The signs and symptoms of IBD vary dramatically, which can lead to delays in diagnosis, write Drs Farzan F. Bahin and Simmi Zahid

There is a high prevalence of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) in Australia, and due to improving therapies there are an increasing number of highly functioning patients being managed in the community. The role of the general practitioner is paramount in the coordination and ongoing monitoring of this chronic disease, while working closely with the gastroenterologist.

Inflammatory bowel disease is a complex disease to both diagnose and manage, posing a number of challenges to those involved in the care of the patient. We will briefly outline the modalities in diagnosis, updates in management and ancillary factors that contribute to the overall well-being of the patient with IBD.

PREVALANCE

It is estimated that approximately 75000 Australians are living with IBD, with over 1622 new cases diagnosed every year.1 Australia has among the highest reported incidence of IBD worldwide, posing a significant healthcare burden – hospital costs for 2012 were estimated to be more than $100 million a year.2

Crohn’s disease occurs equally in both males and females, whereas ulcerative colitis occurs 20 to 30% more in males than females.3

DIAGNOSIS

IBD can be diagnosed at any age, but has a peak prevalence in Australia among the 30 to 39-year-old otherwise healthy active people. The signs and symptoms vary dramatically among patients, often leading to a clinical predicament and delay in diagnosis.

In addition to diagnosis, stratifying patients earlier in the disease course is crucial in identifying high risk patients and therefore commencing early aggressive treatment, where indicated, to avoid later complications.

While there are many overlying pathological and radiological features of Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis, the main distinguishing feature is site of involvement, with Crohn’s disease potentially affecting any region from the mouth to anus.

Symptoms usually correlate with location and extent of inflammation, however often there is a discordance and investigations are required to qualify these objectively.4 Challenges arise when patients who seem clinically well are in fact concealing active inflammation, highlighting the importance of close and constant monitoring.

Patients with ulcerative colitis predominantly present with bloody diarrhoea, with associated abdominal pain, urgency or tenesmus. Symptoms of Crohn’s disease vary significantly given the potential diverse locations of involvement but are typically abdominal pain, diarrhoea and weight loss.

Systemic features such as fatigue, anorexia and fever are more common compared with ulcerative colitis, and can sometimes reflect underlying weight loss, nutritional deficiencies or malabsorption. Strictures, fistulae or abscesses are crucial to identify on history as these features often correlate with more severe disease.5

Delays in diagnosis often arise due to IBD sharing symptoms with other more common and less sinister conditions such as irritable bowel syndrome, gastroenteritis or functional disorders. Temporal and alarm features are important to recognise, and can be used in conjunction with investigations to best delineate the disease.

There are a number of standardised classification systems that can be utilised in clinical decision making.

Crohn’s disease

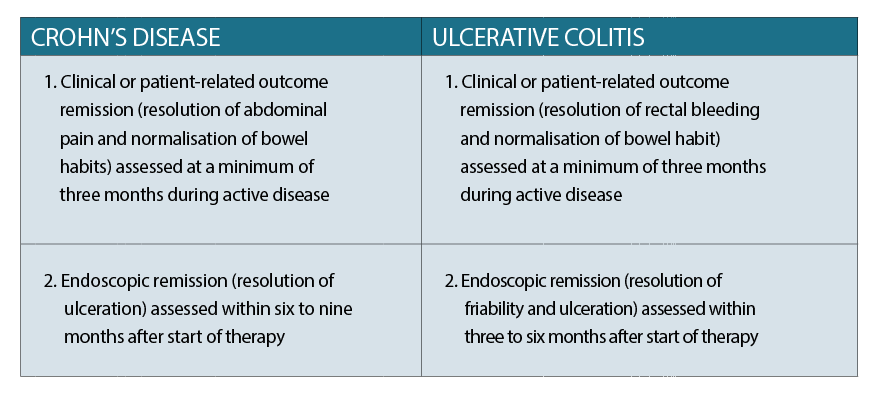

The Crohn’s Disease Activity Index (CDAI) is an estimate of the clinical severity of the disease, whereas disease phenotype (degree of inflammation) is classified according to the Montreal Classification.6 The goal of therapy with Crohn’s disease is to achieve a CDAI of < 150 for at least 12 months.

Ulcerative colitis

The European Crohn’s and Colitis Organisation (ECCO) and the American College of Gastroenterology classify UC using the Montreal Classification, based on Truelove and Witts’ criteria. The goal of therapy with ulcerative colitis is to achieve complete resolution of symptoms and endoscopic mucosal healing.

INVESTIGATIONS

There is unfortunately no one reliable test to diagnose IBD, but rather a concert of laboratory, imaging and endoscopic investigation. Simple laboratory tests can be done to evaluate the severity of inflammation and any associated deficiencies.

Blood examination

Basic investigations outlined below are helpful in ascertaining the presence and severity of disease, and are helpful to have done prior to referring to the gastroenterologist.

Full blood count: anaemia, elevated white cell count or platelets suggestive of inflammation.7

Inflammatory markers: elevated CRP and ESR.

Biochemistry: low albumin (inflammation and malnutrition), impaired renal function due to dehydration, electrolyte imbalances.

Faecal testing

Faecal calprotectin: most widely used neutrophil-derived protein biomarker. Highly sensitive, non-invasive marker of intestinal inflammation.8 It is utilised as a non-invasive marker of disease monitoring in patients on therapy for IBD, as well as in helping with diagnosis by excluding IBS. Limiting factors include potential for false positives, and that it is not yet MBS rebateable in Australia (costs the patient approximately $42).

Stool microscopy, culture and sensitivity: Clostridium difficile, or other bacterial, viral or parasitic organisms must be excluded when a patient presents with symptoms suggestive of IBD. Often in those with already established IBD, infectious gastroenteritis can, in fact, trigger an IBD flare or can occur concurrently. Furthermore, IBD patients on immunosuppression are more susceptible to infections and it is important to exclude these when they present with suggestive symptoms. C. difficile in particular has a higher incidence in patients with IBD, and is associated with higher mortality rates.9

Specialised testing

If there is a high suspicion for IBD after consultation with the GP and above investigations, then early specialist referral is encouraged in order to arrange for more specific and targeted investigations such as endoscopy and/or radiological tests. Once referred, the gastroenterologist will evaluate the urgency of further investigations and accordingly arrange for gastroscopy and/or colonoscopy/ileoscopy for biopsies and histological diagnosis. Where there is suspected small bowel involvement, they may also arrange for an MRI enterography or video capsule endoscopy. Perianal disease (abscesses or fistulae) is also further evaluated with MRI and generally warrant surgical involvement.3,4

Once a diagnosis of IBD has been established by the specialist after correlation with clinical, histological and imaging data, the disease is generally stratified and the best management strategy is identified.

MEDICAL MANAGEMENT

With the advent of new biologic agents, treatment targets expand beyond just resolution of clinical symptoms. The current paradigm of treatment in IBD is “Treat to Target” (T2T), where, if defined targets (clinical, biochemical or composite target) are not achieved, then treatment is either intensified or switched.11

As the treatment of IBD is very complex and individualistic, we will only briefly summarise when and which medications are used in Australia, and instead focus on the role of the GP in monitoring patients on these treatments and when to escalate their care.

Monitoring

Due to the significant side effect profile of medications, as well as the often indolent nature of the disease, IBD requires close biochemical monitoring, for which the GP plays a pivotal role. Furthermore, as the goals of therapy have now been maximised, there are greater expectations to optimise outcomes and minimise treatment failure.

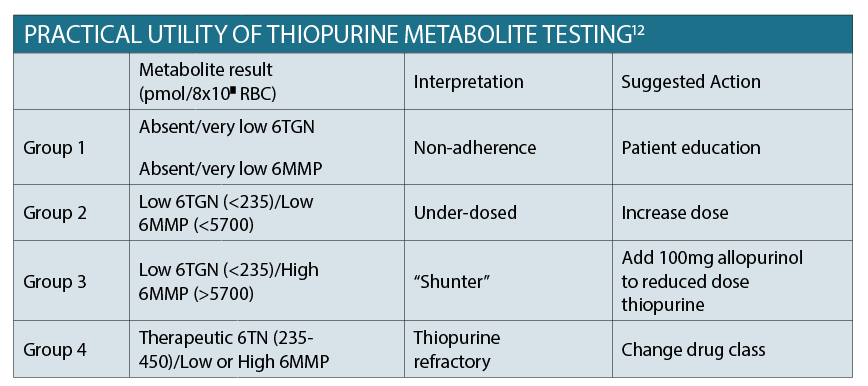

Thiopurine metabolite testing

Up to 50% of patients do not respond to thiopurine dosing, and up to 20% will experience one or more adverse effects. The table aboveoutlines the target 6TGN (associated with clinical efficacy) and 6MMP (associated with hepatotoxicity) results. In order to detect adverse events early, it is crucial to perform close monitoring of the patient’s blood biochemistry once commenced on treatment. This involves initially performing FBC, EUC and LFTs fortnightly for four weeks, monthly for four months, then every three to four months long term.12 The other advantage of testing metabolites is to identify patients who are non-adherent with therapy, which often only requires patient education in order to optimise outcomes.

Therapeutic drug monitoring

This is becoming increasingly common practice among gastroenterologists,and helps guide whether dose adjustment or class switching is required. It should only be performed and acted on by the gastroenterologist.

Faecal calprotectin

As discussed earlier, faecal calprotectin is quite a useful and non-invasive tool in monitoring the disease and response to therapy. It should not, however, replace clinical judgement but rather be integrated into the armamentarium utilised by gastroenterologists managing IBD.13

Managing flares

Early identification of a disease flare is crucial in preventing serious complications such as bowel obstruction or perforation. Often, most patients are well-attuned to their symptoms and know when they are having a flare.

Other times, it is the discretion of the medical practitioner to determine whether the patient will benefit from hospitalisation.

Some features in the history that would point to emergency referral would be severe abdominal pain and/or fevers with frequent bloody diarrhoea (for example more than six episodes/day), or inability to tolerate oral intake.

In such instances, patients benefit from emergent imaging and commencement of intravenous hydrocortisone.

For patients with increased stool frequency or tolerable abdominal pain, it would be appropriate to consider commencing them on prednisone 40mg daily orally and to inform their gastroenterologist in order to expedite follow up within the next week. Performing basic bloods tests, including inflammatory markers, can assist the specialist in deciding the next best step in management.

NON-PHARMACOLOGICAL MANAGEMENT

Probiotics: there are no robust studies supporting the use of probiotics in inducing remission, preventing relapses or post-operative recurrence of Crohn’s disease. There is some historical data suggesting that probiotics have shown to safely maintain remission in ulcerative colitis, or those with recurrent or refractory pouchitis. Current theory is that probiotics may have a role in treating gastrointestinal conditions, boosting immunity and preventing or slowing the development of certain types of cancer.

We can only assure patients that there is a lack of evidence-based guidelines and while probiotics use seems safe, we cannot conclude that they are a feasible alternative to pharmacological treatment.14 It needs to be reiterated to patients that they are by no means a substitute, but can be used as an adjunct should the patient choose to. Gastroenterologists do not routinely recommend the use of probiotics in IBD.

In a similar vein, there are only poor quality studies supporting the use of herbal and nutritional supplements. In fact some supplements, such as St John’s Wort, can interact with immunosuppressive agents and interfere with their efficacy.15

Diet: There are no strict rules with diet in IBD. Generally, we advise patients with Crohn’s disease to adhere to a low residue diet. There is no evidence that certain food groups trigger flares, although each individual may subjectively experience symptoms of gastrointestinal irritation with certain foods. In these scenarios, it is generally advised that the patient avoid that certain food but be reassured that it has not contributed to increased inflammation or worsened disease activity. Referral to a dietician is helpful for the patient in determining a diet that best suits them. In general, the aim is to avoid being malnourished.

HOLISTIC CARE

The management of IBD requires a multi-disciplinary approach with vigilant monitoring thereby anticipating and preventing complications in order to maximise patient outcome. GPs play a big role in early diagnosis, supporting the patient psychologically, as well as observing response and adherence to maintenance therapy. Given the life-long and complex nature of this disease, patients would certainly benefit from generating an action plan in conjunction with their gastroenterologist and GP in order to recognise problems early. Some important factors to consider from a preventative medicine perspective will be briefly outlined below.

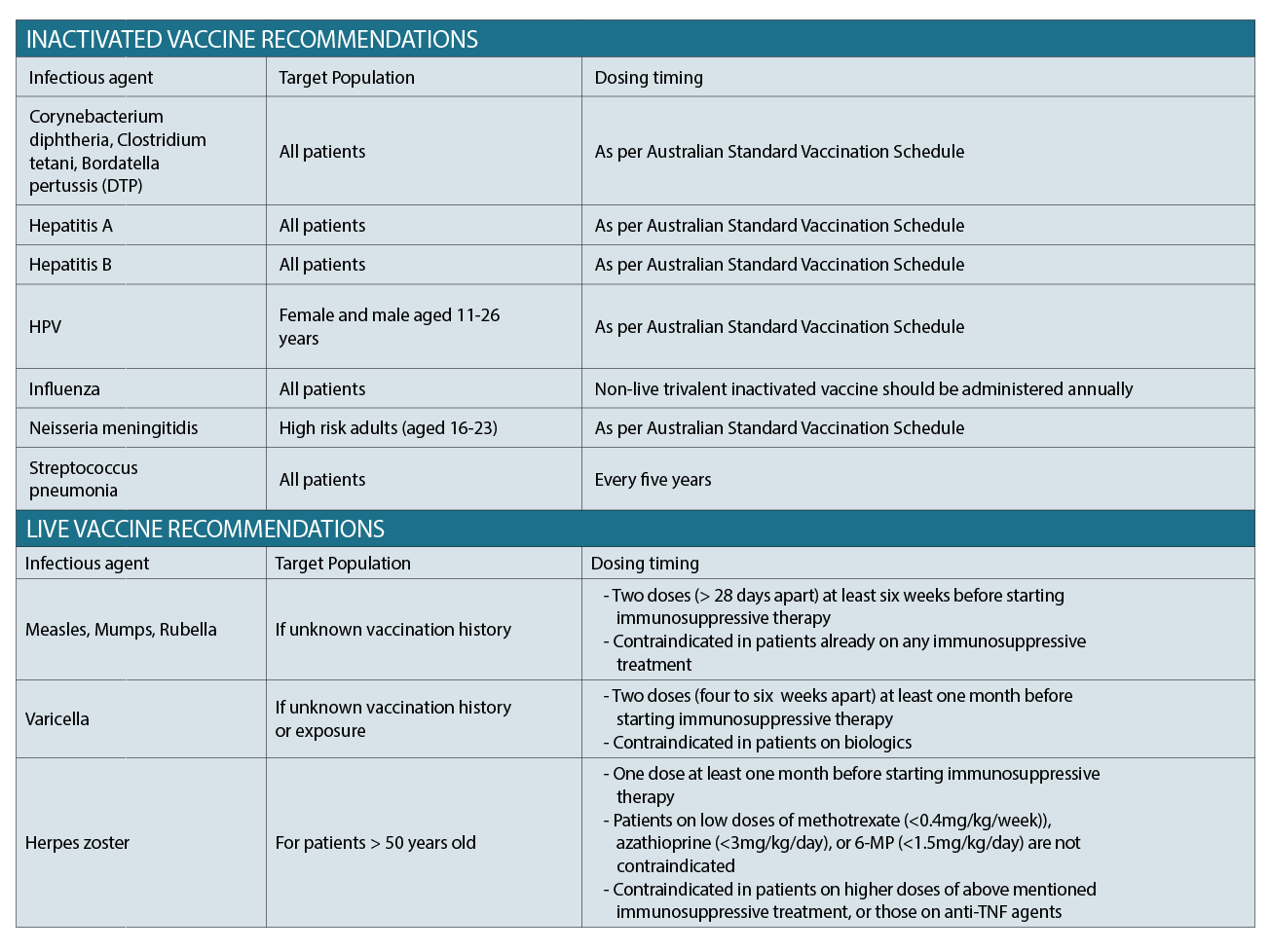

Vaccination

Vaccination recommendations should be guided by the gastroenterologist. Practice is currently based on recommendations, however, evidence-based data remains low. Several studies have, however, documented the poor uptake of routine vaccinations among patients with IBD, with common reasons being patient lack of awareness and fear of side effects. It is important that both the gastroenterologist and GP reinforce the importance of remaining up to date with their vaccination schedule, and reassuring them in particular that there is no evidence correlating increased disease activity post vaccination.16

The table above outlines common vaccinations, targeted patients, and appropriate timing of administration. In general, inactivated vaccines can be given to patients on immunosuppression (as per Australian Standard Vaccination Schedule), whereas live vaccines need to be timed with therapy.

Malignancy screening

Patients on chronic immunosuppression must be up-to-date with their routine national screening programs.

Of note, women with IBD on immunosuppressive therapy need to ensure their CST has been done.

A recently published meta-analysis found sufficient evidence to suggest an increased risk of cervical high-grade dysplasia and cancer in patients with IBD on immunosuppressive medications.17

Patients with IBD should undergo screening for melanoma independent of the use of biologic therapy, whereas those on immunomodulators (6-MP or azathioprine) should undergo screening for non-melanoma squamous cell cancer (NMSC) particularly over the age of 50. Overall, IBD was associated with a 37% increase in risk of melanoma compared to the general population (Singh et al 2014). There is a paucity of data regarding the evidence of NMSC in IBD patients, however in general those who are chronically immunosuppressed have an increased risk of SCCs and BCCs.18

Given these trends it is crucial that patients have at least annual skin surveillance and education regarding sun protection, including dermatology referral in those identified as higher risk.

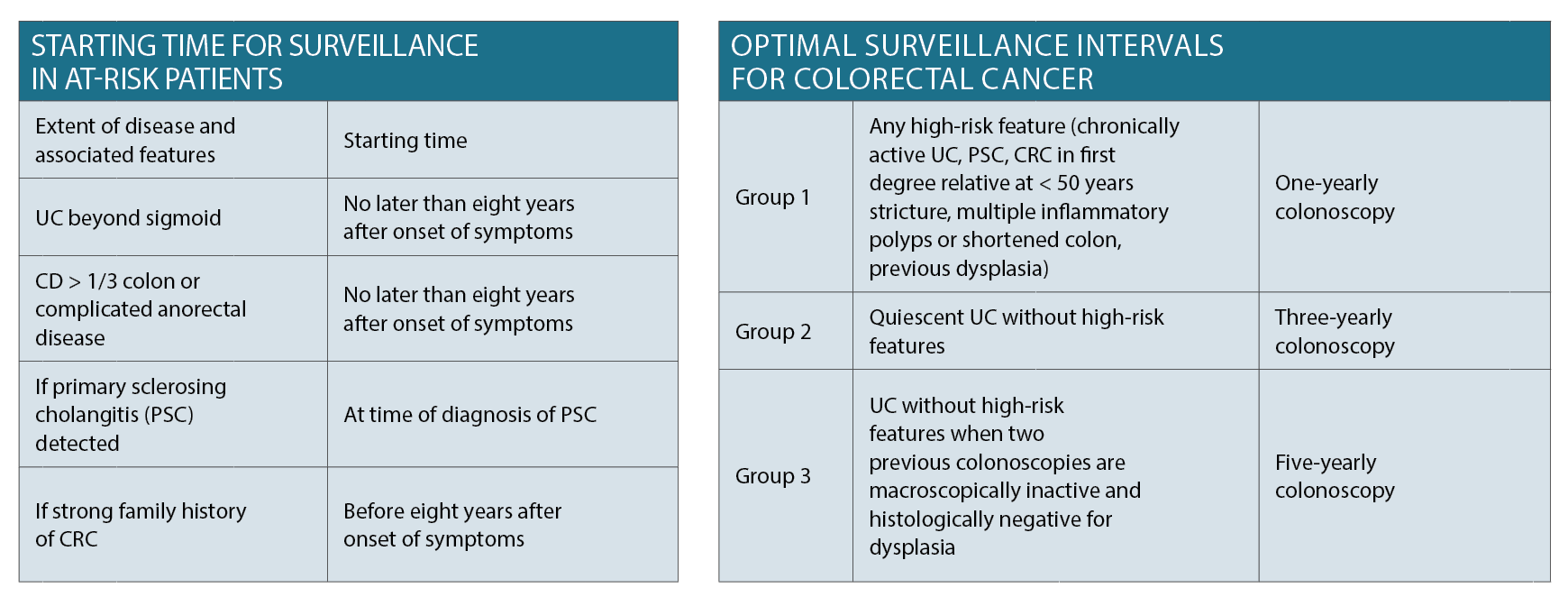

Different parameters arise for colorectal cancer (CRC) screening in patients with IBD as per the Gastroenterological Society of Australia (GESA) guidelines which have been summarised in the tables on page 28.

Iron deficiency/nutrition

For patients with mild disease or those in remission, this should be monitored every six months. Those with active disease should have iron stores and haemoglobin tested every three months. Serum folate and B12 should be measured annually.

Diagnostic criteria for iron deficiency varies for patients with IBD, as ferritin is influenced by the degree of inflammation. In patients without clinical, endoscopic or biochemical evidence of active disease, serum ferritin < 30 µg/L is appropriate criterion, whereas in the presence of inflammation a serum ferritin up to 100 µg/L may still be consistent with iron deficiency. Anaemia in IBD patients can often be a combination of iron deficiency and the chronic inflammatory state.8

For iron replacement therapy, intravenous iron should be considered as first line treatment if there is clinically active IBD. In Australia, this is available as Ferinject (ferric carboxymaltose) 500mg/10mL injection which can be administered by nursing staff. It currently costs the patient $39.50.19

Aside from replacement therapy, preventing iron and other nutritional deficiencies is important in the management of IBD. Early referral to a dietitian can assist in this process, thereby optimising patient nutrition and reserve.

Smoking

Smoking cessation is particularly pertinent in Crohn’s disease, where there is data to suggest that it is associated with disease development, progress, poor medical and surgical outcomes.20 Smoking also appears to adversely affect response to therapy, with some reports showing that 22% of smokers vs 74% of non-smokers responded to infliximab.21 Repeated counselling referral to smoking-cessation programs both the GP and gastroenterologists can assist in smoking cessation and should be addressed at every visit.

Osteoporosis

It has been estimated that 14 to 24% of patients with IBD have osteoporosis.22 The pathogenesis remains incompletely understood and likely multifactorial, owing to a combination of steroid treatment, systemic effects of chronic inflammation, calcium and vitamin D deficiencies as well as malnutrition. There is no current data supporting routine BMD assessment in IBD patients due to a low absolute risk of bone fractures. Subsequently a more conservative and cost effective approach would be to follow established guidelines for the general population (i.e. screening all patients with a pre-existing fragility fracture, women aged 65 and men aged 70 and older).

A lower threshold, however, should be maintained in patients who have been on steroid therapy or are about to start. Management in general involves calcium and vitamin D replacement in those with established osteopaenia or those at high risk (more than three months of corticosteroids, post-menopausal females or males > 50, or previous fragility fractures).

Psychological well-being

Anxiety and depression has not been shown to have any direct correlation with disease activity, however it certainly plays a role in treatment adherence and patient perspective which can subsequently impact disease trajectory. A systematic review found that anxiety was present in 19% of IBD patients vs 9.6% of the background population, and depression found in 21.2% vs 13.4%. There was just as much depression in those with inactive disease as those with active.23

In another Canadian study, researcers demonstrated that the interaction of perceived stress and avoidance coping were predictors of earlier relapse.24 Evidently, screening patients for mood disorders and offering early intervention can improve patient outcomes as well as overall quality of life.

Pregnancy and lactation

As per the ECCO guidelines, there is no evidence that ulcerative colitis or inactive Crohn’s disease affects fertility. The same applies for medications in females, while sulfasalazine causes reversible oligospermia. Pregnancy may influence the course of IBD, and it has been shown that conception at the time of active disease increases the risk of activity during pregnancy. This requires close coordination between the obstetrician and GP.

Dr Farzan F. Bahin, FRACP, PhD, Mphil, is Consultant Physician and Interventional Gastroenterologist, Visiting Medical Officer, Blacktown and Mt Druitt Hospitals. He is also Clinical Lecturer, University of Sydney and Western Sydney University.

Dr Simmi Zahid is an Advanced Trainee, Westmead and Blacktown Hospital

References:

1. Wilson J, Hair C, Knight R, et al. High incidence of inflammatory bowel disease in Australia: a prospective population-based Australian incidence study. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2010; 16(9): 1550-6

2. Economics Access. The economic costs of Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis. In: Australia Cac, (ed.). Melbourne, Australia 2007

3. Bernstein. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101(7):1559-68

4.Gomollon F, Dignass A, Annese V, et al. 3rd European Evidence-based Consensus on the Diagnosis and Management of Crohn’s Disease 2016: Part 1: Diagnosis and Medical Management. Journal of Crohn’s and Colitis 2016; 11(1): 3-25

5. Magro F, Gionchetti P, Eliakim R, et al. Third European Evidence-based Consensus on Diagnosis and Management of Ulcerative Colitis. Part 1: Definitions, Diagnosis, Extra-intestinal Manifestations, Pregnancy, Cancer Surveillance, Surgery, and Ileo-anal Pouch Disorders. Journal of Crohn’s and Colitis 2017; 11(6): 649-70

6. Mowat C, Cole A, Windsor A, et al. Guidelines for the management of inflammatory bowel disease in adults. Gut. 2011;60(5):571–607.

7. Satsangi J, Silverberg MS, Vermiere S, Colombel J-F. The Montreal classification of inflammatory bowel disease: controversies, consensus, and implications. 2006. P. 749-53

8. Dignass AIK, Basche C, Bettenworth D, et al. European consensus on the diagnosis and management of iron deficiency and anaemia in inflammatory bowel diseases. J Crohn Colitis 2015; 9(3):211-22

9. Andersen V, Whorwell P, Fortea J, Auziere S. An exploration of the barriers to the confident diagnosis of irritable bowel syndrome. A survey among general practioners, gastroenterologists and experts in five European countries. United European Gastroenterology Journal 2015; 3(1): 39-52

10. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2011;8:17

11. Peyrin-Biroulet L et al. Selecting therapeutic targets in inflammatory bowel disease (STRIDE) determining therapeutic goals for treat-to-target. Am J Gastroenterol. 2015;110(9):1324-38.

12. Dubinsky MC, Lamothe S, Yang HY, et al. Pharmacogenomics and metabolite measurement for 6-mercaptopurine therapy in inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology 2000; 118(4): 705-13

13. D’Haens G, Ferrante M, Vermeire S, et al. Fecal calprotectin is a surrogate marker for endoscopic lesions in inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2012;18(12):2218–24.

14. Derwa Y, Gracie DJ, Hamlin PJ, Ford AC. Systematic review with meta-analysis: the efficacy of probiotics in inflammatory bowel disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2017; 46(4): 389-400

15. Cheifetz AS, Gianotti R, Luber R, Gibson PR. Complementary and Alternative Medicines Used by Patient with Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Gastroenterology 2017; 152(2): 415-5

16. Sands BE, Cuffari C, Katz J et al. Guidelines for immunisations in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2004; 10:677-92

17. Allegretti JR, Barnes EL, Cameron A. Are patients with inflammatory bowel disease on chronic immunosuppressive therapy at increased risk of cervical high-grade dysplasia/cancer? A meta-analysis. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2015;21:1089–1097.

18. Silverberg MJ, Leyden W, Warton EM et al. HIV infection status, immunodeficiency, and the incidence of non-melanoma skin cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst 2013;105:350–360.

19. Gasche C, Berstad A, Befritis R, et al. Guidelines on the diagnosis and management of iron deficiency and anaemia in inflammatory bowel diseases. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2007; 13(12):1545-53

20. Somerville KW, Logan RF, Edmond M et al. Smoking and Crohn’s disease. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 1984;289:954–956.

21. Parsi MA, Achkar JP, Richardson S et al. Predictors of response to infliximab in patients with Crohn’s disease. Gastroenterology 2002;123:707–713.

22. Abitbol V, Roux C, Chaussade S et al. Metabolic bone assessment in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology 1995;108:417–422.

23. Mikocka-Walus AA, Turnbull DA, Moulding NT et al. Does psychological status influence clinical outcomes in patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) and other chronic gastroenterological diseases: an observational cohort prospective study. Biopsychosoc Med 2008;2:11.

24. Ananthakrishnan AN, Gainer VS, Cai T et al. Similar risk of depression and anxiety following surgery or hospitalization for Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis. Am J Gastroenterol 2013;108:594–601.