You can't lay all the blame for increased hospital demand at the feet of older Australians, writes Stephen Duckett

You can’t lay all the blame for increased hospital demand at the feet of older Australians, writes Stephen Duckett.

Australian Medical Association president Michael Gannon last week headed his list of reasons for increased pressure on the health system with population ageing.

He’s not alone: commentators regularly claim that population ageing is a major pressure point for hospitals.

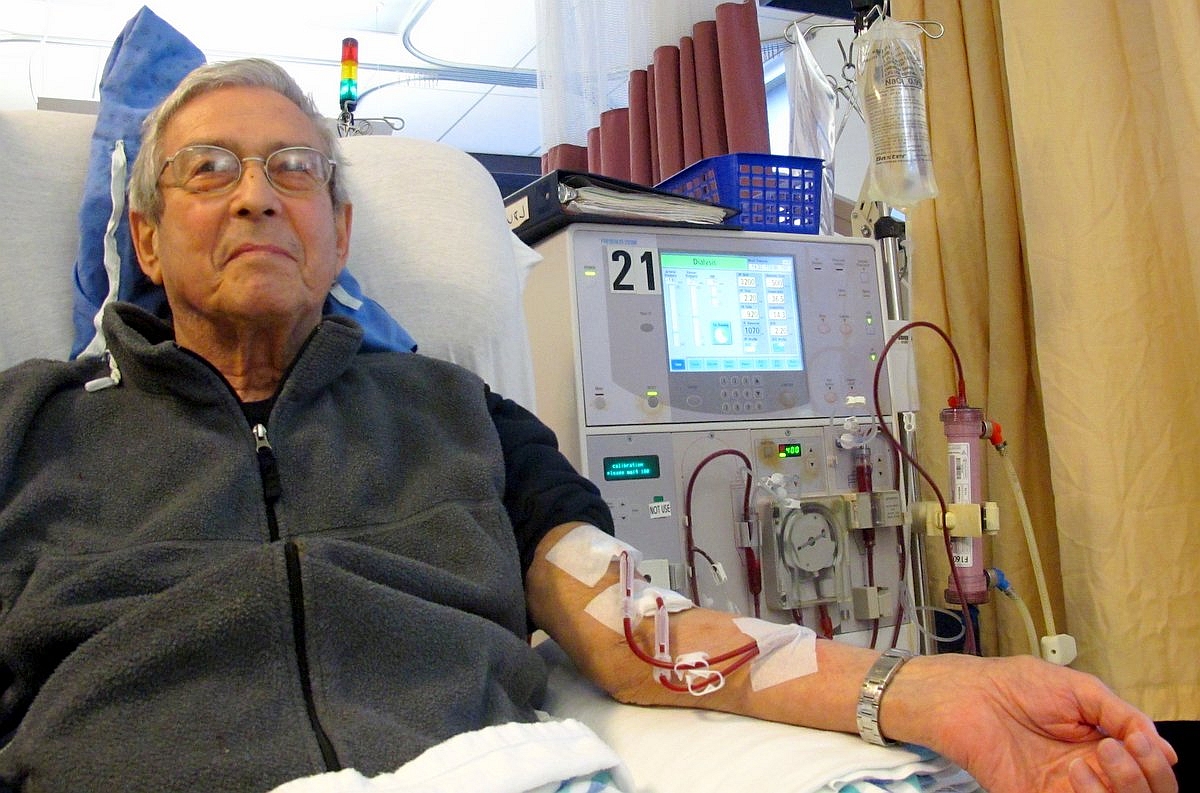

The logic is obvious – compared to younger people, older people have higher rates of illness and consequently higher rates of visits to doctors and admissions to hospitals. Each Australian aged over 85 has almost 1.5 admissions per year – about three times the rate for people aged 30 to 34.

But older patients are not solely responsible for the growth in demand for hospital services.

Doing lots more with just a little more

In the decade to 2014-15, the latest year for which statistics are available, hospital admissions for people aged over 85 more than doubled. This equates to an additional 364,000 admissions.

Because of an increase in the proportion of same-day admissions and reductions in the length of stays, these extra admissions could be treated in just 40% more hospital days.

Rates of admission to hospital

What is driving demand?

As well as the population ageing, big changes are occurring in the way older people are treated. Better anaesthetic agents mean operations are safer for older people than before. This increases the likelihood that the benefits and risks weigh in favour of undertaking a procedure.

Because older people are living longer, they have a longer life expectancy at any given time than they did ten years ago. That also makes the foreseeable benefit of a procedure greater than it was before.

The fact that more people are surviving into later life with chronic conditions such as heart disease and cancer also increases the likelihood of hospital admissions.

Finally, hospitals and their staff can intervene more, which increases the risk of “futile care”. A recent systematic review suggests that as many as one-third of all patients receive “non-beneficial treatments”.

All these factors, taken together, are pushing up the admission rate for older people.

But that’s not the whole story, or even the main part of it.

In 2014-15, there were 3 million more hospital admissions than in 2004-05. More than 60% of that increase is attributable to changes in the under 70 population – in part the increase in the number of people under 70, and in part an increase in the rate that people under 70 are admitted to hospital.

Increase in hospital admissions

Just over one-fifth of the increase in hospital admissions was due to changing treatment patterns for older people. Less than one-fifth of the increase in admissions was attributable to the increase in the number of people aged 70 and older.

So what people talk about as the major cause of increased admissions – an ageing population – is in fact only a relatively small contributor to the growth in hospital admissions.

Don’t throw older people on the scrap heap

Loose talk about ageing of the population causing increased pressure on the system carries a cost. It makes older people feel as if they are a burden and not valued.

There’s not much we can do that is legal to stop the ageing of the population, so what we need to do is to make sure the system adapts to cope with ageing. For one thing, it needs to be better designed to manage chronic conditions.

We also need to remember that the health system is there to benefit people. A hospital admission can lead to reduced pain and discomfort, an increase in life expectancy, or both.

The debate about ageing needs to move away from claiming the sky will fall in because of the ageing of the population. We need a more sophisticated public discussion to understand better the bigger issue, which is the change in treatment patterns.

We need to focus on whether every admission is justified and whether the procedures performed are supported by good evidence. We also need to consider whether care at the end of life is appropriate and whether people who might otherwise be admitted to hospital have the option of dying at home, or, if admitted, are not subject to invasive treatments of little benefit.

Stephen Duckett will present at the Council of Ageing’s annual policy forum session, Can the health system afford all these older people?

This article first appeared on theconversation.com website