CALD communities vary greatly in their attitudes to covid, showing the peril of taking a one-size-fits-all approach.

GPs and other health professionals should be prepared to play a key role in re-engaging patients from non-English-speaking households as covid hits vulnerable communities, research suggests.

In New South Wales, western and southwestern Sydney – which both have a relatively high level of culturally and linguistically diverse (CALD) residents – are the hardest hit in the outbreak, yet have lower vaccination rates than other areas of the state.

Just last week, NSW Health Minister Brad Hazzard seemed to indicate that culturally diverse communities were at least partly to blame for the ongoing rise in infections.

“There are other communities and people from other backgrounds who don’t seem to think that it is necessary to comply with the law and who don’t really give great consideration to what they do in terms of its impact on the rest of the community,” he said.

However, according to University of Sydney public health researcher Dr Julie Ayre, there is a high willingness to comply among Sydney’s multicultural residents – but the right communication channels must be leveraged.

Dr Ayre and colleagues recently collected data on health literacy and attitudes toward covid from about 700 people, all of whom lived in western Sydney, south western Sydney or the Blue Mountains and primarily spoke a language other than English.

Their findings were presented at a webinar hosted by the Western Sydney Local Health District earlier this week.

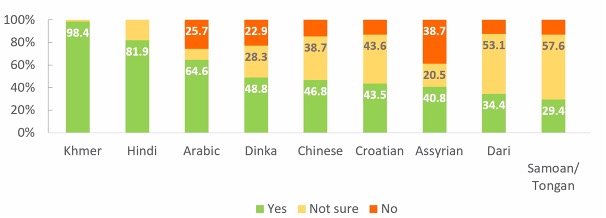

The researchers focussed on nine language groups representing established and emerging communities in the region: Arabic, Assyrian (Iraq), Chinese, Croatian, Dari (Afghanistan), Dinka (South Sudan), Hindi, Khmer and Tongan/Samoan.

All data was collected earlier this year, but before the current outbreak spread beyond Sydney’s eastern suburbs.

Although there were uniformly high levels of covid knowledge and self-reported infection-prevention behaviours across language groups, there was a marked divergence in how each group perceived covid-related risk.

The three groups which reported the lowest perceived risk – Arabic, Chinese and Assyrian – also made up three of the four groups who found it most difficult to access covid information in English.

Interestingly, the fourth group which experienced difficulty accessing English covid information was Dari speakers, who had the highest perceived risk.

Despite their high perceived risk, Dari speakers also expressed some of the highest levels of uncertainty around the vaccine, while Khmer speakers – who also indicated a very high perception of risk – recorded the highest level of certainty.

“There was really high variability across language groups [in terms of survey responses], and I think that speaks to the need to really specifically target different language and cultural groups in order to be able to support them better,” Dr Ayre said during the webinar.

“We consistently found that people found it harder to find covid-19 information if they had lower English language proficiency, if they were older and if they had low health literacy.”

Dr Ayre’s survey also measured where people turned to for information.

While 23% of all respondents indicated they got official news from the government website, 34% said they looked to health professionals such as GPs.

Older people tended to rely more heavily on friends and family living in Australia, their local community or overseas information.

“We need to leverage the diverse communication channels that people in these communities are actually using to find health information,” Dr Ayre said.

“We really want to strengthen and support community-led and on-the-ground health professional communication strategies.

“Community leaders, community champions and health professionals are all really, really important in being able to help engage with the community and provide information in a really timely way.”

The community profiles developed by Dr Ayre and colleagues are available on the Health Literacy Hub website.