Constructive criticism is a necessity in medicine, but it often goes sideways. Here’s a model that might help.

“Feedback in educational contexts is information provided to a learner to reduce the gap between current performance and desired goals.” – Sadler 1989

I got some bad feedback.

It left me feeling angry and overly focused on the exchange itself rather than the observation. It also instantaneously impacted on my collegiate relationship in a negative way.

I’ve spent some time trying to figure out what made it such a poor learning experience and how, in less than five minutes, a feedback conversation could dramatically alter a relationship.

Once my anger abated and I thought about it a little, I decided that my colleague wasn’t in fact a bad person, but they did need to work on their feedback delivery and timing. At that point, I should have invited them into my reflection so we could have drawn out some shared learning about the experience. But I let the moment pass, so the learning opportunity was lost, as was the chance to recover some connection and trust.

Having stopped seething and re-engaged my frontal lobes, I imagined the productive conversation we might have had:

Me: Thank you so much for your feedback the other day. Do you have some time to talk about it?

Other: Sure, Dr Davies.

Me: Great. Unfortunately, I couldn’t process the information you gave me because of how it was delivered. It really upset me. I felt a bit ambushed and judged by what you said, and having it delivered in the coffee room in front of others was highly embarrassing. Can we talk about that?

Other: Sure. I’m so sorry. I really didn’t think about how I gave you the information. I just saw your face and it reminded me I needed to say something.

Me: I totally understand. It’s so hard to find the time but I really would have appreciated the consideration. How do you think we might improve the exchange in the future to best hold onto the learning while still supporting our connection?

Other: That’s a good question. Let’s sit down and work through this.

Despite the heavy dusting of stardust and optimism in this imagined example, it is still easy to see where the vulnerable points in this conversation are. As a collegiate dyad we have had to reflect on the situation, build up the courage to discuss difficult topics, manage our emotional responses to each other AND try to pull out some productive learning from it. All in a timely and concise way.

You can see how this stuff goes sideways.

Fortunately, as a mildly impatient, occasionally forgetful GP, who seeks high-yield, low-effort strategies, I think I make a good test subject for effective feedback methodology.

I fell into a rabbit hole of musing and research. Was it possible to develop a quick-to-learn, easy-to-deliver feedback technique that could be used as a scaffold to initiate conversations while maintaining or enhancing connection for someone like me?

After a few literature reviews, several beers and A LOT of conversations with medical educators, directors of medical education, researchers, college gurus and one editor who understands the power of nouns, I came up with a mnemonic that I felt covered most of the deliverable feedback basics.

It may lack the simplicity of SMART, but it does have a certain “stickiness” that helps to satiate knowledge gaps, and like a (premium brand) microwave meal is to hunger it’s convenient, easy to use, fills a hole and if undertaken carefully can be full of nourishment.

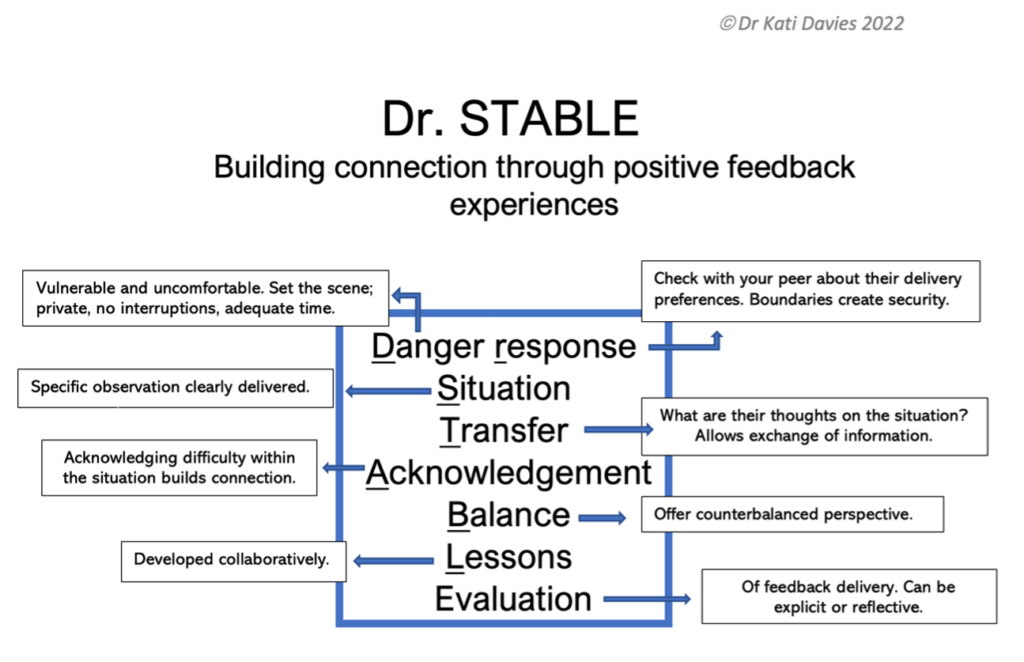

Dr STABLE feedback method: for the time-poor, apathetic, and forgetful

Dr Stable is a mnemonic designed to maximise motivation in the feedback exchange and make it possible to sit with psychological vulnerability by introducing elements to foster supportive relationships.

There are some components I had to leave out to keep the mnemonic “sticky”. Timely delivery of feedback is a must (as agreed by others who know much better than I do), along with the requirement for a pre-existing peer relationship.

To date, like most feedback models, this one has not been validated (though I heartly endorse any one willing to take on the challenge).

Danger and Response: No one likes an ambush. Consider the time and place for an appropriate conversation, and get the recipient’s input.

Situation: What is the situation you wish to discuss? Spit it out. In the wise words of Brené Brown, “Clear is kind, unclear is unkind”.

Transfer: What is the recipient thinking? What information do they wish to transfer? Are you missing critical perspective from their side?

Acknowledgement: No one likes to be left emotionally hanging. This is your chance to build in some connection by acknowledging difficulties faced in the situation.

Balance: This is where pre-existing relationships are helpful; you may have anticipated your colleague’s reaction to feedback and thought of how to navigate this by introducing a positive element.

Lessons: Ideally this would be drawn out through collaborative discussions and mutual curiosity. Suggestive rather than paternalistic language may help. Both parties should aim to learn something.

Evaluation: How did it go? What worked and what didn’t? Did you both learn something and remain connected? If you’re brave enough, ask for feedback on your feedback.

Why do we care about feedback?

Learning how to “do” medicine is multimodal. It relies heavily on apprenticeship and the “see one, do one, teach one” philosophy. Like it or not, we are all teachers and learners irrespective of our career stage.

We owe it to ourselves and the patients we serve to invest time into quality feedback experiences. Doing anything less is robbing ourselves of a tool that helps work towards a rewarding, fulfilling and dynamic career.

The pandemic has demonstrated on a large scale the impact isolation has on stress and mental health. In medical fields It is very easy to be surrounded by people and yet remain isolated.

I don’t know about you, but when things go wrong in my professional life, I use the connection I have with my colleagues to rationalise the situation through informal feedback. The colleagues I trust the most are skilled at helping me to manage my emotional responses in difficult times, draw out areas of improvement for development, while reminding me exactly who I am: a competent, intelligent, fallible person capable of growth.

It takes courage to address our shortcomings and grow beyond them, and that’s almost impossible without connection and support.

Nothing saddens me more than hearing of a doctor suicide where rumours of bullying and disconnection are contributory. Our job is hard enough; why make it harder?

CPD changes regarding performance review are on the horizon – perhaps with the right mindset and strategy, we can springboard off these requirements into some positive change for our educational culture. Two birds with one stone.

It is my hope that frameworks like Dr STABLE might help this become part of our intuitive process. That by consciously embedding positive collegiate exchanges into our performance culture, we start to build a network of connection, trust and respect. Through this, I see a culture that promotes clinical excellence, improved mental wellbeing and greater professional satisfaction … which I think, is something really worth turning up to work for.

Dr Kati Davies is a Canberra-based GP enrolled in the Future Leaders Program and Mentor Program with the RACGP, and a GP Synergy medical supervisor; she fellowed in 2018 and has two young children; her current hero is Brené Brown.

Image c/o Cigcardpix on Flickr