While most diverticular disease is asymptomatic or mild, identifying higher risk patients with more severe disease can be crucial

Diverticular disease is a benign condition of the colon caused by symptomatic diverticulosis.

Diverticula are small pockets that bulge out of the colon, through its muscle wall.1, 2 In Western and industrialised nations, diverticulosis is commonly left-sided. However, in Asia it is predominantly right sided.3, 4 The incidence of diverticular disease is uncommon before the age of 30 but increases with age. Prevalence of diverticulosis is age-dependent with about 60% of patients over the age of 60 having diverticulosis. Of the patients with diverticulosis, only a quarter are symptomatic.1-3

Diverticulitis occurs when a diverticulum becomes infected and inflamed.

Diverticulitis can vary in severity.1, 2 Simple diverticulitis involves only inflammation of a colonic segment. Complicated disease includes perforation, obstruction, abscess formation, fistula and stricture formation.5

AETIOLOGY AND RISK FACTORS

The mechanism of diverticulosis is thought to be pressure-induced formation of outpouchings in the colonic mucosa at weak points where arterioles penetrate the circular muscle layer to supply the mucosa. There can also be accompanying muscle wall thickening and luminal narrowing.

The pathogenesis of diverticulitis has until recently been thought to occur when stasis or obstruction at the neck of the diverticulum leads to distension, overgrowth of pathogens and localised ischaemia.3, 6 More current studies from biopsy results in patients who have undergone surgery for diverticulitis suggest that diverticulitis is actually more of an inflammatory process rather than infective and the obstructive theory has been challenged.7

A low fibre diet, accompanied by a high intake of fat and red meat, is thought to lead to an increased risk of developing diverticulosis. Lack of fibre predisposes to constipation which results in harder stools that requires more pressure to push stools along the colon, possibly leading to the formation of diverticula. Contrary to popular belief, seeds and nuts are not associated with an increased risk of diverticulosis nor do they increase the risk of developing complications of diverticular disease. 3, 8, 9

CLINICAL MANIFESTATION

Most diverticulosis is asymptomatic. Diverticulosis can lead to abdominal cramping due to “gas trapping” in segments of the colon. There is an overlap between such symptoms in patients with a few diverticula and irritable bowel syndrome.

Abdominal pain is the chief complaint for patients with acute diverticulitis. The pain is typically localised to the left iliac fossa due to sigmoid colon involvement being the most common. However, a redundant sigmoid may result in pain in the suprapubic region and in rarer cases, the right iliac fossa. Right-sided pain is also more common in Asian patients.4, 6, 10

Other associated gastrointestinal symptoms include: nausea, vomiting and changes in bowel habits. Fever may or may not be present. A small proportion of patients also report urinary symptoms due to irritation of the bladder by an inflamed sigmoid colon.10

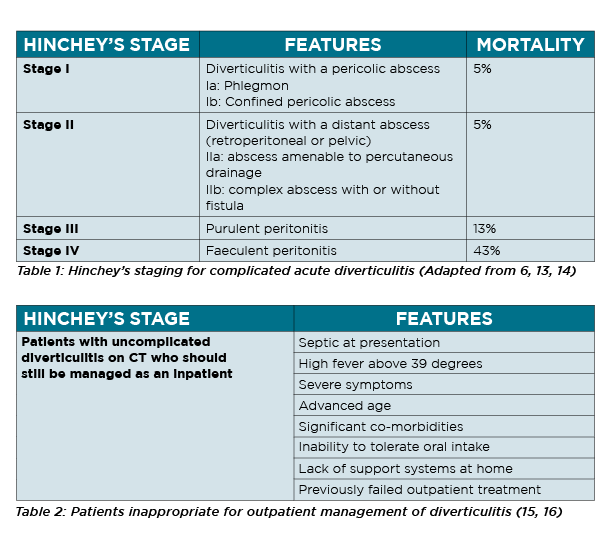

On examination, patients with more complicated disease may have localised peritonism or a palpable mass due to a phlegmon or peri-diverticular abscess.10 Inflammatory markers including white cell count (WCC) and C-reactive protein (CRP) aid in diagnosis. A CRP of less than 50mg/l is unlikely to be associated with complicated diverticulitis.11 (Table 1, P31). On the other hand, left-sided abdominal pain, a CRP greater than 50mg/l and absence of vomiting has a sensitivity of 98% for diagnosing diverticulitis.

If the location of pain is diffuse and the patient is diffusely tender when examined, serum lipase and liver function tests should be added to exclude other causes of severe abdominal pain.6,10

Computed tomography (CT) with intravenous and oral contrast is the best imaging modality in patients with suspected diverticulitis. In acute diverticulitis, CT is useful in confirming diagnosis and demonstrate the extent of extramural inflammation. It is also a useful tool to exclude other differential diagnoses.

Typical CT findings in acute diverticulitis include; localised bowel wall thickening, fat stranding and the presence of colonic diverticula. For acute diverticulitis, CT has a sensitivity and specificity of 94% and 99% respectively.

Patients with the first presentation of suspected diverticulitis should have a CT scan to confirm the diagnosis and evaluate the severity of the disease, which will guide management. In subsequent presentations, patients with significant symptoms or peritonism on examination should have a repeat CT to exclude a more severe manifestation of diverticulitis.12

Differential diagnoses for acute diverticulitis include perforated colorectal cancer, inflammatory bowel disease, infectious or ischaemic colitis and gynaecological causes in females.

Severity of complicated acute diverticulitis can be graded using the Hinchey’s criteria.13 (Table 1) A higher Hinchey stage is associated with more severe disease and higher associated morbidity and mortality.10

MANAGEMENT

Simple uncomplicated diverticulitis

The paradigm for management of simple uncomplicated diverticulitis has changed in the last decade. Most patients with uncomplicated diverticulitis can be managed as an outpatient with simple analgesia and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory agents. However, patients with a more complex medical background should still be managed as a hospital inpatient.5 (Table 2)

More recent understanding about the pathogenesis of diverticulitis has also challenged older management. Newer studies suggesting that diverticulitis is an inflammatory process has resulted in studies comparing treatment of simple uncomplicated diverticulitis without antibiotics versus mandatory antibiotics administration.

These studies suggested that antibiotics do not result in quicker resolution of symptoms, neither do they prevent complications. Hospital readmission rates and recurrence were also not higher than the traditional mandatory antibiotic administration group.17-21 The DIABOLO trial (2017) further pushed this boundary by showing that even for mild complicated diverticulitis (Hinchey Ia/Ib), antibiotics did not result in significant differences in outcome when compared to the antibiotics and inpatient admission arm.18 Despite these well-designed trials, most surgical units in Australia still use antibiotics as first line treatment for uncomplicated diverticulitis.

In summary, patients with uncomplicated diverticulitis can be managed in the outpatient setting if they present with reasonably mild symptoms and with good general health.

Complicated diverticulitis

Patients with more complicated disease (Hinchey II-IV) should be admitted to hospital for intravenous antibiotics with an initial period of gut rest. Patients should be monitored for their clinical trajectory and also the trend of their inflammatory markers. Patients with Hinchey II diverticulitis (distant or pelvic abscess) are usually still amenable to medical management alone with the radiological guided percutaneous drainage of larger abscesses (greater than 5cm). Hinchey III and IV diverticulitis usually require surgical intervention.

Surgical management

Surgical management for diverticulitis is usually reserved for patients with complicated, Hinchey III and IV diverticulitis. There are changes in the paradigm surrounding surgical management for diverticulitis with purulent peritonitis (Hinchey III). A review in 2010 suggested that laparoscopic lavage without bowel resection is a safe and feasible approach for Hinchey III diverticulitis. However, subsequent multicentre randomised trial recommended against laparoscopic lavage due to worse outcomes.23

In severe perforated or faeculent diverticulitis, surgery is required to remove the affected part of the bowel. There is, however, no clear evidence in the decision between performing a Hartmann’s procedure with the view of reversing the end colostomy versus resection with primary anastomosis. The ongoing DIVA arm of the LADIES trial will hopefully provide better information.22

Elective surgery for recurrent diverticulitis, on the other hand, requires a more individualised approach. Persistent symptoms, frequency of attacks, severity of attacks and patient’s immune status are some surrogates used to help decision making. Patients who are immunocompromised, such as those with chronic renal failure or long-term immunosuppression, should be considered for early elective resection as they are at a higher risk for developing complicated diverticulitis.

Patients who have complicated diverticulitis with associated obstruction or fistula formation should strongly be considered for elective resection.12 Should elective surgery be required, it should ideally take place four to six weeks after the acute attack as it significantly reduces the risk of anastomotic leak and also conversion to open surgery.24 Depending on the surgeon and patient suitability, colonic resection can be performed either via robotic assistance, laparoscopically or open.

Typically, the first episode of diverticulitis is the most severe and likely to lead to surgery. Generally, when a patient’s quality of life is compromised due to the frequency and severity of attacks and they are prepared to risk the small but significant risks of a resection, surgery is offered.

SURVEILLANCE

Association between diverticulitis and colon cancer have been reported by different authors with mixed results. In a recent large Danish-based cohort study, Mortensen et al (2017) found a significant association between diverticulitis and colon cancer.25 This is echoed by a previous Australian-based study which in addition found an even higher risk of cancer detection in patients with complicated diverticulitis. 26 Hence the current recommendation remains that in patients who have not had a colonoscopy within the last year of diverticulitis, surveillance colonoscopy six to eight weeks post-attack is indicated.

PREVENTION AND RISK REDUCTION

The evidence for high fibre diet reducing the risk of recurrent attacks of diverticulitis is weak. The American Gastroenterological Guidelines do suggest a fibre-rich diet in patients with acute diverticulitis if they are able to tolerate it. The evidence for avoiding nuts and popcorn in diverticulitis is however poor and patients should not be advised to avoid these foods.27

Smoking, alcohol and caffeine intake have also not been shown to increase one’s risk of recurrent diverticulitis.28 Obesity and high visceral fat are associated with a higher risk of complicated disease. Patients with lower physical activity were also at a higher risk.29, 30

CONCLUSION

Diverticular disease is a very common condition in Australia. Most disease is asymptomatic or mild and can be managed safely in an outpatient setting. General practitioners in the community play a very crucial role in identifying the higher risk patients who have more severe disease requiring specialist referral and likely inpatient management.

Dr Mark Muhlmann is a colorectal surgeon at Prince of Wales Public and Private Hospitals in Randwick, Sydney. He is also senior conjoint lecturer at University of NSW and surgical site director of training at Prince of Wales Hospital.

Zhen Hao (Eddy) Ang is a first-year general surgery registrar at Prince of Wales Hospital working towards a training position with the Royal Australasian College of Surgeons.

References:

1. CSSANZ. Diverticular Disease 2013 [Available from: https://cssanz.org/index.php/patients/diverticular-disease.

2. GESA. Diverticular Disease 2018 [Available from: http://www.gesa.org.au/resources/patients/diverticular-disease/.

3. McSweeney W, Srinath H. Diverticular disease practice points. Aust Fam Physician. 2017;46(11):829-32.

4. Chan CC, Lo KK, Chung EC, Lo SS, Hon TY. Colonic diverticulosis in Hong Kong: distribution pattern and clinical significance. Clin Radiol. 1998;53(11):842-4.

5. Siddiqui J, Zahid A, Hong J, Young CJ. Colorectal surgeon consensus with diverticulitis clinical practice guidelines. World J Gastrointest Surg. 2017;9(11):224-32.

6. O’Neill S, Ross P, McGarry P, Yalamarthi S. Latest diagnosis and management of diverticulitis. British Journal of Medical Practitioners. 2011;4(4).

7. Mora Lopez L, Ruiz-Edo N, Serra Pla S, Pallisera Llovera A, Navarro Soto S, Serra-Aracil X, et al. Multicentre, controlled, randomized clinical trial to compare the efficacy and safety of ambulatory treatment of mild acute diverticulitis without antibiotics with the standard treatment with antibiotics. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2017;32(10):1509-16.

8. Aldoori WH, Giovannucci EL, Rimm EB, Wing AL, Trichopoulos DV, Willett WC. A prospective study of diet and the risk of symptomatic diverticular disease in men. Am J Clin Nutr. 1994;60(5):757-64.

9. Strate LL, Liu YL, Syngal S, Aldoori WH, Giovannucci EL. Nut, corn, and popcorn consumption and the incidence of diverticular disease. JAMA. 2008;300(8):907-14.

10. Jacobs DO. Clinical practice. Diverticulitis. N Engl J Med. 2007;357(20):2057-66.

11. Kaser SA, Fankhauser G, Glauser PM, Toia D, Maurer CA. Diagnostic value of inflammation markers in predicting perforation in acute sigmoid diverticulitis. World J Surg. 2010;34(11):2717-22.

12. Vennix S, Morton DG, Hahnloser D, Lange JF, Bemelman WA, Research Committee of the European Society of C. Systematic review of evidence and consensus on diverticulitis: an analysis of national and international guidelines. Colorectal Dis. 2014;16(11):866-78.

13. Hinchey EJ, Schaal PG, Richards GK. Treatment of perforated diverticular disease of the colon. Adv Surg. 1978;12:85-109.

14. Schwesinger WH, Page CP, Gaskill HV, 3rd, Steward RM, Chopra S, Strodel WE, et al. Operative management of diverticular emergencies: strategies and outcomes. Arch Surg. 2000;135(5):558-62; discussion 62-3.

15. Alonso S, Pera M, Pares D, Pascual M, Gil MJ, Courtier R, et al. Outpatient treatment of patients with uncomplicated acute diverticulitis. Colorectal Dis. 2010;12(10 Online):e278-82.

16. Etzioni DA, Chiu VY, Cannom RR, Burchette RJ, Haigh PI, Abbas MA. Outpatient treatment of acute diverticulitis: rates and predictors of failure. Dis Colon Rectum. 2010;53(6):861-5.

17. Chabok A, Pahlman L, Hjern F, Haapaniemi S, Smedh K, Group AS. Randomized clinical trial of antibiotics in acute uncomplicated diverticulitis. Br J Surg. 2012;99(4):532-9.

18. Daniels L, Unlu C, de Korte N, van Dieren S, Stockmann HB, Vrouenraets BC, et al. Randomized clinical trial of observational versus antibiotic treatment for a first episode of CT-proven uncomplicated acute diverticulitis. Br J Surg. 2017;104(1):52-61.

19. Estrada Ferrer O, Ruiz Edo N, Hidalgo Grau LA, Abadal Prades M, Del Bas Rubia M, Garcia Torralbo EM, et al. Selective non-antibiotic treatment in sigmoid diverticulitis: is it time to change the traditional approach? Tech Coloproctol. 2016;20(5):309-15.

20. Isacson D, Thorisson A, Andreasson K, Nikberg M, Smedh K, Chabok A. Outpatient, non-antibiotic management in acute uncomplicated diverticulitis: a prospective study. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2015;30(9):1229-34.

21. Mali JP, Mentula PJ, Leppaniemi AK, Sallinen VJ. Symptomatic Treatment for Uncomplicated Acute Diverticulitis: A Prospective Cohort Study. Dis Colon Rectum. 2016;59(6):529-34.

22. Nally DM, Kavanagh DO. Current Controversies in the Management of Diverticulitis: A Review. Dig Surg. 2018.

23. Schultz JK, Yaqub S, Wallon C, Blecic L, Forsmo HM, Folkesson J, et al. Laparoscopic Lavage vs Primary Resection for Acute Perforated Diverticulitis: The SCANDIV Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2015;314(13):1364-75.

24. Reissfelder C, Buhr HJ, Ritz JP. What is the optimal time of surgical intervention after an acute attack of sigmoid diverticulitis: early or late elective laparoscopic resection? Dis Colon Rectum. 2006;49(12):1842-8.

25. Mortensen LQ, Burcharth J, Andresen K, Pommergaard HC, Rosenberg J. An 18-Year Nationwide Cohort Study on The Association Between Diverticulitis and Colon Cancer. Ann Surg. 2017;265(5):954-9.

26. Lau KC, Spilsbury K, Farooque Y, Kariyawasam SB, Owen RG, Wallace MH, et al. Is colonoscopy still mandatory after a CT diagnosis of left-sided diverticulitis: can colorectal cancer be confidently excluded? Dis Colon Rectum. 2011;54(10):1265-70.

27. Stollman N, Smalley W, Hirano I, Committee AGAICG. American Gastroenterological Association Institute Guideline on the Management of Acute Diverticulitis. Gastroenterology. 2015;149(7):1944-9.

28. Aldoori WH, Giovannucci EL, Rimm EB, Wing AL, Trichopoulos DV, Willett WC. A prospective study of alcohol, smoking, caffeine, and the risk of symptomatic diverticular disease in men. Ann Epidemiol. 1995;5(3):221-8.

29. Dobbins C, Defontgalland D, Duthie G, Wattchow DA. The relationship of obesity to the complications of diverticular disease. Colorectal Dis. 2006;8(1):37-40.

30. Jeong JH, Lee HL, Kim JO, Tae HJ, Jung SH, Lee KN, et al. Correlation between complicated diverticulitis and visceral fat. J Korean Med Sci. 2011;26(10):1339-43.