GPs can now notify services about domestic violence, but could breaching confidentiality further endanger patients?

When Susan Jones first attended a clinic for injuries sustained from rape in 2001, the GP gave her a pamphlet for a women’s helpline.

Susan (not her real name) disposed of the pamphlet in case her husband found it.

The GP directly asked Susan if she had been raped. But, at the time, Susan did not understand that it was possible for a husband to rape his wife.

Eight years later, after finally leaving her husband following four previous attempts, Susan and her four sons became homeless. They spent a year camping in parks and living out of a car.

Their many attempts to overcome homelessness were thwarted by a limited availability of suitable accommodation, lack of money and bureaucracy.

Susan’s story, recorded as part of the Victorian Commission into Domestic Violence, is sadly familiar.

Statistically, GPs see around five women every week that have experienced physical, emotional or sexual intimate-partner abuse in the past year. The GP may be the only person a woman will tell. Men also experience domestic violence, but less frequently than women.

GPs have long recognised their role in asking women about violence, developing safety plans and making referrals. But a recent change in NSW regulations is asking GPs to be even more proactive.

As of May this year, GPs can alert welfare services about domestic violence without the patient’s consent in cases where the person is at serious risk of harm.

The only exception is where the GP determines that such an alert may, in fact, increase the threat.

The change recognises that patients are more likely to disclose abuse to a trusted GP than to the police. This change enables GPs to take some action to protect the patient without the fear of instigating a full-blown legal process that is sometimes associated with official reporting, says NSW police commissioner Michael Fuller.

But AMA NSW has slammed the change, saying it could discourage patients from being open with their GP. Patients are the best judge of their own safety, says vice president Dr Kean-Seng Lim, a GP based in western Sydney.

Some GPs fear that untimely, non-consensual interference could escalate violence and further isolate the patient.

“Our role as doctors is to support people through whatever decision they decide to make,” Sydney GP Dr Danielle McMullen says. “I don’t think that going above their heads and engaging services without their consent would help them to remain safer.”

The Framework

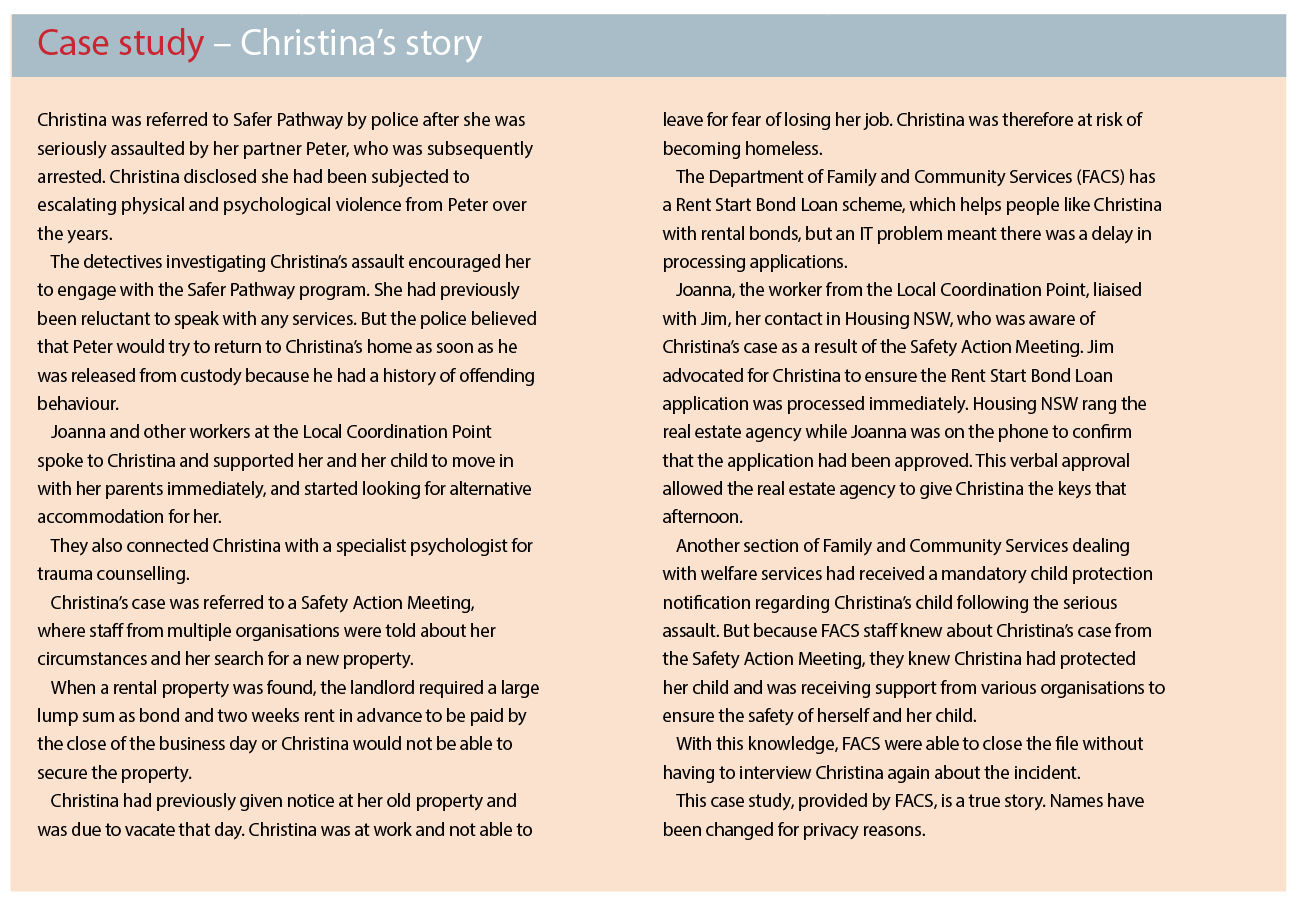

The NSW Government launched its “It Stops Here Safer Pathway” model in 2014 with much fanfare. Under this new “streamlined and integrated approach”, the police (and later GPs) refer all domestic violence matters to a specialist service called a Local Coordination Point (LCP). LCP staff then call the women within one business day and offer an immediate safety plan, as well as referrals to housing, legal and financial services.

Women are, of course, free to decline any offers of support. But according to Maria Le Breton, the director of WDVCAS, these calls are generally quite well received.

The model centralises the coordination of services. Separate agencies talk to each other, instead of victims being required to contact each service and repeat their story many times over.

In order to move swiftly to protect women in life-threatening situations, information is sometimes shared between agencies without the consent of the victim.

LCP workers also refer the most potentially dangerous cases of domestic violence to a “safety action meeting”. These meetings are attended by police, housing services, child protection services, corrective services, health and education representatives, and any relevant non-government organisations.

The first LCPs were established in July 2015. They have now been rolled out in 26 regions, including Sydney, Wagga Wagga, the Hunter Valley, the Blue Mountains and the Illawarra (see the full list here: bit.ly/2sVEtwE).

While Safer Pathways was new, the Women’s Domestic Violence Court Advocacy Service NSW (WDVCAS), which operates the LCPs, is 20 years old.

The major issue some GPs have with this system is the potential breakdown in confidentiality. Once a GP releases patient information, it can be passed on from one agency to another without the patient or the GP knowing where it has gone.

“And you can actually put patients more at risk by them getting a phone call that they are not expecting,” says Dr Charlotte Hespe, the head of General Practice and Primary Care Research at the University of Notre Dame in Sydney. “I would highly doubt that GPs would do referrals without [patients’] consent because it is just not best practice in any way.”

Going over a patient’s head could damage trust, which is the bedrock of all medical care. It takes away autonomy from people who have already been made to feel powerless and controlled by their partner.

“Generally speaking, these are people who are already highly vulnerable and being able to trust people is a really big issue,” says Dr Hespe. “If things are done without permission then there are definitely issues around what effect that might have on your relationship going forward.”

Supporting women through domestic violence is a long and complex process. It takes, on average, seven attempts for a woman to separate from an abusive partner, and some will never leave. GPs may have a more positive influence if they operate in alignment with the patient’s wishes rather than independently taking action.

“And if you are not getting consent, why aren’t you getting consent?” asks Dr Hespe. “If it is a mental-health issue then … should you be accessing acute health services rather than domestic violence services?”

Another problem is that the new referral pathway is being conflated with mandatory reporting in the press, says Dr McMullen. Alarmist media reports could dissuade women from telling their GP about domestic violence.The only region where all adults are legally required to report domestic violence to police is the Northern Territory.

Calming fears

Advocates for non-consensual referrals argue the new pathway provides a welcome clarification for GPs.

GPs are already entitled (and in some cases obligated) to break patient confidentiality when patients attend with stab wounds, lacerations, gunshot wounds or suspicious fractures.

But to date, it has been unclear whether information sharing could occur between health practitioners and support services, said Dr Kelsey Hegarty, a GP and professor of family violence prevention at The University of Melbourne.

The new regulations specify the situations where GPs might consider circumventing the privacy principle and talk to other agencies.

Encountering and managing cases of domestic violence can be challenging in general practice, says Professor Deborah Bateson, the Medical Director of Family Planning NSW and a Clinical Associate Professor at The University of Sydney.

There are a number of resources available to GPs, including “It’s Time to Talk” (bit.ly/1kh4yin) and the RACGP White Paper (bit.ly/2stKvaF). But this change to regulations provides a much clearer framework, argues Professor Bateson.

Professor Bateson stresses it would only be in extremely rare, life-threatening situations, after all other options had been exhausted that GPs would consider contacting these services without the patient’s consent.

GPs can ask women to assess their own safety, use the Domestic Violence Safety Assessment Tool (bit.ly/2tD3H6d), or else use their professional judgment to determine the level of risk. However, they would almost always be working in consultation with specialist services and colleagues in these situations.

They would also usually inform the patient of the limits of confidentiality and tell the victim that they were making a referral without consent.

Safety first

Maria Le Breton, who is currently heading up the LCP project, says she completely understands the concerns raised by GPs. In 2015, when this system was starting to be rolled out across the state, other service providers were similarly apprehensive about breaches of privacy, including domestic and family violence services and child protection services.

“But from what we have seen, those concerns haven’t come to fruition,” says Ms Le Breton.

Intimate-partner violence is responsible for more ill health and premature death in Australian women under the age of 45 than any other risk factors, including high blood pressure, obesity and smoking.1 And barriers to information-sharing are thought to contribute to this statistic.

“So what the legislation is trying to do is to balance the woman’s rights to confidentiality with providing a response that better secures their safety,” says Ms Le Breton.

There are strict protocols (bit.ly/2uwUWXt) around the sharing of information under Part 13A of the Crimes (Domestic and Personal Violence) Act 2007. But patients may not be aware of these limitations. “People probably require a bit of an explanation about how that information might be used and how it will be protected,” says Ms Le Breton.

“A lot of people’s fears can be alleviated with that information.”

For instance, services can’t just share any information that they hold. The information has to be specifically relevant to the threat experienced by the victim. And all professionals that attend a Safety Action Meeting, including police, have to sign a confidentiality agreement.

One of the major issues raised by GPs is that even being contacted by support services might put women at greater risk if the perpetrator finds out and retaliates.

“That’s a common concern for people,” says Ms Le Breton.

However, in Ms Le Breton’s experience, the benefits of receiving an offer of support often outweigh the risks, especially when the person using violence has deliberately isolated the victim. Moreover, LCP staff work with extreme sensitivity. “Our services are very, very aware of the risks,” she adds.

“They are really quite careful and clever in the way they contact women.”

For example, staff wouldn’t leave a message on a voicemail.

The protocol also specifies that staff should always:

• call from a blocked number

• check they are speaking with the victim before identifying themselves or the service from which they are calling

• check if it is safe for the victim to speak

• advise the victim that they may wish to delete any record of the call once the call is completed

• state that information will not be disclosed to the perpetrator

If the victim cannot be contacted after three separate attempts, this is taken to mean that the victim does not consent to receiving a service and no further information can be shared.

However, a review of WDVCAS conducted in January, found that 73% of clients were successfully contacted within five business days, showing that women were engaging, at least at the initial stage.

Women interviewed for the review said they valued being made aware of support services, many of which they had never heard of, or did not know how to access.

A referral from a GP should only include relevant information, such as the name, contact details and address of the victim, as well as the identified areas of risk.

“This is not talking about providing a whole clinical record,” says Professor Bateson.

Referrals also need to include the name of the perpetrator of the violence, and should indicate whether the woman is a non-native English speaker, needs a translator, or has a disability.

Shortcomings

The NSW Government has committed more than $53 million over four years to domestic violence services, but the reality is that this is unlikely to be sufficient to meet the demand.

The recent review of WDVCAS found that services were overwhelmed. There was a 60% increase in referrals at the start of Safer Pathways but no additional funding was allocated during the first six months.

The review said the limited capacity of services to offer medium to long-term support was of serious concern.

Ongoing support is necessary, as victims may never fully recover. A recent study2 of over 16,000 Australian women found that those who had experienced intimate-partner violence had poorer mental and physical health throughout their lifetime compared with their peers.

Another issue is that the new referral model appears to have been poorly communicated to GPs.

“A lot of the social services are a bit disconnected from healthcare,” says Dr McMullen.

“We are quite used to not knowing what is going on. It is an ongoing battle.”

Ms Le Breton did not have any statistics on how many GP referrals have been made since the pathway opened up two months ago.

This could, perhaps, be related to the apparent absence of the GP referral form on the NSW Government website. It was only after a day’s worth of bureaucratic gymnastics that The Medical Republic discovered that all GPs are required to email the NSW Department of Justice to obtain a referral form.

Community awareness of the prevalence of domestic violence has grown exponentially over recent years. The will to protect the women before they become statistics has never been stronger.

But a lack of confidence in new legislation could seriously damage collaboration between domestic-violence services and health professionals – and cost some women their lives.

Resources:

How to make referrals to Safer Pathways:

Email saferpathway@justice.nsw.gov.au to obtain a Safer Pathways Referral Form.

This form should be emailed to wdvcap@legalaid.nsw.gov.au for female victims and crp@justice.nsw.gov.au for male victims

References:

1. The Health Costs of Violence: Measuring the burden of disease caused by intimate partner violence 2004, VicHealth

2. PLOS One 2017, online June 5