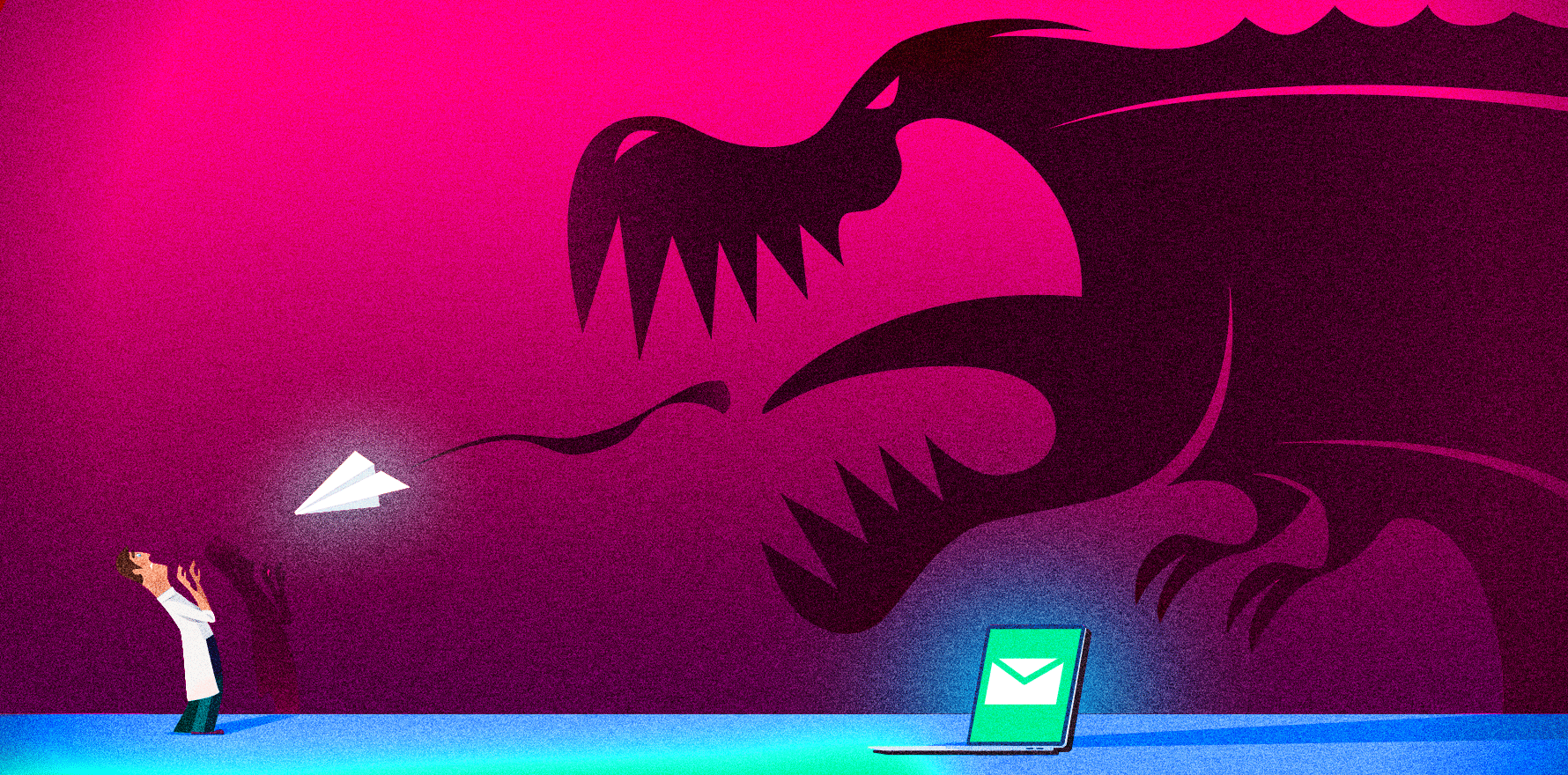

A notification can hurt, but it should never be the end of the world.

Ask any doctor what they fear the most in their career and most will say: being caught up in a complaints process.

In fact, most doctors won’t even offer that, because they can’t even entertain the idea that it might happen to them.

It’s fair to say that most of us have an “us” and “them” mentality about who receives a patient complaint. Complaints are things that happen to “other” doctors, yet we fear we may become an “other” doctor someday too. Because the concept is so distressing, doctors don’t prepare for this scenario. They don’t even let it enter their mind. So, when it does happen, the immediate reaction is to panic and go underground.

As it’s Crazy Socks 4 Docs Day this Friday, I want to share a few tips from my own experience of how not to handle a complaint, for the sake of your mental health, and remind you that help is at hand.

It is easy to be blindsided by an email with the following dread words in the subject heading, often late on a busy Friday afternoon, and if you’re really unlucky, just as the clock is ticking down to a much-needed holiday:

AHPRA Notification — Private and Confidential

This leads to a frenetic stroll down through the content. And realising that, attached to the body of the email, which contains an enormous amount of detail about keeping emotionally safe in the wake of the news, there is a PDF document outlining the name of the complainant, and some of the details.

It does take time to process these details because, often, the matter occurred some months ago. Shards of recollection try to compete with the autonomic response of palpitations, dizziness and the emotional sense of dread. Then the email states who went the extra mile, deciding something that did or did not occur led to them to using the “C” word via a portal on a website belonging to the biggest regulators of our professional lives.

Why is it difficult to comprehend that somebody would complain about us?

In the world we live in, we deal with people who are in pain, who feel aggrieved or have anger to displace, and have every right to complain about our care, or lack of it. They have every right to ask for an answer. On many occasions they are justified to ask, they may simply have misunderstood, or they may have suffered an adverse outcome. People have every right to complain about our care. Third-party regulators have every right to ensure that patients are safe. Third-party regulators don’t fret about the small stuff.

I’m here to tell you that you should not fret either.

I have endured notifications from aggrieved patients, often in psychiatry private practice, and it has taken months to conclude that there was no cause for complaint. That didn’t mean I didn’t run off the rails, fall apart, blame myself, go on a huge guilt trip and doubt interactions with other patients long after the complaint was thrown in the bin. I was paralysed from writing good clinical notes, because my notes had been scrutinised as part of the complaints process. They had saved me, but my focus had changed. I believed I should no longer write good clinical notes that would assist my care of my patient but write them as if a lawyer would read them, picking apart every single word, line, decision and action. I stopped enjoying medicine. I was fearful of taking on a new patient.

I didn’t talk to anybody about it except my medical defence organisation.

Although I had to take the process extremely seriously, I did not need to fret as much as I did. What I have learnt is that I should have been aware that a complaint is just that. It is the beginning of a conversation to clarify any situation or outcome. But because of the context, I panicked unnecessarily and let the situation take on an all-consuming life of its own.

My experiences led me to write about the event, first anonymously because I was so fearful of being judged. Nobody talks about receiving a notification, yet MDO claims managers will tell you that new cases are opened multiple times a day, usually by doctors who are talking through tears and convinced their life is over.

Others are simply livid.

After a period of time, I recognised that we are very ill prepared to manage complaints during our training. We presume that if we do our ridiculously exceptional best all the time for absolutely everybody, we will be OK. And the truth is, perfectionism does not guarantee we finish our careers complaint-free. We can finish with the knowledge that we certainly helped many, but a very few might not be helped.

A complaint, even if you are found to have made an error, does not erase your years of otherwise exceptional service.

After all, if we didn’t make mistakes, or if systems didn’t let us down, or if people were always grateful and satisfied, we wouldn’t need medical indemnity insurance. Just as we do not plan to have a motor vehicle accident when we take to the road. But we take out comprehensive car insurance.

Risk is risk and can always be mitigated for and insured against. In fact, the risk of defending a patient complaint should be part of a full risk register of a doctor’s practice and be insured against.

After working in this space as a doctor’s doctor for some years and now formally as a complaints outsourcer, I can offer some really good advice about what to do if you happen to receive that AHPRA email on a late Friday afternoon. Advice that, if we’d received it as part of our medical training, we might be better equipped to deal with, and decide how much we should or shouldn’t care about the “C” word.

1. Don’t panic. Believe me, I know this stuff feels extremely personal; after all, it’s the regulator writing to you personally about something you shared or did in a confidential patient setting, right? Wrong. Our regulator is not capable of making this process personal. If they did, they would sieve out notifications, triage accordingly and apply a strategic approach to keeping the doctor and the notifier informed in a timely manner. Instead, what happens is, no matter the situation, the same email is sent with the same heading and cover letter. The body of the complaint is merely cut and pasted into the template. So, although the complaint feels extremely personal, it’s anything but.

2. Don’t go to ground. You need your team around you. After all, remember, this process is going to take some time and you deserve to stay focused on the important things in your life. Deal with it as soon as you can. Placing the email in a folder, or putting it in the bottom of your drawer, will not help. Tell your family, your friends, your mentors, your peers. You’ll be surprised how supportive they can be and how they will open up about their experiences.

3. Contact your MDO, even if the matter happened while you were working in a public hospital and is dealt with by their team. Claims managers work around the clock. Get that process going. And it is a process, not a personal vengeful attack, although it can feel that way. Do not contact the regulator until you have done this. It will save you time and ensure you are best represented.

4. Contact any doctor support services available to you and see your GP. It is a fact that, tragically, some doctors contemplate suicide when blindsided by a complaint. Make sure you are OK.

5. As far as you can, act objectively and not reactively. I have seen angry doctors contact their local MP or even the media in a very reactive state. It rarely helps. Contacting the patient will not help either. Now is the time to look after yourself.

6. Be realistic. No matter how big or how trivial the matter is, nothing is sorted within 3-6 months. If you add the delay in notifying you as well, even the most minor situation may take the best part of a year to close. Recently, notifiers such as AHPRA have admitted there are delays to notifying doctors about complaints. They often refer matters on to other regulators, such as the Mental Health Complaints Commission in Victoria, even if they see no reason to investigate further. They may also impose a need to engage in professional education or upskilling, which can be a very costly and time-consuming exercise in itself.

7. Know what your MDO can and can’t do. They are your insurance company. Just as you have an insurance company to settle a matter after a vehicle collision, they will look at both sides and work towards resolution of the claim. In this way, they are very different from a lawyer you engage independently, should you choose to. They can assist with helping you prepare a report for the regulator that provides the information they are seeking. They can assist with reports for the coroner and may support you through this as well. Check the fine print. Not all MDOs are the same. And just as with your car insurer, your premium will rise after you make a claim, even if there is no basis to it in the end.

8. Tell the truth, always. If your notes don’t reflect the information needed for the regulator, never fabricate notes or amend them. The smallest of claims can turn into the biggest if there is suspicion that the facts have changed.

9. Take a break from work, if possible. Even a long weekend away to let the situation sink in, so that your feelings, although understandable, don’t tarnish all the interactions with the rest of your patients and your colleagues or staff. By doing so, you can keep perspective about one patient interaction that needs to be clarified, and the countless other interactions happening right around you.

10. This is where a “complaints outsourcer” comes in. Work out how much of the process can be outsourced to somebody with the skills and expertise to relieve you of the day-to-day burden of the process. Consider that even the most basic of complaints will consume at least 10 hours of work and cost how much that is in lost billings and personal life. Reduce your hypersensitivity to scrolling through emails or become anxious every time the phone rings. Give the task to somebody who won’t fret about it but will definitely care about you.

Dr Helen Schultz is a consultant psychiatrist with almost 20 years’ experience in doctor mental health, who now offers “complaints outsourcing” – practical assistance for dealing with a regulatory or professional third party. Contact her at helen@drhelenschultz.com