When it comes to fighting doping in sport, are we using a sledgehammer to crack a walnut?

When everyone from the Australian government down to the local sports club signs a commitment to anti-doping in sport, one might be misled into thinking that everyone knows and agrees on what that actually means.

Since the birth of the World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA) in 1999, billions of dollars have been spent on testing and prosecuting people for anti-doping violations in a bid to enforce a drug-free sporting community.

But despite this, fundamental questions remain about what actually qualifies as sports doping, and why it is important to stamp it out.

“People are agreeing to what they think anti-doping should be, not what it actually is,” says international anti-doping policy expert, Dr Jason Mazanov.

In principle, an anti-doping policy aims to control the use of drugs and drug technology by competitors, particularly those which are designed to enhance performance.

The Australian psychologist has just published a book on drugs control in sport and the failures of the anti-doping industry.

Doping in sport is almost universally considered to be inexcusable, and so important as to be included in the Olympic Oath, to be said at one of the most prominent sporting events in the world.

But drugs are still a significant part of sport, whether prohibited or not, and like the “war on drugs” in the wider community, the prohibitionist approach has had a range of unintended consequences.

The code that governs anti-doping has a level of complexity on par with tax law, and yet athletes and parents are expected to navigate that with minimal guidance. While informed consent for medical procedures is an intensely important part of medical practice, consent to anti-doping compliance is incredibly poorly understood, Dr Mazanov says.

“I don’t think the administrative and political eliters who formulated the code understand what the implications of their administrative frameworks are. Nobody seems to know. Everyone just wanders around assuming it’s better than it is.”

In reality, efforts to protect the integrity of sport now mean it has become acceptable for children as young as nine-years-old to be forced to urinate, mostly naked, in front of strangers, and for 18-year-old lives and livelihoods to be destroyed over cold and flu medications.

“This is why I take the view that we absolutely must have drug control in sport, but we need to do a more enlightened version of it than anti-doping. It’s medieval, it’s inquisitorial, it’s not 21st century, humane drug control policy,” Dr Mazanov says.

Why do we need anti-doping?

Protecting players’ health and ensuring that competition occurs on an even playing field are two of the most often cited reasons to fight doping in sport.

“For most people anti-doping is a vexed issue, because it’s not as effective or not nearly as effective as it should be, but it’s better than doing nothing,” says Daryl Adair, Associate Professor of sports management at the University of Technology Sydney.

Though flawed, people worry the alternative would be worse.

Without anti-doping, people fear we would be left with the “Pharmacy Olympics”, with Pfizer-sponsored runners competing with Bayer-sponsored runners for the 100-metre sprint, he says.

In management terms, this is known as a “wicked problem”.

“It’s so multifaceted and so complex that every kind of solution and every kind of effort to respond doesn’t seem to meet the objectives that are required to make it work,” he explains.

One example is microdosing, commonly used in sports such as cycling. Microdosing involves consuming minute amounts of a drug such as erythropoietin (EPO) over extended periods of time to improve aerobic capacity and endurance.

Because athletes must be available for drug testing 365 days a year, between 6am and 11pm, it is reportedly possible to take small amounts just after 11pm and be fine during testing hours.

“Drug testing is not foolproof. It makes us feel better that something is happening – but it’s like an intelligence test because the smart won’t get caught,” he says.

“In some ways, it’s a PR exercise.”

As well as the moral or emotional arguments against drugs in sport, sport is a global business, with advertising dollars on the line, and parents of children who idolise sports players to appease.

But Dr Mazanov argues that the whole discourse rests on flawed principles.

“When you look at proportion of variation in sports performance that can be attributed to drugs versus other things, the things that are really important to someone’s athletic success are their genetics, their access to training and whether they come from a rich country,” he says.

Athletes in wealthy countries such as the US, Germany, China and Russia are more likely to win a medal than someone from Kenya or Somalia. So the argument that doping will lead to inequality is disingenuous, he says.

“What we’re really doing is talking about the variations on the very fringes among the very elite of the wealthiest countries in the world, so that they can then impose drug control on everybody.”

It’s not working

“It is no longer a question of whether athletes use drugs. The evidence shows that almost all athletes will compete with some kind of pharmaceutically derived substance in their body, whether that’s a supplement or something else,” Dr Mazanov says.

Anti-doping rules have changed the drugs and the manner in which people consume them, but the majority of athletes end up taking a combination of licit drugs, supplements, over-the counter drugs and prescription drugs.

“New drugs come onto the market all the time that athletes use to gain a performance enhancing advantage. Athletes will often compete with pain killers in their system and get injections to overcome injuries,” he says.

Some of these are performance enhancing, and some are not. Caffeine, which is a well-established performance-enhancing drug, is allowed. Whereas marijuana, which is unlikely to be performance enhancing, is banned.

“To say that doping is somehow morally wrong, and you can’t have an artificial advantage, is ridiculous,” Dr Mazanov says.

Nevertheless, effective drug testing in elite sports costs an estimated $US29,000 per athlete. And now WADA wants a 10-fold increase in the amount of money it receives – taking its annual spend from $US30 million to $US300 million.

Implications

The powers of WADA and ASADA are wide reaching. WADA’s code and supporting documents run over 1000 pages long, before factoring in the Australian Sports Anti-doping Authority (ASADA) Act. The Prohibited List itself runs to 10 pages.

“The code is designed to penetrate all levels of sport, from elite male sport through to membership-based recreational sport,” Dr Mazanov says.

“WADA is a necessary vehicle […] but it is far too complicated,” former ASADA boss Richard Ings said at a recent panel at the University of Technology Sydney.

Doping is defined by WADA as any behaviour that breaches one of their 10 anti-doping rules. This ranges from a positive test for a prohibited substance to failing to report an anti-doping rule violation.

The Prohibited List encompasses drugs that meet two of three tests; they potentially or actually enhance sporting performance, they potentially or actually pose a health risk to athletes, or they violate the Spirit of Sport statement, Dr Mazanov explains.

In 2013, the Australian government enabled ASADA to coerce citizens into giving evidence for investigations into doping.

Though parliament specifically pulled back from allowing individuals to be compelled into giving evidence that would self-incriminate, subsequent iterations of the code have included this, making it a contractual obligation for players.

On top of this remarkable scope of power, athletes are required to report their whereabouts, ahead of time, every day of the year. These kinds of regulations have led to grumblings that athletes have fewer rights than convicted criminals.

The Essendon Football Club saga highlights the distressing nature of these policies. After three years of a very public ASADA investigation into the doping of 34 players, they were ultimately found not guilty by the Australian Football League tribunal. WADA appealed the decision by taking it directly to the highest sporting court in the world.

“The systematic exclusion of athletes from having an equal voice in matters that directly affect their lives has been one of the critical failures of anti-doping, from the distressing and degrading experience of urinating in front of a stranger to being coerced into a surveillance system that prevents freedom of movement,” Dr Mazanov says.

But along with the moralistic attitude to doping comes the assumption that failure to comply with anti-doping regulations is a fault of the individual.

“This assumption has prevailed, even though it was well understood before the first iteration of the code, that the practice of drug behaviour in sport occurs within a complex web of social and institutional structures,” Dr Mazanov says.

For women

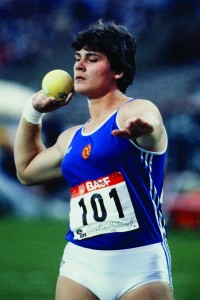

When an athlete is called in for a drug test, they are required to be naked from nipple to knee, with an official witness there to view the urine leaving the urethra and collected in the container.

Around one third of men and half of all women report finding the experience distressing.

For Dr Mazanov, these figures raise the question of equality between genders. Anti-doping policies are specifically worded to treat men and women and children the same. But they are guided by elite male sport, which is a realm where men appear to be doping at around five times the rate of women, and using different drugs.

“What I would suggest is that if 50% of men found drug testing distressing, would we have actually come up with a different approach,” Dr Mazanov says.

What’s more, it calls to mind a previous practice where medical scrutiny of female athletes was introduced in order to prevent men from posing as women.

This was eventually abandoned because it was deemed to be degrading to women, but a very similar practice is in place with urine testing.

“We are saying we don’t care if we degrade our women by doing this, we will proceed because of the importance of integrity of sport,” Dr Mazanov says.

For children

This practice gets even more concerning when it comes to child athletes.

The youngest ever child sanctioned for an anti-doping violation was 12, and the youngest child drug tested under the anti-doping framework that we know of was nine years old, Dr Mazanov says.

Putting a child into that situation raises some ethical problems – can the child meaningfully consent to that? It also raises problems for the parent and coach. Both have the ability to opt out of the test on behalf of the child, but doing so would automatically draw a sanction, potentially of four years. It is even more problematic for the coach, who could also be sanctioned for not doing everything in their power to be anti-doping compliant.

“It’s all to protect the integrity of the 100m Olympic final. But I don’t see how forcing a child to urinate in front of strangers like that is protecting the integrity of sport.”

It’s a human rights issue for these children, that is taking place to stop a small proportion of children, Dr Mazanov says. Data from WADA in 2013 found an analytical positive rate of 0.8%.

It is hard to imagine the community reaction if these powers were suggested to stop cheating in exams, or allowed to be used by police in train stations to stop illicit drug use in the community.

And it must be remembered that children found to have prohibited substances in their urine probably took them on the advice of their parents and coaches, but leaves them on a lifetime public register.

For doctors

Research suggests that doctors, like many other professionals in the field, don’t have a good understanding of the WADA code.

“If an athlete comes to them seeking an exemption, it’s not clear to me that they have the appropriate medical knowledge to navigate that,” says Professor Adair.

“The WADA code is an extremely long and complicated document to make sense of, because some substances are legitimate in competition and some are legitimate out of competition.”

The risk is that something prescribed could inadvertently land an athlete in hot water for a doping violation, and under the principle of “strict liability”, the athlete is responsible for whatever is in their body, be it a contaminated supplement or a heart medication.

The wide-reaching powers of WADA provide a dilemma for medical professionals.

For example, an athlete may disclose to their GP they have been smoking marijuana to deal with competition anxiety, or are recovering from anabolic steroid abuse, and so the GP becomes aware that the athlete is violating the World Anti-Doping code.

Under WADA’s regulations, any support personnel – including medical professionals – must report this to the anti-doping authorities. Aiding, abetting, covering up or other types of complicity qualifies as an anti-doping violation.

Of course, reporting this potentially undermines the therapeutic relationship between the doctor and their patient, and has business implications for doctors who work with athletes.

The code’s “prohibited association” rule also prohibits an athlete from associating with another athlete or athlete-support person who has previously committed an anti-doping violation.

While the primary obligation is towards the patients themselves, the doctor treating the athlete has a responsibility to know what’s on the list and what amounts to a violation, Georgie Haysom, head of advocacy at Avant, says.

“In this country where lots of people play sport, it is something a doctor should be aware of. Certainly if you are treating a patient at an upper level of sporting competition,” she says.

Sport is a modern business and so long as the incentive to win remains, doping is likely to continue.

In the meantime, the sports community continues to ask where the line is, and what is worth sacrificing to protect the integrity of sport.

Some of the more traumatic outcomes of anti-doping may be overcome by more sophisticated technology. If an athlete could swallow a pill containing chemically coded urinary dye markers, that could overcome the need to be naked and examined by a witness.

But at the moment, the current system is administratively easier.

“It’s technically convenient, but it does so at the risk of the integrity of the athlete,” Dr Mazanov says.

“Once again, it is reaffirming that the athlete is the subordinate to sport – that the athlete is the object of sport, not the subject.”