The condition is grossly underdiagnosed, with only half of patients realising they have it and even fewer receiving a diagnosis.

Migraine is a highly prevalent and complex neurological disorder underpinned by dysfunction of sensory processing and presenting with recurrent episodes of headache and neurological symptoms.

Yet despite its high prevalence, migraine is grossly underdiagnosed in primary care settings1. Only half of the patients identified as having migraine in a population-based survey knew they had migraine and less than half had received a formal diagnosis of migraine. Accurate diagnosis allows the patient opportunity to benefit from specific treatment.

Uncertainty regarding sinister aetiologies provokes diagnostic anxiety, which may be overcome by clinical reasoning and effective diagnostic algorithms. Identifying the minority of secondary headache syndromes without subjecting the great majority of patients to unnecessary investigations is the goal. We aim in this article to provide some practical advice that will assist the accurate diagnosis of migraine.

Epidemiology and disease burden of migraine

An interview-based study conducted in Australia of more than 3000 adults greater aged 50 and over identified an overall 17% prevalence of migraine, with 22% of women affected2.

Incorrect diagnoses represent missed opportunities for treatment, contributing to the burden of migraine as well as its conversion to chronic migraine. Chronic migraine is defined as >15 headache days per month for more than three months and has a 2% prevalence3, with 2.5% of episodic migraineurs converting to a chronic pattern annually4.

The conversion risk doubles in those using narcotic analgesics4.

Unsurprisingly, the Global Burden of Disease 2019 study ranks headache disorders as the second-leading cause of years lived with disability worldwide5. Much of the burden is attributed to loss of function and absenteeism.

Important steps to making a quick and correct diagnosis of headaches

Step 1: Characterise the patient’s headache and use the SNOOP4 mnemonic

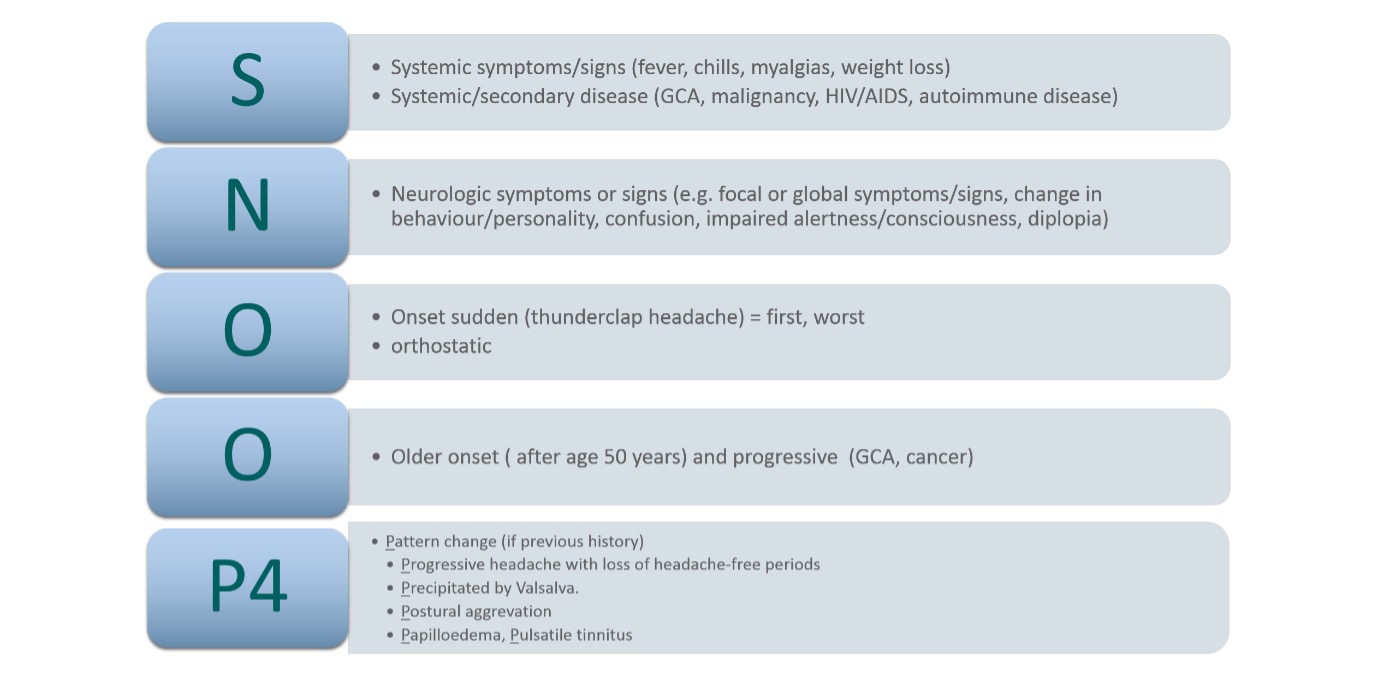

Given there are no useful biomarkers to assist primary headache diagnosis, a correct headache diagnosis depends on fully characterising the patient’s headache (table 1) and ruling out secondary causes via systematic specific questioning using the “SNOOP4” mnemonic coined by Dodick et al. SNOOP4 methodically identifies red flag features for secondary headache disorders6 (see figure 1).

| Headache features | Examples or specific comments |

| Triggers | Relationship to menstruation, alcohol, sleep deprivation, glare, loud noise, odours, exertion, dietary, physical (e.g. head trauma, minor concussion), medications (e.g. nitrates) |

| Prodrome | Yawning, appetite change or food cravings, irritability, depressive symptoms, fatigue, thirst |

| Aura | Typical auras (i.e. visual, sensory, language/speech) as well as retinal, brainstem, hemiplegic auras |

| Temporal course | New onset/sudden/subacute (hours to days)/chronic (months to years) |

| Lateralisation and location | Unilateral versus bilateral? Frontal, retroorbital, temporal, occipital? |

| Character | Pulsating, throbbing, pounding |

| Intensity | Visual analogue scale (0-10) or mild/moderate/severe |

| Associated symptoms | Sensory symptoms (photophobia, phonophobia, osmophobia)Gastrointestinal symptoms (nausea, vomiting)Cutaneous allodynia |

| Duration of each attack | Seconds/minutes/hours/days |

| Frequency of attacks | Attack frequency per month (or per day if multiple brief attacks) |

To maximise the potential of SNOOP4, a working knowledge of common secondary headaches is crucial to guiding urgent investigations. Table 2 lists the most important secondary headaches, their typical manifestations, common aetiologies and useful investigations.

| Category of secondary headache syndrome | Clinical manifestations | Examples of possible aetiologies | Useful investigations |

| Thunderclap headache | Sudden, new-onset headache with peak intensity within seconds | – Intracerebral haemorrhage – Subarachnoid haemorrhage or its sentinel headache – Pituitary apoplexy – Haemorrhage into mass lesion – Arterial dissection – RCVS VST – Spontaneous intracranial hypotension – Intracranial infection | CT/CTA scanLP for xanthochromia MRI/MRA with fat-saturation protocol |

| Headache with new focal neurological signs, confusion or drowsiness | Lateralising deficit (eg hemiparesis) Seizures Fluctuating level of consciousness | – Stroke especially posterior circulation stroke – Meningitis / encephalitis – VST | CT MRI CT or MR venography LP |

| Headaches with onset after head and neck trauma | History of significant head or neck injury | – Subdural or epidural haemorrhage – Arterial dissection – Post-carotid endarterectomy hyperperfusion headache | CTA MRI/MRA with fat-saturation protocol |

| Late onset headaches (i.e. in the older than 50 year old group) | Late onset headache especially in patient previously not reporting migraines | – Vasculitis (eg giant cell arteritis) – Mass lesion – Stroke – Metastases – Carcinomatous leptomeningeal involvement | ESR,CRP MRI or CT with contrast PET |

| Headache in the immunosuppressed patient | History of HIV, cancer, immunosuppressants, chemotherapy or corticosteroid use | – Meningitis – Abscess – metastases | MRI LP |

| Headache that is gradually worsening in frequency | Especially if worsening parallel with causative disorderFever may suggest inflammatory cause | – space occupying lesion – subdural haemorrhage – analgesic overuse and rebound – systemic infection – meningitis / encephalitis – vasculitis | CT, MRI, ESR, CRP |

| Headache with papilloedema | Ophthalmology review | – mass lesion – IIH – VST | MRI/MRV including orbits LP including OP in lateral decubitus position Fundoscopy Visual field testing OCT |

| Headache worse with positional changes | Worse when standing (low pressure) Worse when coughing (high pressure) | – Spontaneous intracranial hypotension – Space occupying lesion – Posterior fossa lesion – Chiari malformation | MRI with and without contrast Empiric CSF blood patch for SIH |

Abbreviations: HIV (human immunodeficiency virus), CT (computed tomography), MRI (magnetic resonance imaging), RCVS (reversible cerebral vasoconstriction syndrome), LP (lumbar puncture), OP (opening pressure), PET (positron emission topography), IIH (idiopathic intracranial hypertension), VST venous sinus thrombosis, OCT (optic coherence tomography), SIH (spontaneous intracranial hypotension)

Important messages regarding the work-up of secondary headaches are:

- some secondary headaches have pain ipsilateral to the secondary cause;

- always work up new-onset headaches in the elderly;

- comorbidities are important; and

- magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is generally superior to computed tomography (CT) in ruling in secondary headaches.

Precision is critical regarding what constitutes a thunderclap, by asking specifically how quickly the headache reached its peak intensity from baseline of no pain. If unsure, ask again with multiple-choice cues: “Within a few seconds, minutes or hours?”. A thunderclap headache should peak within seconds. Thunderclap headache is defined as a severe headache that reaches peak intensity almost instantaneously, typically within seconds from baseline, and often described as the patient’s worst headache in their life.

Across ED settings, the probability of secondary headache disorders ranges from 21% to 46%7-9 in patients presenting with severe or thunderclap headache, while subarachnoid haemorrhage (SAH) is the aetiology in 10-30% of such cases.

Consider a patient who has a new onset headache occurring at an older age. This scenario should prompt consideration of giant cell arteritis, especially if jaw claudication or elevated inflammatory markers are present.

Subacute presentations may suggest infectious, inflammatory or neoplastic causes. Then it follows that a static-severity, episodic, disabling headache occurring for more than six months is likely to be migraine until proven otherwise10. More specifically, the likelihood of migraine (or probable migraine) in this setting is over 90%10. More comprehensive reviews on secondary headaches, including thunderclap headache, exist elsewhere11.

Step 2: Enquire about triggers, prodromal symptoms, aura and headache characteristics

Migraine can be triggered by glare, loud noise, odours, exertion, dehydration, certain foods, drugs (e.g. nitrates), alcohol, sleep disturbance, physical trauma, stress and hormonal influences.

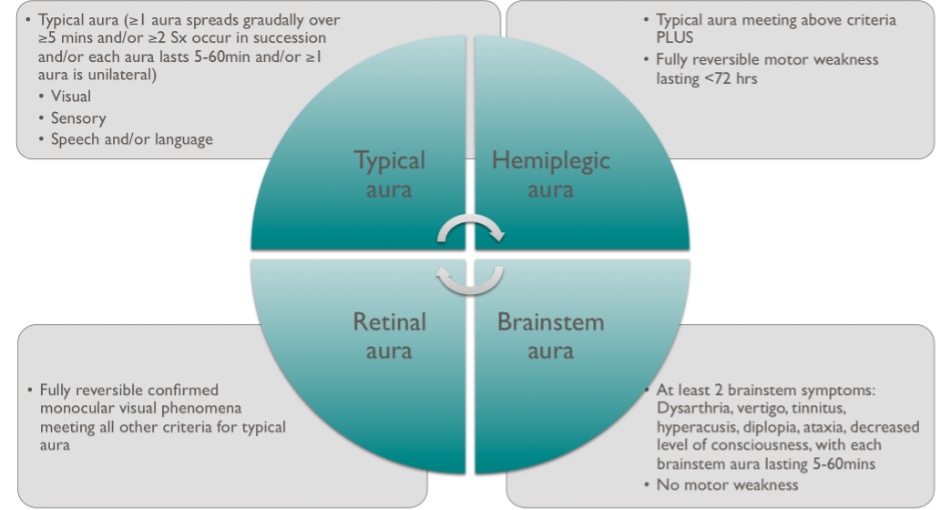

Prodromal symptoms can occur early in a migraine including irritability, excessive yawning, thirst, food cravings and fatigue12. Aura symptoms (figure 2) can occur before, with or during headache but occur in only around 20-30% of migraineurs13, and not necessarily with every attack. Patients can have more than one aura symptom during each attack and these can occur in succession.

Aura in the absence of headache may cause patients or doctors to be concerned about sinister pathologies such as stroke and other neurological disorders. Fortunately, the typical pattern of visual aura with evolution over 20 to 30 minutes and a mixture of positive and negative phenomena is so characteristic that a confident clinical diagnosis can usually be made.

The clinical hallmark of a migraine attack is head pain. The headache is bilateral in at least 40% of adults, with a median reported intensity of eight out of 1014 with more than 75% of patients reporting severe pain during attacks15.

Migraine can be associated with various sensory phenomena (such as photophobia, phonophobia, osmophobia, cutaneous allodynia) and gastrointestinal disturbance, most commonly nausea and vomiting. These can be worse than the headache itself. Only around half of patients would describe their headaches as pulsating13.

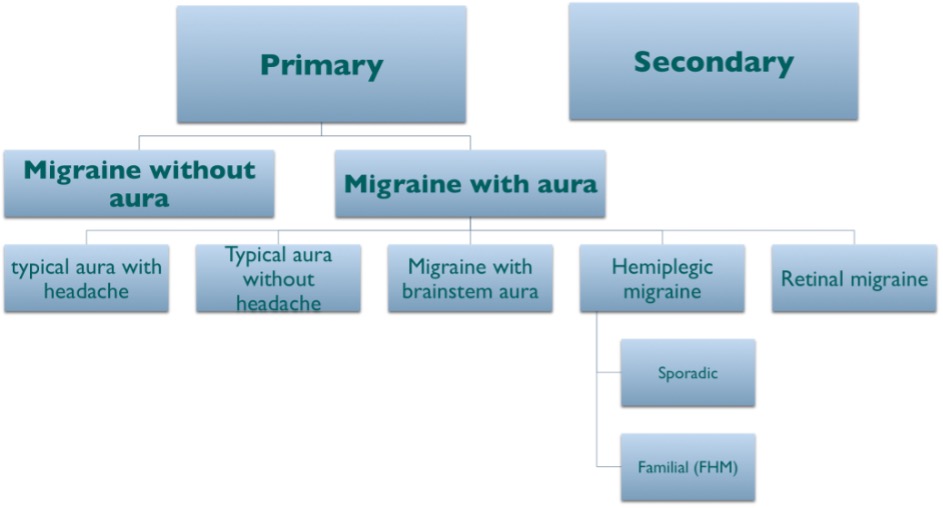

The danger, in patients who do not have aura, is that the diagnosis of migraine may not be easily recognised without this well-known feature. Once the important clinical features of the migraine experience are gathered, the clinician should see which International Classification of Headache Disorder version 3 (ICHD-3) criteria16 apply to diagnose the patient’s headache disorder. Figure 4 provides a broad classification scheme to help illustrate this concept.

| 1) when you have a headache, does light bother you? (Photophobia) 2) in the last 3 months, has a headache interfered with your activities with your activities on at least one day? (Impact to ADLs) 3) when you have a headache, do you feel nauseated? (Nausea) Sensitivity = 0.81, Specificity = 0.75 for diagnosis of migraine if answer yes to 2 out of 3 questions above |

All patients presenting with headache for the first time require a systematic yet focused physical examination, including fundoscopy, oculomotor, cranial nerve, gait and motor examination. Vital observations including blood pressure, heart rate, temperature and body mass index should be routine.

Examination aims to exclude findings suggestive of a secondary cause, such as focal neurological deficits and papilloedema. Such signs have reasonable positive predictive value (PPV). Ramirez-Lassepas and colleagues17 found secondary headache disorders in 44% of ED patients with a complaint of headache with an abnormal neurological examination as compared with only 2% of those with a normal neurological examination.

The positive likelihood ratio for secondary headache disorders was 16.2 for an abnormal neurological exam. Given that most patients with chronic recurrent stereotypical headaches presenting in the clinic setting will have migraine, it also follows that most will have a normal neurological examination.

Step 3: Differentiating migraine with aura from other vascular conditions

It is often not easy to tell if the patient who is experiencing acute transient neurological symptoms has migraine versus a transient ischaemic attack (TIA) or stroke.

There have been various clinical pearls (table 3) provided by distinguished neurologists over the years18 to help clinicians distinguish migraine with aura from acute vascular events.

| Migraine with aura | Transient ischaemic attack | |

| Visual symptoms | Positive phenomenon: Scintillating scotomasCan be mobile visual symptoms | Negative visual phenomenon:Loss of vision |

| Temporal course | Gradual onset/evolution over 15-20minsSequential progression | Onset is sudden, simultaneous and maximum at onset |

| Duration | Average duration 20-30 minutes up to an hour | Brief, seconds to minutes (usually less than 15 minutes) |

| Recurrence | Recurrences may be similar in natureFlurry of attacks can occur usually mid-life | Typically should not be stereotyped recurrence unless crescendo TIA |

| Headache | Headache may follow aura | Headache uncommon unless posterior circulation TIA |

Abbrievations: TIA = transient ischaemic attack

Step 4: Brief screening questionnaires can assist quick diagnosis of migraine in primary care

There are several validated screening questionnaires that can be applied in clinical settings to make a quick and acceptably accurate diagnosis of migraine.

ID MigraineTM (figure 4), first described by Lipton and colleagues19, is a three-symptom, self-administered migraine screener with established validity and reliability in diagnosing migraine in a recent systematic review20. The presence of two out of three symptoms has a sensitivity of 81%, specificity of 75% and PPV of 93%.

An illustrative case study:

A 32-year-old man presents with intermittent neurological symptoms. These include episodes of visual and sensory disturbance. They have occurred about six times a year for the past three years.

Teaching point: The key to clarifying the nature of the disturbance is the detail of how it evolves. TIAs tend to develop abruptly while focal seizures evolve over a minute or two. Migraine aura evolves over 20-30 minutes usually.

The patient describes that his episodes start with an ill-defined blurring in the centre of vision. Within five minutes, there is a clearly defined area of central visual field loss. This then gradually spreads towards the edge of the peripheral field, usually to the left but occasionally to the right. The advancing edge of the visual disturbance has a shimmering jagged quality. After about 20 minutes, the problem is confined to the peripheral visual field and central vision improves. At this stage there is sometimes some tingling of the left hand for a few minutes. Within 35 minutes of onset the symptoms have all resolved. There is then often a bifrontal headache, usually mild to moderate in degree but sometimes severe with nausea and vomiting.

Teaching point: The history is typical of migraine with aura. There is rarely an underlying structural cause. Neurological examination should be done to exclude residual deficits (e.g., a persisting visual field defect). Most patients with typical aura will have normal imaging, but any atypical features would mandate imaging, preferably MRI.

Differential diagnosis of chronic headache disorders; for example, tension-type headache (TTH)

The most common differential of migraine is tension type headache (TTH).

The ICHD-3 classification allows TTH having limited features of migraine – specifically one feature of photophobia or phonophobia are allowed. The criteria do not allow nausea or aggravation by physical activity, either of which should lead to a diagnosis of migraine instead16. Increasing migrainous features make a migraine diagnosis more likely21.

Similarly, there are overlapping features of TTH being recognised in chronic migraine16. Compared with migraine, the headache of TTH is more often bilateral, pressing or tightening rather than pulsating and of mild or moderate intensity16. This character of headache is allowed also in the definition of chronic migraine, although eight of the headache days should still have some migrainous features. In the case of mixed features of TTH and migraine, chronic migraine is the overriding diagnosis.

Despite the overlapping features, TTH is considered to have a different pathophysiology. Increased tenderness in the pericranial myofascial tissues, referred pain from trigger points and decreased pain thresholds occur in TTH22. For example, botulinum toxin does not alleviate TTH, despite these theories of muscle spasm, instead working through the neural pathways in chronic migraine. The complex biology of TTH is likely to be multifactorial and warrants further research23.

If there is analgesic medication overuse headache (MOH) present, then this is an additional diagnosis to the primary diagnosis of chronic migraine. Headache days are often under-reported by patients to focus on the more severe headaches, so specifically ascertaining the number of completely headache-free days is helpful.

A headache diary can demonstrate the frequency, triggers and treatment response, for the patient and physician.

Hemicrania continua, which is characterised as a constant hemicranial headache with ipsilateral autonomic signs, is an exquisitely indomethacin-responsive chronic headache disorder, albeit rare.

A constant headache from an exact recalled moment may indicate the rare disorder of new daily persistent headache (NDPH), which can be refractory, and a referral to a headache specialist may be required. In the end, the most commonly encountered chronic headache in clinical practice due to the combined prevalence and debility is chronic migraine, but on the bright side, it represents a highly treatable disorder.

Investigation and its role (or lack of role) in the diagnosis of migraine

Consideration of imaging in presumed primary headache can be a vexed issue. Cerebral imaging with CT or MRI has low yield. Major abnormalities are found in less than 2% of all patients referred for primary headache24-26 and occur in less than 0.2% of patients with a normal neurological examination27.

Abnormalities found are often not significant or are unrelated to the primary presentation24,28. Incidental findings occur in up to 20% of healthy adult brain MRIs29. Typically, imaging should be reserved for those with focal neurological deficit, a new or clear change in headache pattern or uncertainty around the possibility of a secondary cause. Imaging is not needed if primary headache is diagnosed and imaging has been previously completed, even if many years ago. Despite this, imaging is often requested outside published guidelines in an attempt to provide reassurance25, but subsequent incidental findings can ironically cause more angst than reassurance. If neuroimaging is performed, then MRI is preferred to CT because of the lack of radiation exposure and the greater resolution and sensitivity for identifying abnormalities27.

Conclusion

Migraine is common and tends to be underdiagnosed in primary care. This is unfortunate as there are many current and emerging highly effective treatments that patients will not have the opportunity to use if their condition is not diagnosed.

General practitioners are naturally and appropriately concerned about missing dangerous rare causes for headache but there are algorithms that can help with this. However, failure to diagnose migraine when it is present is much more common than incorrectly diagnosing it when it is not.

Patients have often been reluctant to present for medical attention for migraine, assuming that it is simply their lot in life and that medical treatments are no more use than they were a generation ago. We need to engage with them with a positive attitude. We are understanding migraine better year by year. We now have many effective treatments and more will be available in the near future.

Authors: Benjamin Kwok-Tung Tsang MBBS, FRACP, BPharm; Craig Costello MBBS, FRACP; Bronwyn Jenkins MBBS, FRACP; Richard Stark MBBS, FRACP.

Dr Ben Tsang trained as a neurologist at the Austin Hospital, Alfred Hospital, and the Royal Free Hospital in London followed by a post-fellowship year at the Neuro-Otology Department of the National Hospital of Neurology and Neurosurgery in London (“Queen Square”). His interest areas include neuro-otology, neuro-ophthalmology and headache disorders. He currently has a hospital appointment at Sunshine Coast University Hospital.

Competing interests and funding: none.

References

- Sadovsky R, Dodick DW. Identifying migraine in primary care settings. Am J Med. 2005;118 Suppl 1:11S-7S.

- Mitchell P, Wang JJ, Currie J, Cumming RG, Smith W. Prevalence and vascular associations with migraine in older Australians. Aust N Z J Med. 1998;28(5):627-32.

- Natoli JL, Manack A, Dean B, Butler Q, Turkel CC, Stovner L, et al. Global prevalence of chronic migraine: a systematic review. Cephalalgia. 2010;30(5):599-609.

- Bigal ME, Serrano D, Buse D, Scher A, Stewart WF, Lipton RB. Acute migraine medications and evolution from episodic to chronic migraine: a longitudinal population-based study. Headache. 2008;48(8):1157-68.

- Steiner TJ, Stovner LJ, Jensen R, Uluduz D, Katsarava Z, Lifting The Burden: the Global Campaign against H. Migraine remains second among the world’s causes of disability, and first among young women: findings from GBD2019. J Headache Pain. 2020;21(1):137.

- Dodick DW. Pearls: headache. Semin Neurol. 2010;30(1):74-81.

- Bo SH, Davidsen EM, Gulbrandsen P, Dietrichs E. Acute headache: a prospective diagnostic work-up of patients admitted to a general hospital. Eur J Neurol. 2008;15(12):1293-9.

- Landtblom AM, Fridriksson S, Boivie J, Hillman J, Johansson G, Johansson I. Sudden onset headache: a prospective study of features, incidence and causes. Cephalalgia. 2002;22(5):354-60.

- Linn FH, Wijdicks EF, van der Graaf Y, Weerdesteyn-van Vliet FA, Bartelds AI, van Gijn J. Prospective study of sentinel headache in aneurysmal subarachnoid haemorrhage. Lancet. 1994;344(8922):590-3.

- Tepper SJ, Tepper D. The Cleveland Clinic Manual of Headache Therapy. Second Edition ed. New York: Springer International Publishing; 2014.

- Chou DE. Secondary Headache Syndromes. Continuum (Minneap Minn). 2018;24(4, Headache):1179-91.

- Charles A. Advances in the basic and clinical science of migraine. Ann Neurol. 2009;65(5):491-8.

- Wober-Bingol C, Wober C, Karwautz A, Auterith A, Serim M, Zebenholzer K, et al. Clinical features of migraine: a cross-sectional study in patients aged three to sixty-nine. Cephalalgia. 2004;24(1):12-7.

- Lipton RB, Hamelsky SW, Kolodner KB, Steiner TJ, Stewart WF. Migraine, quality of life, and depression: a population-based case-control study. Neurology. 2000;55(5):629-35.

- Lipton RB, Stewart WF, Diamond S, Diamond ML, Reed M. Prevalence and burden of migraine in the United States: data from the American Migraine Study II. Headache. 2001;41(7):646-57.

- Headache Classification Committee of the International Headache Society (IHS) The International Classification of Headache Disorders, 3rd edition. Cephalalgia. 2018;38(1):1-211.

- Ramirez-Lassepas M, Espinosa CE, Cicero JJ, Johnston KL, Cipolle RJ, Barber DL. Predictors of intracranial pathologic findings in patients who seek emergency care because of headache. Arch Neurol. 1997;54(12):1506-9.

- Fisher CM. Late-life migraine accompaniments–further experience. Stroke. 1986;17(5):1033-42.

- Lipton RB, Dodick D, Sadovsky R, Kolodner K, Endicott J, Hettiarachchi J, et al. A self-administered screener for migraine in primary care: The ID Migraine validation study. Neurology. 2003;61(3):375-82.

- Cousins G, Hijazze S, Van de Laar FA, Fahey T. Diagnostic accuracy of the ID Migraine: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Headache. 2011;51(7):1140-8.

- Lipton RB. Chronic migraine, classification, differential diagnosis, and epidemiology. Headache. 2011;51 Suppl 2:77-83.

- Bendtsen L. Central sensitization in tension-type headache–possible pathophysiological mechanisms. Cephalalgia. 2000;20(5):486-508.

- Fumal A, Schoenen J. Tension-type headache: current research and clinical management. Lancet Neurol. 2008;7(1):70-83.

- Eller M, Goadsby PJ. MRI in headache. Expert Rev Neurother. 2013;13(3):263-73.

- Elliot S, Kernick D. Why do GPs with a special interest in headache investigate headache presentations with neuroradiology and what do they find? J Headache Pain. 2011;12(6):625-8.

- Wang HZ, Simonson TM, Greco WR, Yuh WT. Brain MR imaging in the evaluation of chronic headache in patients without other neurologic symptoms. Acad Radiol. 2001;8(5):405-8.

- Frishberg B, Rosenberg J, Matchar D, McCrory D, Pietrzak M, Rosen T, et al. Evidence-Based Guidelines in the Primary Care Setting: Neuroimaging in Patients with Nonacute Headache. Minneapolis: American Academy of Neurology; 2014.

- Mullally WJ, Hall KE. Value of Patient-Directed Brain Magnetic Resonance Imaging Scan with a Diagnosis of Migraine. Am J Med. 2018;131(4):438-41.

- Evans RW. Incidental Findings and Normal Anatomical Variants on MRI of the Brain in Adults for Primary Headaches. Headache. 2017;57(5):780-91.