The presence in warrior graves of small spoons suggests so.

Your correspondent is fresh from covering the NSW Drug Summit last week (see here, here, here, here and here), which a fellow attendee described as less like watching a sausage being made than watching the government spend a lot of money pretending to make a sausage.

Amid the political hysteria reliably generated by the issue of recreational drugs, it’s salutary to remember that substance use for non-medicinal purposes is far from a recent or aberrant human behaviour (even if the line between medicinal and recreational is very smudged).

While narcotic use in Ancient Greece and Rome is well documented, it’s been assumed that people outside these civilisations were confined to booze.

Now we learn that those on the fringes of the Roman empire may also have used a variety of stimulants, for ritual purposes or to enhance their performance in resisting the imperial armies.

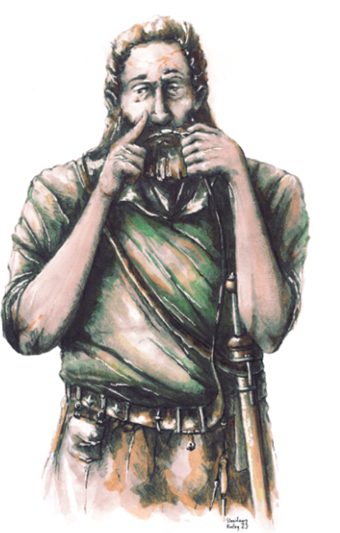

What’s the clue? Spoons: hundreds of small spoons of varying materials and dimensions found in warriors’ graves in what are now Scandinavia and eastern Europe, and evidently worn on belts as part of their battle kit.

“The indicated objects could have been used in an excellent way to dose stimulants,” write the German and Polish authors.

Published in Praehistorische Zeitschrift, the paper even includes an artist’s impression of a Germanic warrior using such a spoon in such an excellent way.

By stimulants they don’t mean the uppers of today, but powdered psychotropic substances derived from poppies (the ancient Greeks are credited with developing the technique of extracting opium from the milky juice, knowledge that spread with the expansion of the Arab empire); cannabis sattiva; hops (used by the Romans to treat liver disease and digestive disorders and “as a blood purifier” before they put it in beer); hallucinogenic nightshade plants; henbane; and fungi such as ergot.

The spoons’ context, accompanied by weaponry, allow the authors to hypothesise “that this utensil was a common part of a warrior’s armour, and from here it is close to concluding that pharmacological stimulation of warriors in the face of stress and exertion was the order of the day”.

Given the Romans’ unstinting violence and brutality, even the Minns government might find it hard to begrudge these warriors a pick-me-up.

Send restorative story tips to penny@medicalrepublic.com.au.