What role GPs can play in the overall management and monitoring of this challenging condition

Chronic pancreatitis is an irreversible and progressive disorder of the pancreas characterised by inflammation, fibrosis and loss of acinar and islet cells.

The condition classically causes chronic pain and can lead to endocrine and exocrine insufficiency as it progresses. Most commonly, patients with chronic pancreatitis present with abdominal pain, which often leads to a misdiagnosis of acute pancreatitis, especially in the early stages.

As a chronic disease, chronic pancreatitis has significant health and socioeconomic consequences for patients. It is a challenging disease to diagnose and manage and most patients remain symptomatic despite treatments. There are no effective therapies to reverse or halt the spread of disease.

The GP plays an integral role in the overall management and monitoring of the disease. Better recognition of the risk factors and conditions associated with chronic pancreatitis can lead to an earlier diagnosis and coupled with a multidisciplinary approach to treatment, ultimately reduce complications.

PREVALENCE & AETIOLOGY

There is limited data available regarding the prevalence of chronic pancreatitis in Australia. Other developed countries have an estimated annual incidence rate of 5-12/100,000 for the development of chronic pancreatitis. The prevalence of chronic pancreatitis is estimated to be 50/100,000 people.

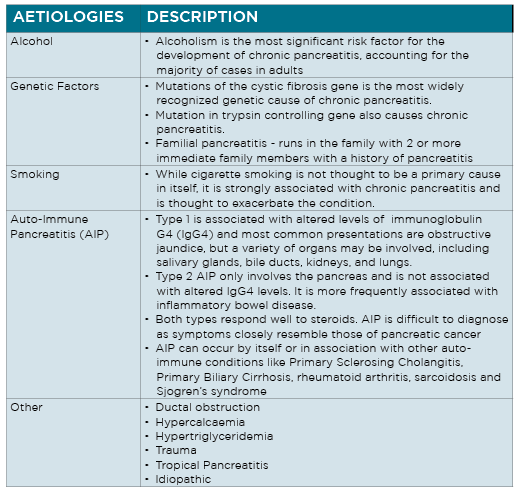

Determining the aetiology is a vital consideration in ensuring proper treatment and making appropriate lifestyle changes.

In Western countries, alcohol is the most common aetiological factor. One survey put alcohol as a factor in up to 95% of chronic pancreatitis cases in Australia.

Recurrent acute pancreatitis from any cause is another risk factor for the development of chronic pancreatitis. As per a recent study, the transition rate from the first episode of acute pancreatitis to a recurrent episode is approximately20% and, from recurrent acute pancreatitis to chronic pancreatitis, the rate is estimated to be about35%.

While quite a few cases of chronic pancreatitis are idiopathic, there are several established risk factors and aetiologies.

DIAGNOSIS

Chronic pancreatitis can be diagnosed at any age, however it most often develops in patients between the ages of 30 and 40, and is more common in men than women.

The clinical symptoms of chronic pancreatitis are varied and non-specific. Accurate diagnosis requires the recognition of a variety of symptoms and complications that constitute the disease. In some cases there are no obvious symptoms at all.

There is no accepted diagnostic gold standard for chronic pancreatitis. Of the array of diagnostic tests available,none provide diagnosis with 100% certainty, especially in the early stages of the disease.

Abdominal pain

The dominant presenting complaint of most patients is abdominal pain. It is usually epigastric, dull and constant in nature and almost always localised in the upper half of the abdomen, from where it can radiate directly through to the back, or laterally around to the left or right flank. Early in the course of the disease, the pain may be intermittent, but as the disease progresses, frequency and duration of the pain increases.

Exocrine insufficiency

Occasionally, chronic pancreatitis may present as unexplained weight-loss. The patient may also complain of chronic pain, diarrhoea and/or steatorrhoea (loose, greasy, foul-smelling stools that are difficult to flush). These symptoms of exocrine insufficiency (and related consequences, such as vitamin deficiency and osteoporosis) typically develop five to 10 years after initial onset of chronic pancreatitis.

Malabsorption of the fat soluble vitamins (A, D, E, K) and vitamin B12 may also occur, although clinically symptomatic vitamin deficiency is rare.

Endocrine insufficiency

Like exocrine insufficiency, endocrine insufficiency occurs in the later stages of the disease. Diabetes develops in chronic pancreatitis due to the destruction of islet cells. Diabetes associated with diseases of the pancreas is known as type 3c (pancreatogenic) diabetes. It has features of both type 1 and type 2 diabetes. It is characterised by swings between hyperglycaemia and hypoglycaemia.Diabetes is more likely to occur in patients with a family history of type 1 or type 2 diabetes.

Less common initial presentations

These include biliary obstruction with recurrent episodes of mild jaundice, cholangitis, or vague attacks of indigestion. Obstruction of the splenic vein may lead to left-sided portal hypertension, gastric varices and GI bleeding.

INVESTIGATIONS

The diagnosis of chronic pancreatitis is made based on a patient’s history, clinical presentation, and imaging and functional tests. There is no single test that can diagnose chronic pancreatitis, especially in the early stages.

In the later stages, morphological and functional changes in the pancreas are more obvious and it is easier to make an accurate diagnosis. However, by this stage, the disease is usually too advanced to halt that progression.

If chronic pancreatitis is suspected based on history and physical examination, a diagnostic workup should be initiated.

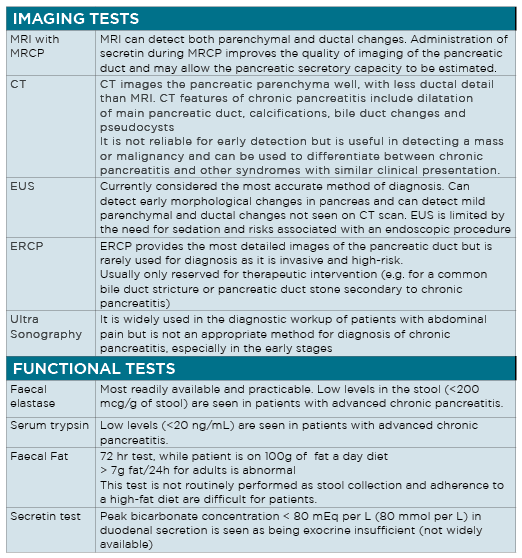

An array of laboratory tests and imaging procedures may be used in the evaluation of patients with suspected chronic pancreatitis and are summarised in table 2 on P30.

RISK OF MALIGNANCY

The complexity of the interaction between genetic and environmental factors that lead to disease progression from inflammation to malignancy are not yet fully understood.

It is widely accepted that chronic inflammation of the pancreas which characterises chronic pancreatitis also leads to metaplasia and neoplastic transformation. The exact mechanism of oncogenic mutations is not known. However, it is now believed malignancies occur at different rates in different aetiologies of the disease.

Known risk factors of pancreatic cancer include chronic pancreatitis, diabetes, hereditary pancreatitis, as well as smoking and alcohol consumption.

The life-time risk of developing pancreatic cancer is highest in patients with hereditary pancreatitis, at around 40%. NICE guidelines have recommended annual monitoring for pancreatic cancer in patients with hereditary pancreatitis.

Patients with pancreatic cancer may present with clinical symptoms similar to chronic pancreatitis, including weight loss, epigastric pain, and jaundice. It is necessary therefore that the diagnostic workup of chronic pancreatitis exclude possible malignancy.

The evidence suggests diabetes is both a risk factor as well as a symptom of pancreatic cancer.

Previous studies have shown a two-fold higher risk of developing pancreatic cancer in patients with longstanding diabetes.

And for people newly diagnosed with diabetes, a recent multi-ethnic cohort study, found the risk of pancreatic cancer was 2.3-fold higher in new-onset diabetes compared with long-standing diabetes. In this study, the majority of these patients had developed diabetes in the 36 months prior to the diagnosis of cancer. These findings supported the study hypotheses that new-onset diabetes is a manifestation of pancreatic cancer whereas long-standing diabetes is a risk factor.

MEDICAL MANAGEMENT

No curative treatment for chronic pancreatitis exists. Determining disease aetiology provides opportunities for focused and specific treatments. Management options for chronic pancreatitis include medical, endoscopic and surgical treatments as well as lifestyle modifications to slow disease progression and preserve pancreatic tissue.

GPs have an important role in treating chronic pain, endocrine/exocrine impairment, determining the need for referral,patient education and care-coordination between the hospital and home.

Treatment of pain

As well as being the most common presenting symptom of chronic pancreatitis, abdominal painis also the most difficult to manage. It is the most frequent reasonpatients seek medical care and causes the greatest deterioration in social function and quality of life.

Pain treatment begins with medical therapy. For most , pain is due to inflammatory irritation of parenchymal nerve endings.

Management, therefore, utilises a step-up pharmacological approach, starting with non-opioids (e.g. paracetamol, ibuprofen), progressing to mild opioids (e.g. codeine, tramadol) and, finally, strong opioids (e.g. morphine, oxycodone).

Patients should be counselled on the risk of opioid-dependency. Patients with previous addictive behaviours, including alcohol abuse or smoking, are most at risk of abuse or addiction.

For patients who do not respond to medical therapy, options include endoscopic therapy, neurolysis or surgery.

In a small proportion of patients, pain is due to some underlying structural cause, such as obstruction of the main pancreatic duct by calculi or strictures. Further diagnostic imaging may be indicated to investigate the exact cause.

Patients with ductal obstruction need to be referred to a specialist for consideration of a drainage and/or resection procedure. Distal pancreatic duct strictures may be amenable to endoscopic stenting.

On occasion, imaging may also reveal one or more pseudocysts. These alone are unlikely to be the cause of chronic pain, but if a pseudocyst is sufficiently large, the patient can be referred for consideration of an endoscopic drainage.

Treatment of pancreatic exocrine insufficiency

The gold standard treatment of pancreatic exocrine insifficiency is pancreatic enzyme replacement therapy (PERT) which helps reduce fat malabsorption and restore normal nutrition.

A number of commercially available digestive enzyme combinations are available. Most are enteric-coated, however they may need to be co-treated with acid suppression medication as gastric acid can reduce potency of medication.

The dosage of PERT should be titrated depending on factors such as symptoms, food eaten, and cooking methods. The patient should be educated regarding adjusting the dose and may need to be referred to a specialist dietician to better understand the dietary requirements.

There is no need to avoid dietary fat as low-moderate fat intake is acceptable. Very low fat, or fat-free, diets are not recommended. Before patients begin therapy, a baseline evaluation of nutritional status should be done. This should include weight and body mass index, as well as laboratory tests including FBC, biochemistry, INR, and levels of albumin and vitamin D.

As per NICE guidelines, all patients with chronic pancreatitis should be offered monitoring by clinical and biochemical assessment for pancreatic exocrine insufficiency and malabsorption every 12 months.

Treatment of pancreatic diabetes

Patients with chronic pancreatitis have a greatly increased risk of developing diabetes, with a lifetime risk as high as 80%. The risk increases with duration of pancreatitis and presence of calcific pancreatitis. Once diagnosed, patients should be referred to a specialist clinic for initial stabilisation and education. Management is complicated by poor dietary intake, alcohol consumption, malabsorption, and undernutrition. When properly treated, pancreatic diabetes may be no more difficult to manage than other types of diabetes. For patients with chronic pancreatitis who have not yet been diagnosed with diabetes, endocrine function should be assessed every six months (glycated haemoglobin, HbA1c), and where results are equivocal, consider oral glucose tolerance testing.

LIFESTYLE MODIFICATIONS

Nutrition and bone health

Patients with chronic pancreatitis are at high risk of malnutrition and should be educated about healthy lifestyle choices. A specialist dietician should be involved for a structured nutritional assessment. Due to the increased risks of osteoporosis, osteopenia, and low-trauma fractures, patients need to be counselled regarding adequate calcium and vitamin D supplementation.

Periodic assessments of bone density and vitamin D is also recommended. Patients with osteopenia should undergo bone density scanning (DEXA) and repeat at two years. Patients with osteoporosis require appropriate medication and screening for associated diseases.

Alcohol abstinence, smoking cessation and diet

In cases where aetiology of chronic pancreatitis is alcohol, then full alcohol abstinence is a priority in disease management.

Even if there is no history of alcohol abuse, full abstinence is important, as alcohol consumption and smoking increase the risk of recurrent attacks of pancreatitis and disease progression. In a large Cochrane meta-analysis, brief interventions in primary care have been shown to reduce alcohol consumption. All patients should be counselled regarding complete alcohol avoidance and smoking cessation. This can delay disease progression as well as reducing the severity and frequency of the pain, especially in the early stages. Patients who continue to drink and/or smoke should be referred for addiction support/counselling. Even if complete abstinence is not achieved, reductions in alcohol consumption are likely to be useful.

A diet low in fat and high in protein and carbohydrates is recommended, especially in patients with steatorrhoea. The degree of fat restriction depends on the severity of fat malabsorption. Generally, an intake of up to 75g/day is sufficient. Malabsorption of the fat soluble vitamins (A, D, E, and K) and vitamin B12 may also occur. Supplementation of these vitamins is recommended. Specific dietary recommendations include a daily diet of 2000 to 3000 calories, consisting of 1.5-2g/kg of protein, 5-6g/kg of carbohydrates, and 20-25% of total calories consumed as fat (about 50-75g) per day.

Patient support and education

Chronic pancreatitis causes significant reductions in quality of life, and is associated with high rates of disability and depression. Educating patients about the disease as well as providing support and counselling can help individuals better cope with their diminished health. Counselling can also help patients make positive lifestyle changes, which can slow disease progression, especially in the early stages.

Dr Farzan Bahin is a gastroenterologist and hepatologist with an interest in advanced endoscopy. He is visiting medical officer at Blacktown and Mt Druitt Hospitals in Sydney.

Madiha Cheema is an advanced trainee in gastroenterology and hepatology at Blacktown Hospital in Sydney

References

- Hirota M, Shimosegawa T, Masamune A, et al. The sixth nationwide epidemiological survey of chronic pancreatitis in Japan. Pancreatology. 2012;12:79–84.

- Yadav D, Timmons L, Benson JT, et al. Incidence, prevalence, and survival of chronic pancreatitis: a population-based study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2011;106:2192–9.

- Duggan SN, Ní Chonchubhair HM, et al. Chronic pancreatitis: A diagnostic dilemma. World J Gastroenterol. 2016;22(7):2304–2313.

- Steven D Freedman, David C Whitcombhilpa Grover, et al. Clinical manifestations and diagnosis of chronic pancreatitis in adults. www.uptodate.com

- Duggan, Sinead N et al. “Chronic pancreatitis: A diagnostic dilemma.” World journal of gastroenterology vol. 22,7 (2016): 2304-13.

- Barry K. Chronic Pancreatitis: Diagnosis and Treatment. Am Fam Physician. 2018;97:385–393.

- Ni Chonchubhair H, O’Shea B, et al. The Management of Chronic Pancreatitis in Primary Care. University of Dublin Quality in Practice Committee. 2017

- Nair RJ, Lawler L, et al. Chronic Pancreatitis. Am Fam Physician. 2007 Dec 1;76(11):1679-88.

- Huffman, J., Obideen, K. and Wehbi, M. (2019). Chronic Pancreatitis. [online] Emedicine.medscape.com. Available at: https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/181554-overview [Accessed 6 Aug. 2019].

- Forsmark CE, Management of Chronic Pancreatitis. Gastroenterology 2013;144:1282–1291

- Freedman, S. (2019). Clinical manifestations and diagnosis of chronic pancreatitis in adults. [online]

- Garg P.K., Tandon R.K. (2004) Survey on chronic pancreatitis in the Asia-Pacific region. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol., 19, 998–1004

- Yadav D, O’Connell M, et al. Natural history following the first attack of acute pancreatitis. Am J Gastroenterol 2012;107:1096–103.

- Engjom, Trond et al. “Diagnostic Accuracy of a Short Endoscopic Secretin Test in Patients With Cystic Fibrosis.” Pancreas vol. 44,8 (2015): 1266-72. doi:10.1097/MPA.0000000000000425

- Khan, A. (2019). Chronic Pancreatitis Imaging. [online] Emedicine.medscape.com. Available at: https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/371772-overview

- Kaner EF, Beyer F, et al. Effectiveness of brief alcohol interventions in primary care populations. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007(2):CD004148.