COVID-19 is causing discontinuities in the care of chronic illnesses, and for osteoporosis patients that has real consequences.

COVID-19 is creating obvious disconnects for many patients with a chronic illness that in normal times would require regular GP and allied health professional attendances.

MBS data suggests that throughout April and May face-to-face consultations throughout the entire GP network in Australia may have dropped by as much as 50% from the same time last year, a stat that clearly makes continuity of care for any chronic condition more difficult [1]. In the same time, telehealth consultations have risen sharply to the point in May where they probably make up more than 50% of entire consults and to some degree might be plugging a lot of the continuity hole.

But in the case of some chronic illnesses and care plans, a break in face-to-face continuity can be very damaging to a patient, even in the short term.

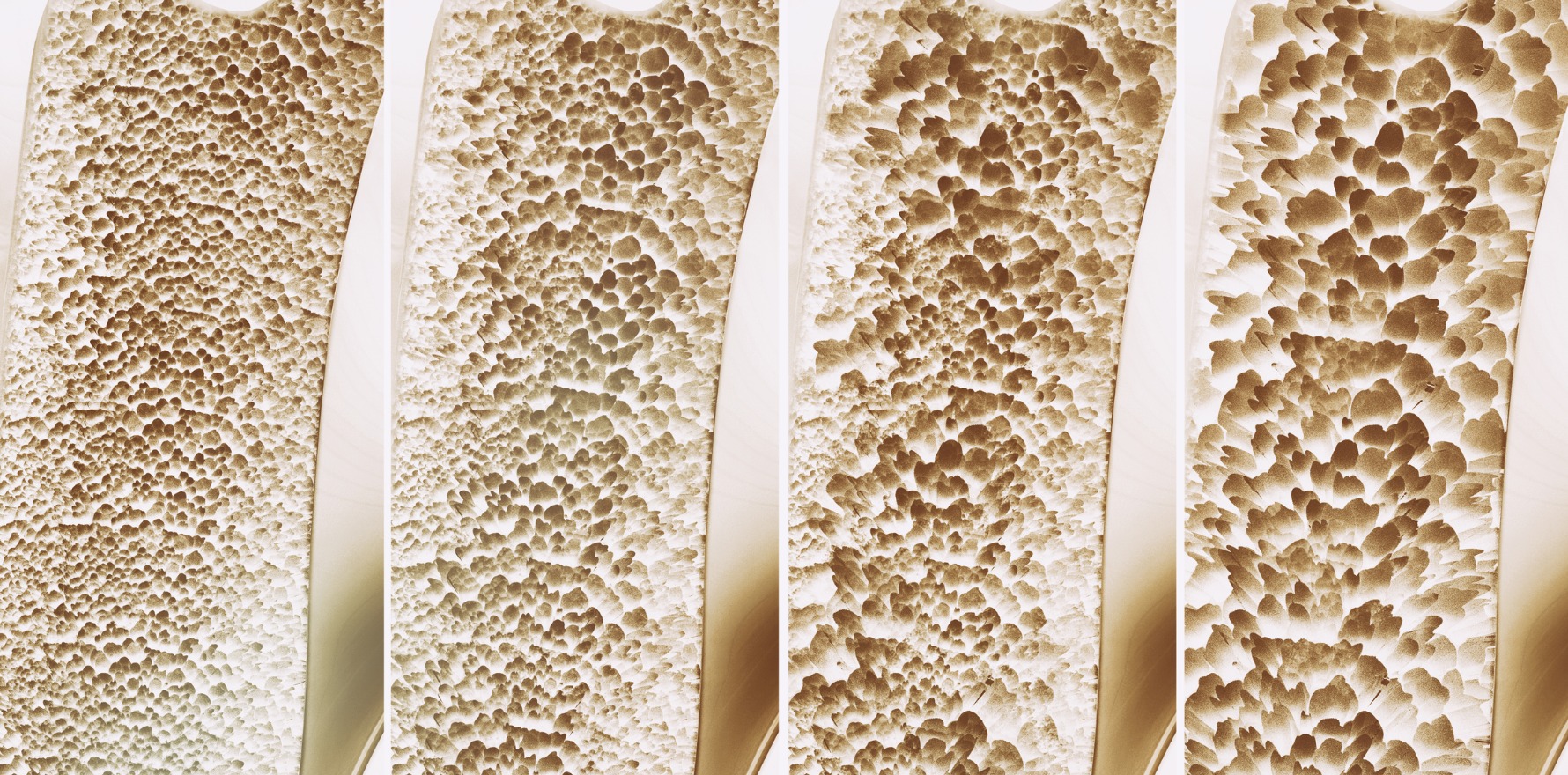

One of the trickiest conditions might be osteoporosis because these days up to 80% of all osteoporosis patients over 50 years of age are on a six-monthly injection of the biological agent denosumab (brand name Prolia). Denosumab may be initiated by either a specialist or a GP but after that injection and ongoing monitoring are generally managed by the patient’s GP. Once you are on denosumab it is usually recommended that you stay on it for life, unless you have any particular issues with it. If you go off it for any reason, then serious issues can ensue within weeks if the patient isn’t put on a course of biphosphonates to protect the patient from a rapid reversal of bone mineral density (BMD). As with a blood pressure drug, once you stop taking denosumab, the protective effect of the drug disappears almost immediately exposing a patient to fracture risk.

Once all those osteoporosis patients on denosumab would have been on a daily, weekly or monthly oral bisphosphonate – risedronate (Actonel) or alendronate (Fosamax ) – or even a bi-yearly biphosphonate injection – zoledronic acid (Aclasta). Bisphosphonates act quite differently to denosumab and build up protection over time which is not lost for some time after treatment is ceased.

Of those remaining 20% of patients who are on bisphosphonates in Australia COVID-19 is far less of a problem because a telehealth call followed by an online script is enough to maintain the treatment until continuity can be resumed as before.

Of the many biphosphonates available these days, Actonel EC (enteric coating) once a week, is generally preferred because the patient does not need to fast, and the treatment can be taken with food, unlike all other bisphosohonates.

The key emerging problem with denosumab during COVID-19 is that so many patients and GPs have been disrupted in their normal patterns during the pandemic it is likely that many patients are missing their regular denosumab injection.

Eighty percent of osteoporosis patients on a bone density treatment are on denosumab because it is generally seen these days as slightly more effective, and as safe as oral bisphosphonates [2] so long as you keep them on the treatment and make sure patients go on biphosphonates if taken off.

If a six-monthly denosumab injection has to be postponed by anything more than four to five weeks, Osteoporosis Australia is recommending that GPs organise for their patients to switch to bisphosphonates as soon as possible, until continuity of care, especially face to face care, is restored [3]. Switching, as mentioned above, is easy via a telehealth consult.

Professor Peter Ebeling, head of the Department of Medicine in the School of Clinical Sciences at Monash Health, says experts are increasingly worried by the possible interruption of GP care for their osteoporosis patients during COVID-19 because BMD declines so rapidly following cessation of the treatment.

“As well as the bone density going down, there is an increased risk of spinal fracture, if they cease treatment,” he tells TMR, citing the long-term FREEDOM study and the FREEDOM Extension Study [4], in which people who for any reason stopped denosumab treatment started to have spinal fractures after only five weeks.

The fact it takes only five weeks for this potential danger to appear is important for GPs to understand in the current COVID-19 environment of treatment, he says.

Professor Ebeling, who is also the medical director of Osteoporosis Australia (OA), told patients and doctors in the organisation’s May newsletter that it was vital that patients on denosumab received their six-monthly denosumab injection throughout COVID-19. Should they miss it by more than four weeks, GPs should initiate bisphosphonates immediately and keep their patients on this regime until both patient and doctor were comfortable that they could restart their denosumab injections [5].

“When the COVID pandemic is over, patients can be swapped back to the denosumab with the first injection at the time their next oral tablet is due,” he wrote.

Some confusion started to emerge throughout May and June with some doctors taking the advice and merging it with a recent OA position statement on osteoporosis, which says that once you cease denosumab for any reason, “transition to an oral bisphosphonate for at least 12 months is recommended”.

Clarifying this, Professor Ebeling says the wording of the OA guideline did not anticipate COVID-19 and was meant for any situation in which a patient was stopping denosumab for good. He says it is fine to restart denosumab at any time so long as there has been bisphosphonate treatment in the meantime, so that BMD is not lost.

Professor Ebeling worries that because the disruption is so extended, and there isn’t an end in sight yet – especially in Victoria – that some of the continuity systems used by GPs to make sure nothing is missed with their chronic care patients might start to break down.

Key among those systems is the GP’s desktop patient management system, which will keep automatic reminders for both the GP and a practice administrator if the practice is large. Nearly all PMS systems for GPs are on their desk in their practice, and many may have lost access during COVID-19. In addition, other interruptions to their normal working cycle, such as gearing up for telehealth rapidly and fitting practices out for patient safety, are likely to have created some gaps in the normal reminder systems.

According to a study published recently in the open-access online journal BMC Family Practice, of the 12.4% of patients over the age of 50 diagnosed with osteoporosis only a quarter were prescribed any osteoporosis treatment [6]. The same study found that more than 80% of the patients who were prescribed denosumab and ceased treatment were not subsequently taking bisphosphonates, as recommended by OA.

The study suggests that quite apart from the issues created for osteoporosis patients by COVID-19, the condition is probably significantly underdiagnosed and treated in Australia anyway, a problem likely exacerbated by a failure in the majority of patients who cease denosumab to transition to a course of antiresorptive therapy in the form of biophosphonates. Both situations now need to carefully addressed.

- MBS data April, May 2020 (http://medicarestatistics.humanservices.gov.au/)

- Lyu H, Jundi B, Xu C, et al J Clin Endocrinol Metab. doi: 10.1210/jc.2018-02236

- OA Australia, Position Statement on Management of Osteoporosis, April 2020

- The Lancet, Diabetes-endocrinology, May 22, 2017, http://10.1016/s2213-8587(17)30138-9

- Osteoblast, OA, Autumn 2020, p2

- Naik-Panvelkar et al, BMC Family Practice (2020) 21:32