Policymakers, funders and non-GP specialists need to see what GPs add to healthcare, before GPs become extinct.

In my humble opinion, there are more beautiful ecosystems than swamps. Mountains, oceans and rainforests attract more tourists, and efforts to preserve the habitat of whales, orangutans and penguins are always more likely to attract conservation funding than alligators, insects and long-legged birds.

But of course, when we think about the health of the entire planet, beauty and the potential for ecotourism is not the point.

Donald Schon, in his book on professional practice, uses the swamp to describe disciplines like mine, in general practice. He says that no matter what the profession, there is a high, hard ground, overlooking a swamp. On the high ground, manageable problems lend themselves to solution through the application of research-based theory and technique. In the swampy lowland, messy, confusing problems defy technical solution.

“The irony of this situation,” he writes, “is that the problems of the high ground tend to be relatively unimportant, however great their technical interest may be, while in the swamp lie the problems of greatest human concern.”

We all thrive in different habitats. As doctors, we choose our habitat thoughtfully. Many choose the rigor and prestige of the high ground, but I prefer the swamp, despite the fact that many of the important problems I address cannot be solved using methods that are recognised, funded or valued.

As a proud swamp-dweller, I want to share how our habitat is changing, and why we, as GPs, are rapidly becoming an endangered species. Part of the reason is that evidence-based solutions developed on the high grounds are being tossed into the swamp, with predictably uneven results. Worse, GPs are being judged on their ability to adhere to protocols that don’t work in their context.

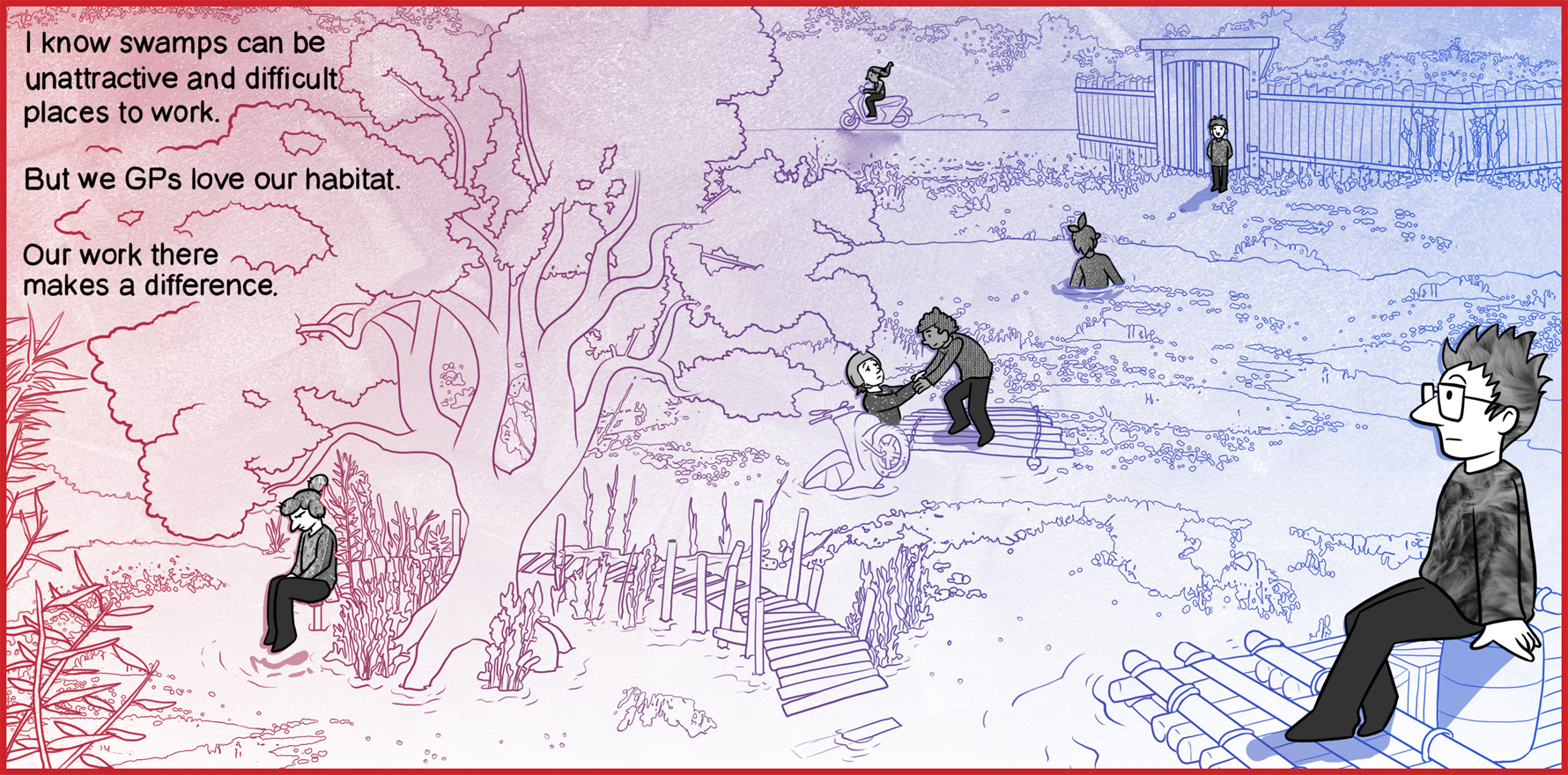

The experience is like receiving a scooter that works beautifully on the high ground, and being required to use it in six inches of water. The sting is in being seen as inept and incompetent because you can’t make the scooter work effectively, and in having your suggestion of supplying rafts go unheard or judged because there is no evidence for its use on the high ground.

No wonder many of us are fleeing the swamp, and fewer young doctors are choosing to work in our worlds.

Changes in the swamp

In recent years, it has been getting more crowded in the swamp, and there are more swamp guides than ever. However, the tradition of taking all comers is eroding. Many specialised swamp guides from multidisciplinary teams and institutions will only take patients who can inhabit the swamp “boardwalks”, the protocol-run systems that give quick, standardised outcomes for well-defined acute illnesses and single chronic diseases.

I used to love those simple consultations – the kid with mild first episode asthma; the women worried about pityriasis versicolor; the sprained ankle. These consultations run on boardwalks. We have an easy, almost automatic spiel, the problem gets solved, and the patient gets across the swamp very quickly to return to their own habitat. We all feel good about ourselves, and we conserve our energy for the patients where boardwalks are not available.

Boardwalk patients don’t see people like me anymore. They go to the nurse-run clinic, or the pharmacists, or the internet. There is no problem with that, except that it leaves people like me leading patients with complex needs through the deepest, darkest depths, with no respite. There are no more resources, just increasing complexity, with no time on the boardwalks to catch my breath. Worse, it leaves me with unfixable suffering, which is not only deeply exhausting, it is also invisible labour with slow (if any) progress. Nobody can see how hard I need to work just to keep a patient afloat. From the high ground, it looks like I am going nowhere.

It is also financially ruinous. You can charge more on the boardwalks and the Medicare rebate is higher. Worse, different parts of the swamp are differently valued. Patient who need guidance in the “nicer”, cleaner, and more acceptable parts of the swamp, like dermatology and diabetes, are funded more per minute than those with lower prestige needs like dementia, depression and entrenched despair.

These lower prestige diseases are managed more often by women, and like any industry, this tends to devalue the work.

Changes in the high ground

I used to be a gatekeeper for the high ground. When I started my career, I could usually find a way to get the patient the care they needed. Sometimes, there was a bit of begging, but generally speaking, I could talk to the non-GP specialist and between us we could open most gates. However, the gates to the high ground are now locked, and we no longer have the keys.

The gatekeepers are now inside the gates, and I have to beg them to open the doors. Worse, these gatekeepers are often administrative staff or health professionals with protocol-based triage criteria who simply do not understand that I need help. The passports needed to get past these gatekeepers are complex and bewildering, and often restrict access to care for those without the literacy or health literacy to complete the paperwork.

The solutions offered in secondary or tertiary care may not fit my patient’s needs, but this does not mean they belong in the swamp. Sometimes I need advice, or support, or a second opinion. I need a consultant, not a specialist. But my needs are not an issue for the gatekeepers, who work for the high-ground institutions.

We are in a position at the moment where I have all the responsibility for gatekeeping, but none of the power.

The alligator in the room that no one will acknowledge is that we cannot or will not provide best practice care for everyone. In these circumstances, we can either give everyone affordable primary generalist care, and limit access to secondary and tertiary care, which is politically unacceptable, or we can reduce the numbers of people accessing care at all. This cannot be overt, because it is uncomfortable to acknowledge that we have abandoned our responsibilities to those who live with disadvantage.

Instead, we make access to specialised services so difficult and costly, it is only available to those with the resources to use them. The rich have high-ground resorts, private healthcare systems that have concierge systems to help them navigate to the care they want. The poor have administrative and clinical systems that are so complex, they can’t afford to use healthcare at all. The literacy, healthcare literacy, transport, childcare and other costs required to access best practice care is too high.

For those with multimorbidity, the situation is even harder. The consumer and carer are being asked to do the work of leaping from high ground to high ground, without safety nets. This is a full-time job. Many are just too tired to manage any of this, and so they stay in the swamp with us. Unfortunately, the narrative is usually that they “choose” this path as “healthcare consumers”.

In fact, we fail them. Consistently.

I know swamps can be unattractive and difficult places to work. I know we GPs come across as rugged individualists with non-standard approaches optimised for our own diverse habitats. I know some of us are lazy, incompetent or dangerous, but this is a feature of any profession, of course.

The tipping point for me is that those of us who are masters of their field can no longer provide the care they are trained to do, and are leaving because the swamp is such a discouraging and increasingly dangerous place to be. Too many of us are drowning.

We love our habitat. Our work makes a difference. It’s a shame more policymakers, funders and clinicians don’t see what it is we add to the world of healthcare, before GPs as we know them today become extinct.

Associate Professor Louise Stone is a working GP, and lectures in the social foundations of medicine in the ANU Medical School. Find her on Twitter @GPswampwarrior.

Dr Erin Walsh is a research fellow at the Population Health Exchange at ANU. Her current focus is the use of visualisation as a tool for communicating population health information, with ongoing interests in cross-disciplinary methodological synthesis.