The most frequent sign of thyroid eye disease is eyelid retraction.

Thyroid eye disease is an autoimmune process which affects the tissues of the orbit behind the eye.

This can cause disfiguring protrusion (proptosis) of one or both eyes, double vision (diplopia) and can threaten sight via pressure on the optic nerve, or by exposure of the cornea.

Thyroid eye disease is the commonest extrathyroidal manifestation of Graves’ hyperthyroidism, but can also affect euthyroid patients and hypothyroid patients (e.g. from Hashimoto’s thyroiditis).(1)

EPIDEMIOLOGY

Graves’ disease affects approximately 1% to 2% of adults with a mean age of diagnosis of 45, and a five times greater prevalence among females. (2)

Approximately 40% of patients with Graves’ disease will be affected by thyroid eye disease during their lifetime, with a mean onset around 18 months after diagnosis of Graves’ disease. (3)

Smoking is the strongest modifiable risk factor for developing thyroid eye disease which is five times more common in smokers than non-smokers, and disease severity is greater among current smokers. (4)

PATHOLOGY

In essence, thyroid eye disease involves accumulation of tissue and fluid which causes pressure on the orbital contents.

Thyroid eye disease is described as having an initial active phase, followed by an inactive phase. The active phase is characterised by inflammation and infiltration of orbital tissues by immune cells. Glycosaminoglycans are deposited, causing oedema due to the hydrophilic effect of these molecules. The extraocular muscles are the most frequently affected tissues, resulting in swelling and fibrosis.

Adipogenesis also occurs in the orbit.(5) This process gradually stabilises as the process enters the inactive phase.

PRESENTATION

The most frequent sign of thyroid eye disease is eyelid retraction. This condition is present in more than 90% of patients.

Patients may also have visible oedema and erythema of the periorbital tissues.

Proptosis and lid-lag (where movement of the upper eyelid lags behind vertical downward eyeball movement) are also common. Dysfunction of the extraocular muscles can lead to diplopia.

Incomplete eyelid closure (lagophthalmos) may develop and patients may complain of exposure symptoms, such as foreign body sensation, grittiness, photophobia, or lacrimation. These are secondary to the wide palpebral aperture and poor blinking, leading to increased tear evaporation.

Swelling of muscles at the apex of the orbit can cause pressure on the optic nerve leading optic neuropathy. This is only seen in severe disease (5% of patients).(5)

INVESTIGATIONS

There is no single clinical finding or laboratory test that is diagnostic of thyroid eye disease. Assessment of the thyroid function and antibodies are more relevant to treatment of the associated thyroid condition.

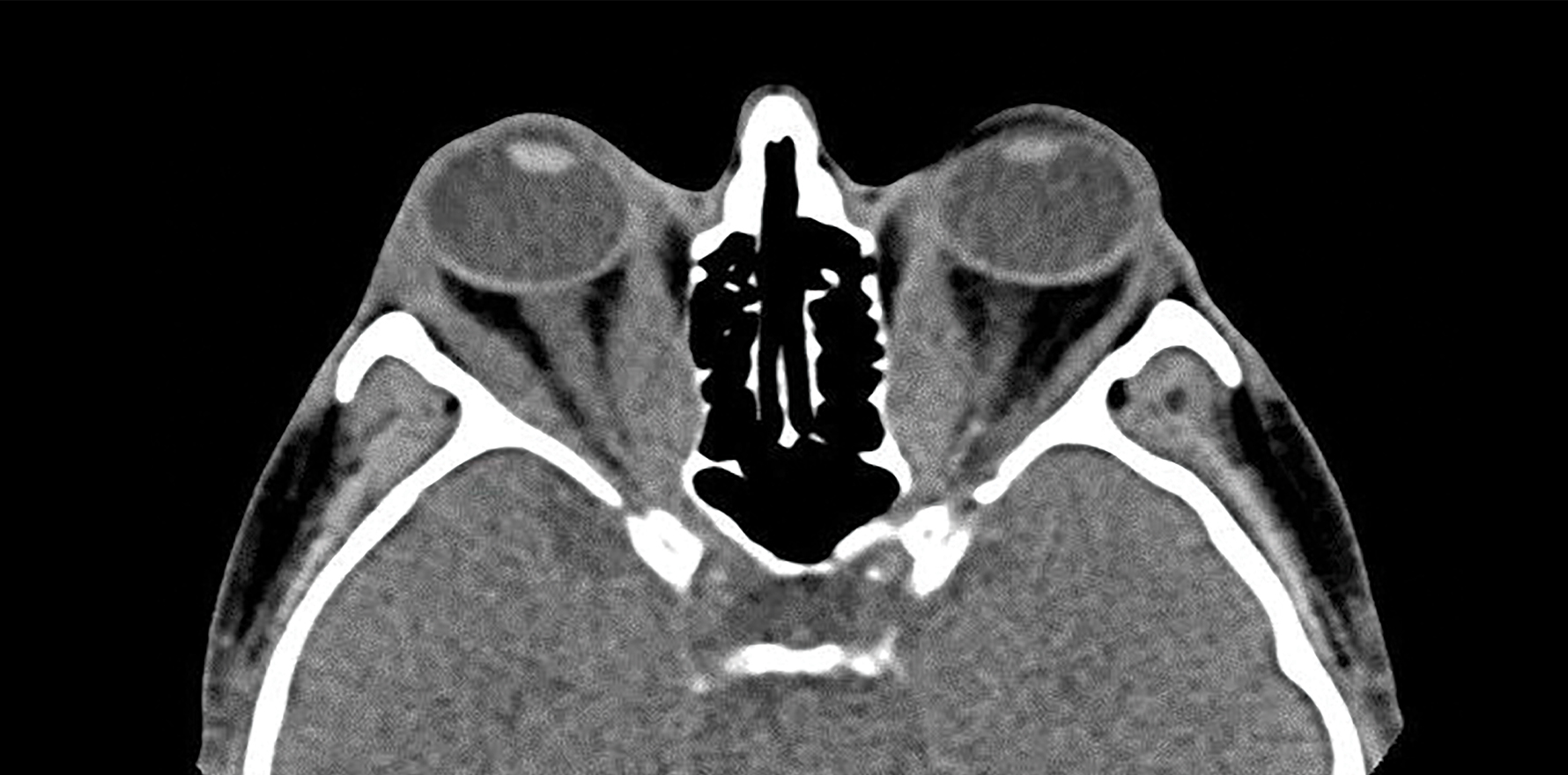

CT is the most common imaging modality for evaluating thyroid eye disease. Findings may include muscle belly enlargement, an increase in orbital fat volume, and crowding of the optic nerve at the orbital apex. Additionally, it allows the relevant anatomy to be clearly defined prior to surgical or radiotherapeutic intervention

TREATMENT

Treatments for thyroid eye disease aim to relieve symptoms, preserve and optimise vision, reduce inflammation, correct strabismus and improve cosmetic appearance. Optimisation of the thyroid status is important, but does not alter the underlying pathology of thyroid eye disease. (6)

Generally, patients should be advised regarding the risks ofsmoking and the benefits of cessation.

Symptomatic relief may be achieved by supportive measures such as head elevation in sleep to reduce periorbital oedema, ocular lubrication, and sunglasses to reduce photophobia. More specific treatments depend on the activity and severity of the disease process.

In the active phase, the inflammatory process may be targeted by steroids and immunomodulatory agents such as cyclosporine or azathioprine. Radiotherapy has also been used to reduce inflammation.

Recently, a monoclonal antibody to the insulin-like growth factor I receptor (IGF-IR), called teprotumumab, was shown to be effective in treating active thyroid eye disease, and has been granted FDA approval in the US. (7)

The inactive phase is characterised by stable alterations in the orbital tissues such as fibrosis and fat deposition. Consequently, treatments for this phase of the condition are primarily surgical and are generally considered after the patient has been stable for around six months, except where there is imminent threat to sight from compressive optic neuropathy, or exposure of the cornea.

An important sequence of interventions should be followed whereby decompression of the orbit is performed prior to extraocular muscle surgery, which in turn precedes eyelid surgery. This is because the former procedures will have a direct effect on the subsequent issues. (8)

Orbital decompression involves removing the bony orbital wall, to make room for the enlarged extraocular muscles. Orbital fat may also be removed. This can be achieved endoscopically via the nose in many cases, meaning that there is no apparent scar and facilitating a rapid recovery.

Strabismus surgery typically involves a recession procedure whereby an extraocular muscle is detached from the eye and re-attached further back, to reduce its relative strength. Adjustable sutures may be used which can allow fine-tuning of the procedure during the early post-operative course.

Correction of eyelid retraction is the final stage of surgical intervention. This can be achieved by lengthening the muscles of the eyelid and thus reducing the amount of sclera on show.

WHEN TO REFER

Referral to an ophthalmologist is encouraged for patients with ocular or cosmetic symptoms.

Urgent referral is necessary in the presence of vision-threatening disease.

Due to the complexity of management of these patients, and the tendency for care to be delayed and fragmented, a multidisciplinary clinic has been established at Royal Prince Alfred Hospital in conjunction with the University of Sydney.

This monthly bulk-billing clinic is the first of its kind in Australia, and involves specialists from ophthalmology, including orbital surgery, strabismus surgery, oculoplastics and ocular immunology, as well as endocrinology, radiology, and radiation oncology.

At the time of writing this article we are gathering data on the outcomes of the clinic for publication. We expect to show good outcomes for these patients who suffer from a condition that can have a profound effect on quality of life.

Associate Professor Raf Ghabrial is a senior surgeon at Royal prince Alfred hospital and Sydney Eye Hospital and is the first academic orbital surgeon appointed to the University of Sydney

Dr Timothy Holmes is an ophthalmology registrar and conjoint lecturer at University of NSW. He has an interest in oculoplastics, medical education and public health

References:

1. Bartalena L, Baldeschi L, Dickinson A, Eckstein A, Kendall-Taylor P, Marcocci C, et al. Consensus statement of the European Group on Graves’ orbitopathy (EUGOGO) on management of GO. European Journal of Endocrinology. 2008;158(3):273-85.

2. Wemeau JL, Klein M, Sadoul JL, Briet C, Velayoudom-Cephise FL. Graves’ disease: Introduction, epidemiology, endogenous and environmental pathogenic factors. Ann Endocrinol (Paris). 2018;79(6):599-607.

3. Mohyi M, Smith TJ. IGF1 receptor and thyroid-associated ophthalmopathy. J Mol Endocrinol. 2018;61(1):T29-T43.

4. Cawood TJ, Moriarty P, O’Farrelly C, O’Shea D. Smoking and thyroid-associated ophthalmopathy: A novel explanation of the biological link. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007;92(1):59-64.

5. Maheshwari R, Weis E. Thyroid associated orbitopathy. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2012;60(2):87-93.

6. Weiler DL. Thyroid eye disease: a review. Clinical & Experimental Optometry.100(1):20-5.

7. Douglas RS, Kahaly GJ, Patel A, Sile S, Thompson EHZ, Perdok R, et al. Teprotumumab for the Treatment of Active Thyroid Eye Disease. New England Journal of Medicine. 2020;382(4):341-52.

8. Ghabrial R. Thyroid Eye Disease. Mivision: the Ophthalmic Journal. 2010.