature review finds that combined and systemic forms of MHT appear to increase breast cancer risk, while oestrogen-only forms do not, and that transdermal is safer than ingested systemic MHT for venous thromboembolic disease risk. Topical vaginal oestrogens can reduce dryness and prevent recurrent UTIs in women with primarily genitourinary symptoms.

The authors acknowledge the confusing and complex nature of menopause, citing a qualitative study presenting it as “a normal event, a struggle, a loss of identity, and as a time of liberation and transformation”.

Perceptions around ageing profoundly affect attitudes towards menopause, which vary so much from culture to culture that “the differences are greater than the similarities”.

“Ageism is a powerful social determinant of health, and in countries where menopause is equated with physical and mental decline, it is not surprising that many find this transition daunting … In contexts in which women’s value is predicated on reproduction, menopause tends to reduce social status. By contrast, in societies in which ageing confers respect, such as in Indigenous communities in Australia, menopause is considered less problematic.”

Negative perceptions of menopause, just as with menstruation, “contribute to disempowerment and negative experiences. Women are shamed for menstruating, and then shamed for not menstruating.”

An accompanying editorial says: “The framing of this natural period of transition as a disease of oestrogen deficiency that can be eased only by replacing the missing hormones fuels negative attitudes to menopause and exacerbates stigma.”

Paper No 2 on early menopause says that although data is scarce, it shows that premature ovarian insuffiency (defined as occurring before 40, affecting 2-4% of women) and early menopause (40-44, 8-12%), both spontaneous and iatrogenic, can signal increased risk of chronic disease such as osteoporosis and CVD and higher all-cause mortality. They decrease, however, the risk of oestrogen-sensitive cancers including most breast cancers.

They can also cause psychological distress and increase risk of depression.

Oestrogen replacement is recommended, the paper says, until the typical age of menopause, “but the optimum duration of use is uncertain”.

The paper includes a clinical flowchart for investigation and ongoing care, and calls for more data and research to firm up clinical guidance.

Related

Paper No 3 on mental health says there is a “widespread belief that the menopause transition is universally associated with poor mental health”, but finds – again from scant evidence – no evidence of a universal effect or overall increased risk of new-onset mental illness.

Instead, it finds those with previous major depressive disorder are at risk of recurrence, while those with menopause-related risk factors, such as vasomotor symptoms that keep them awake at night, and those with psychosocial risk factors, such as stressful live events, are prone to depressive symptoms.

It finds no compelling evidence of an increase in anxiety, bipolar disorder, psychosis or suicide risk.

However, the authors say, concerns about mental health may colour people’s expectations and experiences of menopause for the worse.

Clinicians should not automatically attribute psychological symptoms to menopause but investigate and manage them as they would at any other life stage, while being aware of which patients risk a recurrence of depression.

Society, they say, could “learn from societies in which ageing in women confers status and in which views of menopause are more affirming”.

Paper No 4 on menopause and cancer finds many patients in this unfortunate intersection lack access to effective treatments, even in higher-income countries.

Diagnosing menopause after cancer can be challenging since amenorrhoea, as well as symptoms such as fatigue and sexual dysfunction, are common in both.

Gonadotoxic cancer treatments can bring on menopause early, while those already on MHT who have oestrogen-sensitive cancers will be advised to stop, risking a recurrence and worsening of vasomotor symptoms with anti-oestrogen therapy.

“Menopausal symptoms are a common reason for not starting or prematurely stopping endocrine therapy, which directly increases morbidity and mortality from breast cancer,” the paper says. They can also dissuade patients who are genetically prone to ovarian cancer from beneficial oophorectomy.

Patients with oestrogen-receptor-negative cancers should be considered for MHT, with transdermal favoured because of its lower venous thromboembolic risk. Non-hormonal treatments such as some antidepressants and anticonvulsants can improve vasomotor symptoms but not genitourinary symptoms or bone fracture risk.

Of non-pharmacological therapies for menopause symptoms, CBT has the best evidence base, the paper says. It reduces the “interference and bother” of vasomotor symptoms while improving sleep and depressive symptoms.

And once again there is an evidence gap: “Almost all published studies of menopause and cancer are in early breast cancer, and less is known about advanced breast cancer or other cancers in women,” the authors say.

Australian experts approached for comment yesterday welcomed the message of empowerment and the idea that people with menopause should be well informed and heard, but were wary of elements of the findings.

“While it is laudable that menopause and its many presentations is finally being spoken about more openly in both the medical literature and the general population, we must be careful not to undo any good that has already been done and throw out the baby with the bathwater,” said Associate Professor Gino Pecoraro, president of the National Association of Specialist Obstetricians and Gynaecologists, in response to the complaint of overmedicalisation.

“No doctor treating a woman suffering from menopausal symptoms would deny the role of empowerment and nonpharmacological treatments to help sufferers better deal with this transition. However, there remains a place for symptom control with hormonal and nonhormonal medical therapies.”

Professor Jayashri Kulkarni, director of HER Centre Australia at Monash University, took issue with the downplaying of mental ill health related to menopause.

“Menopausal mental ill health can be serious and debilitating for many women,” she said. “Women’s lives are busy and complex but the hormone changes in the brain can be a ‘tipping factor’ causing anxiety, depression and ‘brain fog’. Of course most women do not experience adverse mental health issues related to menopause, but there is a significant group of women who experience severe depression, anxiety and brain fog that impairs their functioning at work or in their relationships.

“There is considerable brain biology research showing the impact of fluctuating gonadal hormones changing brain chemistry and circuitry causing mental ill health. Population surveys are the wrong method to tackle menopause mental illness. Hormone therapy has been shown clinically to be effective in treating menopausal mental ill health thereby helping women resume a good quality of life.”

Professor Susan Davis, director of the Women’s Health Research Program at Monash University, said the principle of empowerment around menopause was not a new one but had been the focus of the Australasian and international menopause societies for years.

She said the messaging around hormone therapy was mixed and potentially confusing.

“Of concern is the promotion of gabapentin and oxybutynin, neither of which are approved in any country for the treatment of menopausal flushes/sweats (vasomotor symptoms) and data for oxybutynin is notably scant. In contrast fezolinetant, which has been approved in the UK, EU, Australia and the US specifically for vasomotor symptoms, has been downplayed to being only modestly effective despite robust evidence which is lacking for these other nonhormonal therapies.

“The authors seem determined to minimise the important role of MHT in helping many women as they reach menopause.”