The global digital giants all have their eyes on the healthcare sector, but will any of them make a meaningful impact?

Global technology companies are the new masters of our everyday universe, so it’s natural that they would want to stake a claim in the health sector. But digital disruption has been late to healthcare and, in some instances, the seemingly brilliant strategy and thinking behind the rise of the tech giants has led to spectacular failures. One of Facebook’s forays into the sector has resulted in shock, anger, and a new level of questioning at just how powerful and dangerous these global platforms can be. But where there is bad, there is clearly also some good. Here we review the progress of six global digital giants in making a meaningful and useful impact in the health sector.

The words ‘Facebook’ and ‘large-scale psychological experiment’ do not sit well together. The public backlash to Facebook’s experiment on around 700,000 non-consenting users in 2014 was so extreme that the company was forced to issue an explanation.

The researchers manipulated the number of positive and negative posts in news feeds to see if they could alter the emotional state of individuals. Users implicitly agreed to participate in research through Facebook’s Terms of Use, but Facebook acknowledged that a more transparent and ethical process was needed.

Facebook did not provide a detailed response to TMR’s queries about its plans to expand into health. But the social media mega-giant appears to have more to offer the health industry than converting its users into lab rats.

With 1.94 billion active users, Facebook connects 27% of the world’s population. Many health charities, patient advocate groups and public health groups are already using the Facebook platform to connect with millions of people. In Australia, Facebook is the platform of choice for GPs Down Under, arguably our most successful and influential GP social media and learning platform.

Another success was the ALS ice bucket challenge, which ran rampant on Facebook in 2014, with 17 million videos uploaded and $117 million raised for ALS research.

Other health initiatives using the Facebook platform include Social Blood, which connects patients to blood products, and Genes for Good, a genetics research project by the University of Michigan.

Reuters revealed rumours about a Facebook project to create patient communities in 2014. Nothing has been heard since but similar projects, such as PatientsLikeMe, demonstrate that patients are willing to reach out to other patients online.

A surprise success story for Facebook occurred in 2012 when the company released a timeline feature that would allow users in the US and the UK to identify themselves as organ donors. If a user selected ‘‘organ donor’’ on their profile, they were directed to their local donor registry and their Facebook friends were made aware of the change. A study later published in the American Journal of Transplantation reported a 21-fold increase in the daily rate of organ donation registration on the first day of the Facebook roll-out.

Apple

The core philosophy of Apple’s health division is to empower the people who know how to solve health problems, a spokeswoman told TMR. The slab of glass in people’s pockets should serve as a window into constellations of applications, of which only a few are developed in-house.

The company has three main ways of stirring external creativity. The first is ResearchKit, a software framework for medical researchers. This platform has been used to launch the largest Parkinson’s study in history through the mPower app. The Autism & Beyond app, also developed with ResearchKit, is using facial recognition algorithms to identify early signs of autism in children.

“The sheer number of iPhone users around the globe means that apps built on ResearchKit can enroll participants and gather data in bigger numbers than ever,” Apple said.

Secondly, Apple’s CareKit provides a framework for developers to build apps that help people manage their personal well-being. The company’s HealthKit is an extension on this concept. It allows developers to integrate the activity-tracking features of Apple Watch with their own apps.

HealthKit, not to be confused with a local clinical software management start-up of the same name, is being developed in partnership with the Mayo Clinic and Epic, which currently has a 25% market share of EMRs in the US. Pundits have speculated that this alliance could potentially solve the problem of “health metric silos” by giving Apple access to a large chuck of EMRs, overcoming the issues faced by Google and Microsoft.

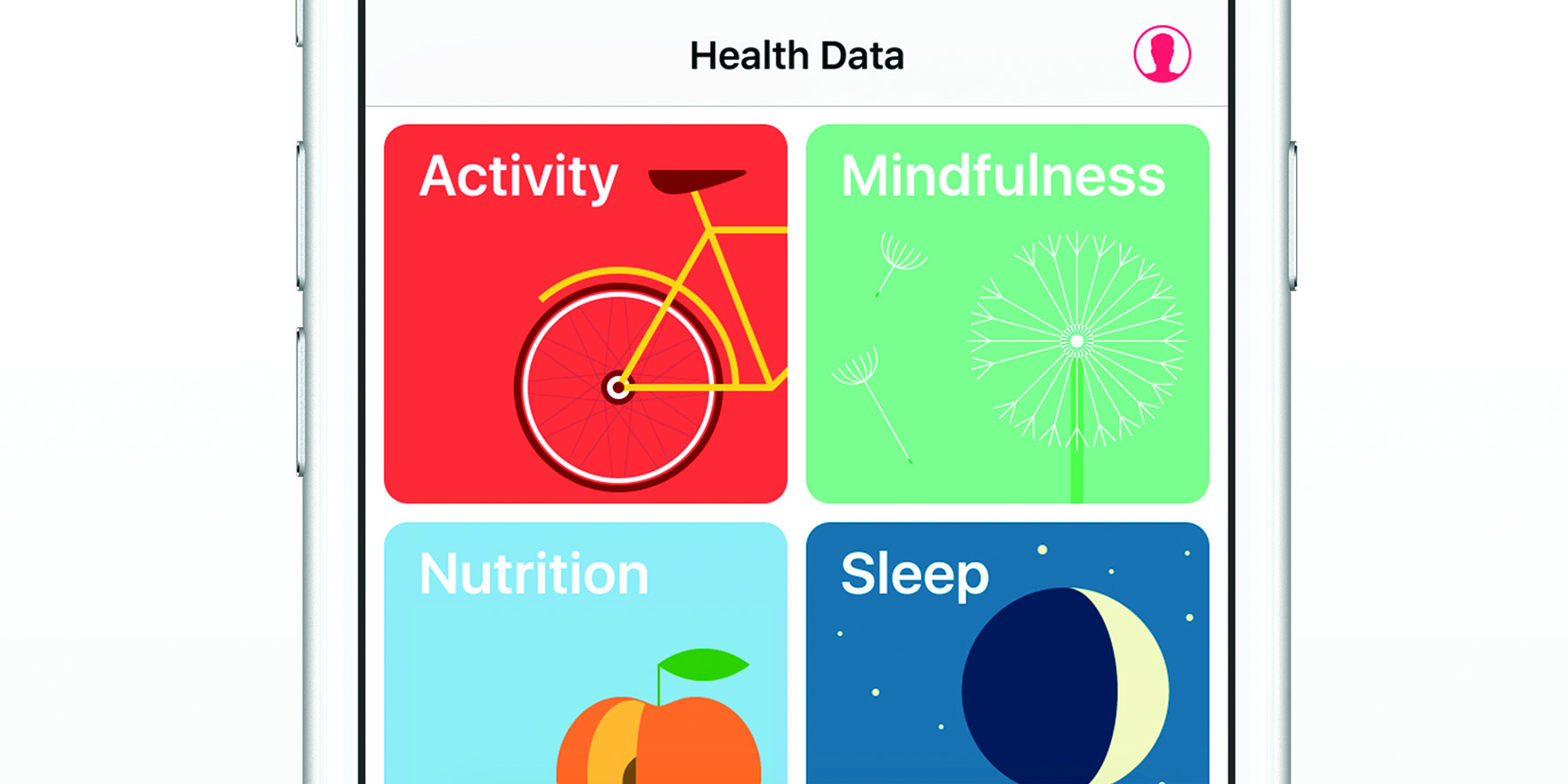

The final jewel in Apple’s health crown is the Health app, which consolidates health data from iPhone, Apple Watch and third-party apps. The app designates each metric into four categories: Activity, Sleep, Mindfulness and Nutrition.

With a market value surpassing $600 billion, Google is the second-largest company in the world, behind Apple. But despite its vast treasure chest, Google has struggled to gain a firm foothold in the health technology arena.

Google Health, a free online health platform, flatlined only four years after launching in 2008. On its blog, Google said it had been adopted among tech-savvy patients and fitness enthusiasts. “[But] we haven’t found a way to translate that limited usage into widespread adoption in the daily health routines of millions of people,” the company said.

The post-mortem by tech analysts at the time concluded that Google’s application failed to piece together the fragmented healthcare system, instead relying on patients to chase individual bits of information. In the end, the benefits of using the platform just weren’t worth the effort.

Health has continued to be a difficult area for Google, with controversy breaking out over its data sharing arrangement with NHS last year. Google’s AI company DeepMind obtained 1.6 million NHS patient records to test a smartphone app, Streams, for monitoring people with kidney disease. The records contained sensitive information about abortions, HIV status and overdoses over the past five years.

The UK government’s watchdog, the National Data Guardian, found that the record sharing was completed on an “inappropriate legal basis” and that permission should have been sought from patients.

Meanwhile, DeepMind is planning a new tool that could process data from millions of patients to detect septicaemia. It is also developing an algorithm to distinguish healthy and cancerous tissue from CT and MRI scans, and a program that will detect macular degeneration and diabetes-related sight loss in eye scans.

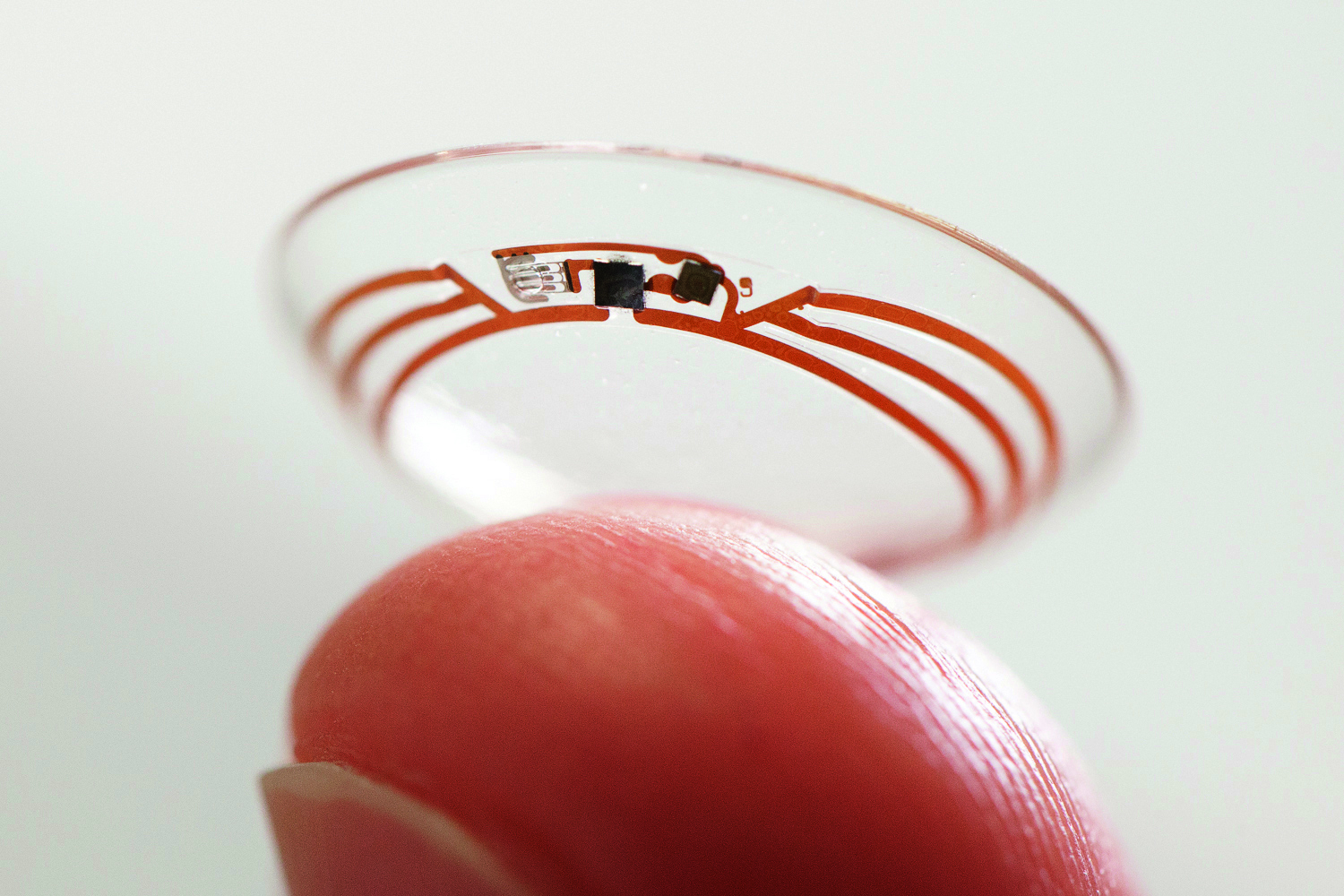

Google’s research projects include testing a smart contact lens that can measure glucose levels in tears with a wireless chip. The prototype, developed by Google’s life sciences department, Verily, in partnership with Novartis’ Alcon eye care division, might someday be a new way for people with diabetes to manage their disease, Google said.

One in 20 Google searches are health-related. To better answer these health questions, Google launched its Health Cards in the US in 2015, expanding to Australia in February this year. The cards display quick facts about a myriad of diseases and conditions, which have been checked for accuracy by doctors. The cards received a lukewarm response from Australian health professionals, who queried Google’s motivations and expressed doubts about the usefulness of the product.

Microsoft

Microsoft stepped into the consumer health industry with the launch its personal health records system, HealthVault, in 2009. A flurry of activity around the same time saw a number of competitors release similar platforms, with Google Health going to market in 2008.

But the concept of personally entering health data, and uploading medical imaging, x-rays, ultrasounds, MRIs, and insurance information didn’t catch on. People were not motivated to use Google’s service and the company pulled the plug on the project in 2012, allowing users to transfer data across to Microsoft’s HealthVault.

HealthVault is still alive and kicking today, although there are some signs that consumers continue to take little interest. For instance, Fitbit cancelled its arrangement with Microsoft last year and Microsoft also recently dropped the HealthVault app from the Microsoft Phone Store.

The company tried a different tack with the Microsoft Health app, which launched on Android, iOS and Windows Phone in 2014. This platform takes information about steps, calories, sleep quality and heart rate from Microsoft Band, a wearable fitness tracker, and analyses data using the Microsoft Intelligence Engine.

Much of Microsoft’s health business exists in the B2B space, although the company abandoned its first venture. Microsoft’s Health Solutions Group was folded into a joint venture with General Electric six years after launching in 2005. The revived healthcare analytics company, Caradigm, appears to be doing well, boasting a customer base of over 1,500 hospitals.

The bread and butter of Microsoft’s health arm now leverages off existing capabilities. Just this month, Bendigo Hospital in Victoria announced that it was deploying Window’s touchscreen devices to allow clinicians to access the cloud computing platform, Azure, from any location.

The next step is for patients to take technology with them when they leave the hospital setting, allowing for ongoing monitoring.

Microsoft is also entering the telehealth space with Skype for Business being used to connect rural hospitals in Australia to urban specialists and to underpin a new Australian built telehealth start-up, Welio.

Other research projects by groups partnering with Microsoft include intelligent chatbox technology to triage patients and speech recognition to replace manual data entry by doctors.

Microsoft is also at the cutting edge of health technology with an augmented reality headset called Microsoft HoloLens being used by CAE Healthcare to create interactive anatomy classes for medical students.

The company is also tackling diabetic retinopathy through its IRIS retina exam. This consists of an automated imaging system which sends information to a specialist at another location who then makes a recommendation.

In all its health enterprises, Microsoft aims to do more with the existing data within the health system, says Mr Nic Woods, health lead for Microsoft Australia. “That is making that transition now from being systems of record to becoming systems of insight and intelligence.”

IBM

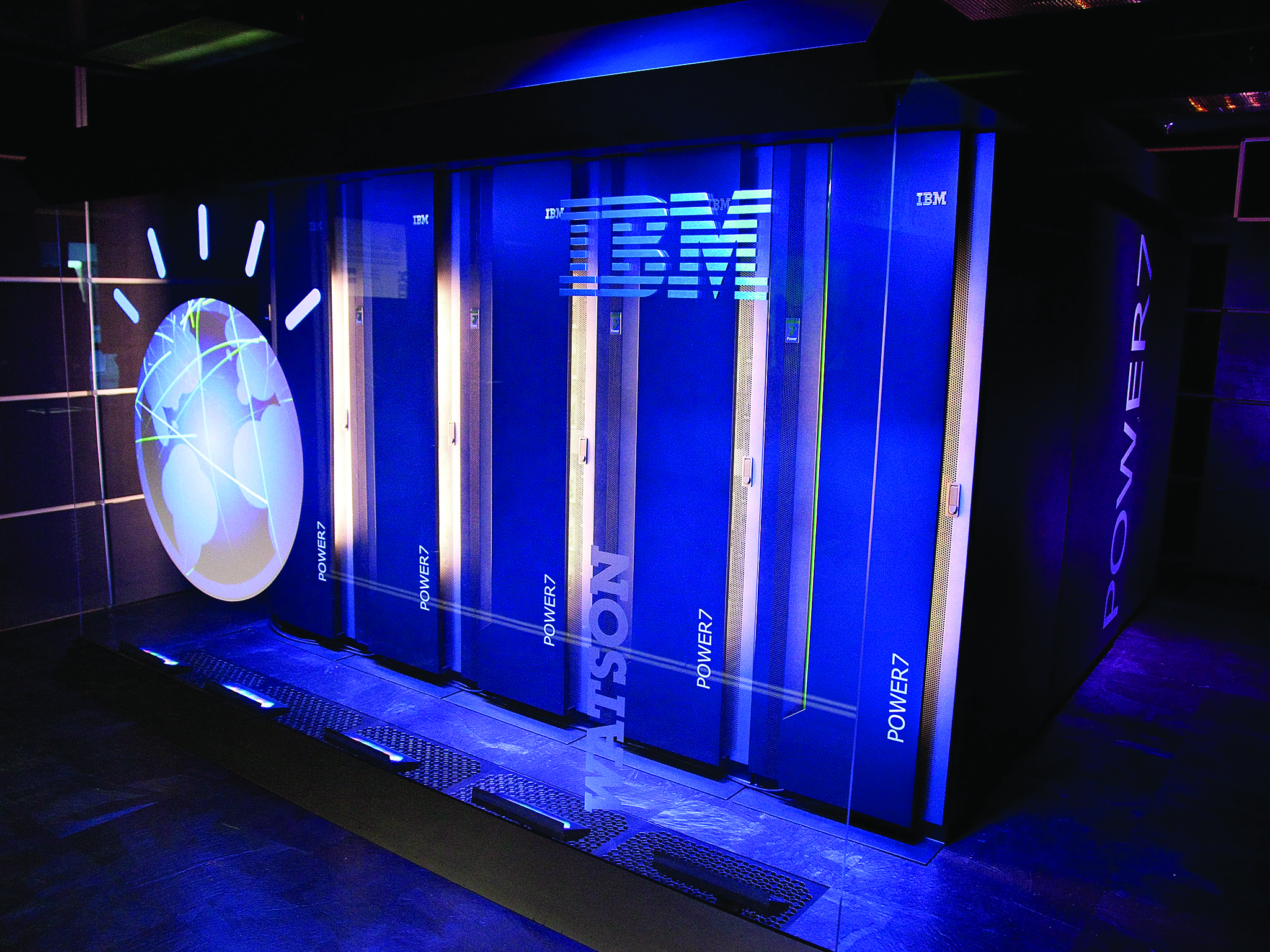

Health was the first industry that IBM pointed its supercomputer Watson towards. Watson’s ability to digest more data than any human makes it a neat solution to the health industry’s biggest problem: information overload.

“The massive amounts of data, literature and medical imaging that exists became increasingly challenging for the industry to process,” Dr Joanna Batstone, vice president and lab director at IBM Research Australia, told TMR. “It is simply not humanly possible to read through this amount of information.”

IBM company launched a dedicated business unit called Watson Health in April 2015. It now has 12 research labs around the world, including one in Australia.

Watson Oncology is a cognitive computing system designed to help clinicians make decisions about lung and breast cancer treatments. It has ingested nearly 15 million pages of medical content on cancer, including more than 200 textbooks and 300 journals. Watson mines this data to match specific patients to the treatment for similar patients.

IBM Watson Genomics chews up 10,000 scientific articles and 100 new clinical trials every month. Partnering with Quest Diagnostics, this system identifies highly personalised cancer treatments by analysing the mutations specific to individual patients. Watson can currently identify pair substitutions, insertions and deletions in 34 genes – and plans to expand this to 400 genes this year.

But like Facebook and Google, even Watson, with its intense focus on solving intimate health problems has run aground on the complexity that is health. Recently, IBM Watson suffered scathing criticism in a project to assist the Texas-based MD Anderson Cancer Centre. After spending more than $US62m on Watson AI to assist in diagnosis, auditors concluded that Watson’s Oncology Expert Advisor had done little or nothing to progress the productivity of the group and IBM subsequently lost this prestigious contract.

But IBM is succeeding in other areas. Researchers trained a computer to identify skin cancers using a dataset of 900 dermoscopic images with 76% accuracy (up from 70% with the naked eye). The same is being done for diabetic retinopathy. IBM technology was trained using more than 35,000 eye images to identify lesions and assess both the presence and severity of the disease, with an accuracy of 86%.

IBM’s real-time streaming analytics is being used by Emory University Hospital in the US for advance predictive medicine for ICU patients.

Similar cognitive analytics was also used by IBM researchers to predict hypoglycemic events in 600 anonymous patient cases up to three hours before the onset of symptoms. The data was collected from patients with diabetes using Medtronic insulin pumps and glucose monitors, which measure real-time glucose levels using electrodes inserted under the skin.

IBM is developing an app called Sugar.IQ, which will use continuous glucose monitoring data to give patients with diabetes insights into how their glucose levels are associated with diet or activity.

Samsung

Samsung’s health business stretches back to the 1980s, with the launch of an affiliated medical technology company Samsung Medison. This company specialises in producing ultrasound systems, portable CT, in-vitro diagnostics and digital radiography.

More recently, Samsung has branched into consumer health products. The S Health app launched in 2012, which rebranded as Samsung Health in April this year, allows users to monitor weight, blood pressure, food intake and blood sugar levels from their phone. Samsung launched its wearable fitness device Gear Fit in 2014, with the Gear Fit 2 coming out in June last year.

With an eye to moving further into this large and growing industry, the company also announced a $50 million investment pool to fund digital health start-ups in 2014.

In Sydney, Samsung is currently trialling ‘distraction therapy’ for patients undergoing chemotherapy. In partnership with Chris O’Brien Lifehouse, Samsung hopes its virtual reality technology will help ease psychological stress.

Samsung Australia is also teeing up with retirement homes to trial personalised tablets that simplify communication tools such as Facebook, Skype, and email for older people. “[This project is] helping the elderly to get the benefits without having to understand or master the underlying technology,” Samsung said.

Samsung launched a trial in aged care of a home sensor, SmartThings, in Australia last year. The technology alerts healthcare providers when abnormal activity is detected in or around the home.